DailyMail: Every night of the five years she spent in prison for murder, Frances Inglis went to sleep thinking of her son Tom and the 22 years they shared before she ended his life. She remembered the strong, handsome young man he was, blessed with a mischievous sense of humor and zest for life – and the pitiful state to which he was reduced.

In the small hours, as she tossed and turned, the nightmare vision of Tom lying permanently brain‑damaged in a hospital bed with no hope of recovery returned to haunt her. She wept inconsolably as she recalled the image of her son’s once‑perfect face horribly deformed by the emergency surgery that saved his life after a freak accident left him with catastrophic head injuries.

Tom’s swollen tongue protruded from cracked lips, his limbs were contorted and his eyes open but unseeing. There was a large dent where his skull had been removed to relieve brain pressure. Doubly incontinent and unable to communicate, Tom was in a vegetative state. He would need 24-hour care for the rest of his life.

‘Seeing my darling son like that was pure hell,’ says Frances, her voice breaking. ‘It was like watching someone you love being captured, held to ransom and tortured every single day. It was horror, nothing but endless horror.’

‘So in prison, whenever I asked myself: “Did I do the right thing?” I made myself think of Tom in that terrible state, alive but with no life to speak of, and I felt at peace that I was able to release him from his suffering.’

Frances, 61, loved Tom with all her heart. She gave him life. But it was she who – in a desperate and shocking act – ended it, convinced it was what her son would have wanted.

This respectable, upstanding wife and mother-of-three, who had devoted her life to working with adults and children with learning and physical disabilities, killed Tom by injecting him with street heroin, bought for £200 from a dealer in London’s King’s Cross.

In her mind it was a ‘mercy killing’. But in the eyes of the law it was murder, and in January 2010 Frances Inglis was found guilty by majority verdict and sentenced to life, with a recommendation she serve at least nine years (reduced to five on appeal).

Last week she was released on license (having been on remand since 2008 before her conviction), and this is her first interview about the heartbreaking case that not only made headlines but divided public opinion.

Fragile and still clearly grief-stricken, she says she has only one regret: that she didn’t succeed in ending Tom’s life sooner. Keeping him alive, she insists, was ‘inhumane’. To allow Tom to die by consenting to the withdrawal of food and hydration would have been, in her mind, ‘a cruel torture’.

She is only speaking out now because she believes the law needs urgent review. How can it be, she asks, that she was treated more harshly than other killers driven by baser emotions?

So were these the compassionate actions of a loving mother – or, as prosecutors successfully argued, the criminal act of a woman deranged by grief, projecting her own suffering on to a young man unable to express his own wishes?

For this, as the High Court pointed out when they refused her appeal against conviction in November 2010, was not an assisted suicide. Tom was incapable of communicating or deciding whether he wanted to live or die.

It is enshrined in law that all life is sacred and the most vulnerable members of society deserve the same level of protection as everyone else.

Tom’s death was premeditated and planned rather than the result of a momentary loss of control. ‘I gave my son a merciful death,’ says Frances. ‘I knew what I was doing was wrong in the eyes of the law; it felt right for my son.

‘I couldn’t bear for him to continue like that, and I know he wouldn’t have wanted to be kept alive in that condition.

‘Tom was a physically fit and healthy young man. He could have lived for another 40 years lying in a bed in that vegetative state. I would have done anything and accepted any punishment to release him from that suffering and to see my son at peace.

‘It wasn’t done in anger, it was done with compassion and love, and to this day I don’t regard what I did as murder.

‘All I wanted was for Tom to have a painless death. He passed away peacefully in my arms. The last words he heard were from me, his mother, telling him that I loved him.

‘Medical staff could have applied to the courts to allow Tom to die by withdrawing food and hydration, but to me that would have been unbearably cruel. It could have taken him weeks to pass away, suffering from hunger and thirst. We treat injured animals better than that.

‘If Tom had been left with some quality of life, I would have supported keeping him alive 100 per cent because the care he was receiving from nurses was wonderful.’

‘I’ve worked with people with learning and physical disabilities and there can be a lovely quality of life. But there are different degrees, and Tom’s disability was profound.’

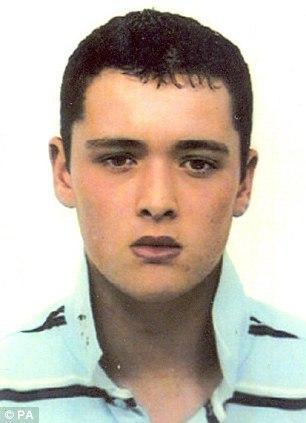

It was in July 2007 that Tom Inglis, a pipe-fitter from Essex, suffered catastrophic head injuries after jumping from a moving ambulance. He was being taken to hospital having suffered a split lip and concussion when he tried to break up a fight outside a pub in Dagenham, Essex.

Tom, then aged 21, didn’t want to go to hospital, but was told by paramedics he had no choice given the extent of his initial injuries. Disorientated and agitated after his concussion, Tom – who wasn’t drunk – opened the ambulance doors and leapt out while it was traveling at 30mph.

The London Ambulance Service has since ordered a review of its fleet’s door-locking mechanisms to prevent such an incident from happening again.

Surgeons at Queen’s Hospital, Romford, carried out an emergency decompressive craniectomy to remove part of Tom’s skull – almost his entire forehead – to relieve pressure on his swelling brain.

Despite one consultant telling Frances, her former partner Alex, 72, and their two other sons Alex Jnr, 31, and Michael 26, there was no reason why Tom shouldn’t make a good recovery, other doctors warned he could be left with severe disabilities. This, tragically, is what happened.

To this day, Frances remains distraught that surgeons carried out this controversial procedure instead of letting nature take its course. Medical trials suggest that the risks of the operation in adults may outweigh the potential benefits in terms of quality of life.

‘Some people believe that life should be saved at any cost, but I don’t. I begged medical staff not to perform the operation. I was told: “He’ll die without it,” and I said: “Please don’t do it, I will allow him to die,”‘ sobs Frances, recalling her first sight of Tom after the operation. ‘We didn’t know what to expect, but I had a feeling it was going to be bad. It was so shocking that his girlfriend Danielle was physically sick.’

‘Tom’s face was so swollen, and there were tubes, drips and bandages covering where they’d taken away his skull. He was unconscious and I held Tom’s hand, telling him: “Don’t worry, darling, everything’s going to be fine. You’re going to walk out of here. Don’t give up.”

‘I think I was trying to convince myself as much as him. I didn’t even know if he could hear me.’ Three days later Tom underwent a second operation to relieve pressure at the back of the head near the brain stem. A week later Tom was brought out of his coma.

‘He was sweating terribly, his pulse rate was sky-high and his legs were thrashing around,’ says Frances, ‘but the worst thing was the look of terror in his eyes. The doctors and nurses kept telling me that we were seeing things that just weren’t there. They kept insisting he felt no pain and wasn’t aware, but nothing they said could convince me.’

After another medical assessment suggested Tom had suffered irreversible brain damage, Frances was beside herself. She now wishes surgeons had never operated on Tom, given the quality of life her son was left with.

‘One day an occupational therapist turned up at Tom’s bed with a mirror and comb,’ weeps Frances. ‘He said he’d come to teach my son how to shave and comb his hair. He was shocked at the sight of him and asked: “Has he deteriorated?” ’

‘We said: “No, he’s always been like this.” Tom couldn’t even swallow let alone shave. He couldn’t communicate at all, even through blinking.’

Frances, who at the time was re‑training as a nurse, first tried to kill Tom in September 2007. She did not tell Alex, from whom she’d separated before Tom’s injury, or their two other sons what she was planning. At that time, they still clung to the hope that he might recover against all the odds.

‘I wanted Tom’s death to be painless, peaceful and quick,’ says Frances. ‘I researched on the internet and thought that with heroin he would float away. I thought it would be a kind death.’

‘I didn’t know where to get it from, so I hung around needle exchanges asking people coming out where I could buy heroin. But they were suspicious of me and must have thought I was an undercover police officer.’

‘In the end I went to King’s Cross in London and asked people who looked like they were dealers if they knew where I could buy heroin. It wasn’t easy and took quite a long time before someone, in the end, said: “How much do you want?”

‘All the time I was thinking: “What am I doing?” But when I thought of Tom’s terrible suffering, I knew I had to go through with it for his sake.’

‘Injecting heroin into my own son was the worst thing I’ve ever had to do, but I did it because the thought of walking out and leaving him in that condition was unbearable to me.’

Frances stayed with Tom while he drifted into unconsciousness, whispering into his ear: ‘Everything will be fine.’ She left his room thinking he was dead. But once she’d gone, he suffered a cardiac arrest.

The medical team, responding to monitor alarms, resuscitated him, but Tom was left with even more profound disabilities as a result. ‘I was in a terrible state when I found out they’d brought him back to life. Why couldn’t he have been left at rest?’ asks Frances, who was arrested two weeks later on suspicion of attempted murder when tests revealed the heroin in his body.

‘When the police questioned me I denied everything. I wanted to tell the truth, but I knew that if I did, I would never get the chance to release Tom. I think they knew I’d done it, but there was no proof.’

Frances was released on bail on condition she did not see her son. She says the 14 months when she was prevented from visiting him in hospital were “pure hell”, thinking about what he must be enduring.

When Tom was transferred to a rehabilitation unit in Hertfordshire in the spring of 2008, Frances became tormented by the thought that medical staff might, if he deteriorated further, seek to apply to the High Court to let her son die by withdrawing food and hydration.

So in November that year she secretly visited Tom, pretending to be his aunt, knowing the staff there wouldn’t recognize her. Armed with another syringe filled with street heroin, she injected her adored son. This time she was successful.

‘I was terrified, absolutely terrified that I would be stopped and that they would resuscitate him again. I couldn’t live with that, or for Tom to continue living with this awful suffering,’ says Frances.’

‘The door to his room had to stay open at all times, so I had to pretend to act naturally for the 15 minutes we were alone together. As Tom was dying, a nurse came in to give him some medication. I ushered her out telling her to leave it till later.’

‘Then I closed the door, super-glued the lock and barricaded myself in to stop them from resuscitating Tom. I told them to call the police. I was panicked and anxious, but the moment Tom passed it felt like a burden had lifted. It was such a relief to know that he was at peace.’

Today, after five years in prison, Frances is slowly adjusting to normal life again. Her former partner and sons have supported her throughout and now, too, believe she did the right thing for Tom and should not have been punished with a prison term.

‘I grieve for Tom every day, but I don’t see myself as a murderer,’ says Frances, who compares herself to a soldier who compassionately puts a fallen comrade out of his misery on the battlefield rather than let him suffer.

‘Tom’s at peace now, and that’s all that really matters to me.’

DCG