“… Without a sense of identity, there can be no real struggle…”

― Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed

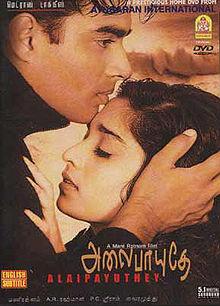

Like so many Tamil teens growing up in Scarborough (the burbs of Toronto, saturated with Tamil convenience stores, bakeries, banquet halls and known by the moniker of Little Jaffna), the search for my cultural identity began in high school and was set to the romantic soundtrack and cinematography of Kollywood. South Indian movies and soaps were ubiquitous in our home and the drama of teenage life seemed completely normal within the romance and theatrics of Kollywood cinema. I memorized Tamil film song lyrics religiously, and fell in love with the Vikrams and Suriyas and Maddys of the silver screen on rotation.

And yet, I became fascinated with the conflict in Sri Lanka. What started it? Why had it raged on for so many years? The more I dived into the history, the more I spoke to peers, and the more I read news stories outlining the latest horror, the more I became angry. History, I soon realized, was not an objective re-telling of events. To the victors not only go the spoils but the privilege of (re)writing the narrative and framing it as fact. I began to truly understand the meaning of propaganda and the power of spin and began to feel the burden of a mind occupied by half-truths and whole lies. I wasn’t interested in the official party line anymore. I turned instead to the masses and to my surprise, the masses were extremely organized.

The Tamil community in Toronto is the largest diaspora community of Sri Lankan Tamils outside of Asia. The most recent Canadian census data shows that Tamils make up 5.7% of the Toronto population and boast the 5th most spoken non-official language in the city. Toronto’s Tamil community has been praised by other minority groups for its ability to mobilize and advocate as a community, to stand strong, and demand justice with a unified voice. And this is what I found when I sought an outlet for my anger, and a means to rectify the powerlessness I felt in the face of the injustices that were taking place in Sri Lanka.

Maybe you could chalk it up to the untainted ideology of youth, or perhaps to the misguided belief that our voices mattered more than geopolitical forces. Perhaps we could not face the stark reality that Sri Lanka lacked any secret trove of oil to whet the appetites of superpowers. Regardless, after the breakdown of the ceasefire in 2006 and the escalation of conflict over 2008 and 2009, we took to the streets in the thousands, with our megaphones and homemade signs, and pleaded with the “international community” to intervene in this genocide.

We began with two large human chains; thousands of people holding hands with strangers, stretching up and down the downtown core. We stood on sidewalks, politely making way for those passing by. Some stopped to say how beautiful this effort was. Others stomped along annoyed by the inconvenience.

When these efforts fell on deaf ears, we marched on Parliament Hill in the nation’s capital. We loaded buses full of people from Toronto and Montreal and sent them off to Ottawa. Some slept over in make-shift tents, others made the trek back and forth each day. We protested peacefully for three weeks non-stop and despite protestors coming out in the tens of thousands, there was never any violence or property damage. Certainly streets were blocked, buses diverted and police officers paid overtime to stand watch over this gathering, but when families come out to protest together, from children to parents to grandparents, the safety of the community becomes paramount. We had volunteers directing traffic, distributing hot tea, and collecting any fly away garbage. We took turns leading chants until our voices were hoarse. We waved the Canadian flag alongside the national flag of Tamil Eelam. We spoke to the media. And most importantly, we shared our own stories among the beats of the drum circles that emerged. I think, for the first time in many years, we were open to our own narrative, free to share the stories of grief, loss, and sorrow that had been carried along in silence for so many years. We mourned as a community, but we also became stronger.

But while many stood in solidarity with us, the overarching rhetoric of the “average Canadian” was “go back to where you came from!” In a few weeks, the 20 odd years of my citizenship in this country were erased and I was overtly otherized. Suddenly, the comments were focused not on the genocide taking place in Sri Lanka, but on how Tamil people protest in Toronto so they can take the public transit home and buy groceries along the way. We were an annoyance now, no longer the quiet model minority that we had built our reputation around. Yes, we were still factory labourers, and line cooks, and doctors, and engineers, but now suddenly, we had a voice too; a voice that articulated well-reasoned and emphatic political demands. But it was a voice that fell on deaf ears, or rather was selectively ignored by those who felt that Canada needed to be protected from the battle scars carried with asylum seekers as we fled. They told us to let go and move on, to assimilate and be grateful. Because this was Canada, a land of multiculturalism, where no single immigrant narrative matters more than the other. And yet every November 11th, we gather together as Canadians and recite the all-important words “Lest we forget.” Because their heroes are more noble than ours, their losses more significant.

After weeks and months of protests and with nothing but empty words from pandering politicians, when I woke up on Mother’s Day morning of ‘09 to have my phone inundated with messages and news of chemical bombs being unleashed on civilians in safe zones, despite growing frustration, there was nothing we could do but take to the streets. I didn’t know when I woke up that morning that I would end my day as part of a human blockade on the Gardiner Expressway in Toronto, but being a part of that day has been a defining moment in the evolving landscape of my identity, shaping the way I see myself and the way I see my place within this place that I call home.