I was folding away some laundry the other day when I noticed a hole in my J. Crew sweatshirt. It's about the size of my pinky nail, but threatens to get bigger, and it's located in the very inconvenient place of my sweatshirt's collar band. "I should mend that," I thought, until I realized I don't know how to mend anything at all.

The idea of mending today feels more like a promise than a reality. Alden Wicker touched on this last month in her Vox article about how the spare button represents all the ways we fail to be good consumers. Everyone has a stash of spare buttons rattling around in some drawer, with each button still neatly tucked inside its original packaging until we gather the will to throw it away. We buy things because they're supposedly "investment pieces" and "classics," but when it comes time to actually take care of our clothes, we don't actually know how - or, more often, can't be bothered.

"Really, the button fix is the easiest sewing project you could possibly do," Wicker wrote. "There's evidence of where the old button was located, and the holes of the new button guide your needle, while the button itself hides any sloppy work or loose threads. As long as you pick a pattern - crisscross or parallel stitches - and pull the thread tight, you literally cannot mess this up. And yet even this home ec 101 activity seems too much to ask of me and many people my age. [...] Maybe spare buttons are just aspirational, designed to make us believe something about ourselves that's not really true anymore. That we can have a fulfilling job and do crafty things in our spare time. That we could be satisfied with a capsule wardrobe of 30 items, which would free up so much time and psychic space that we would finally write that novel. That we could go plastic-free if we just put in a little more effort."

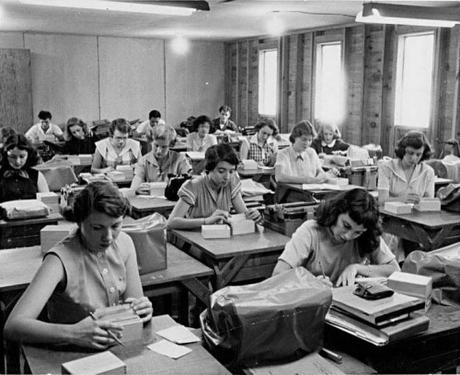

There was once a time when every American child was formally taught the basics of living. No girl graduated high school without knowing how to bake, budget, and sew, while her male counterpart took classes in autoshop and woodworking. On the domestic side, this type of education was formalized into the field of home economics sometime in the 19th century, partly to legitimize the housework that women were already performing. In her essay "Beyond Gender," Patricia Thompson wrote: "While the early curricula in the schools focused on such then-essential household tasks as cooking and sewing, the tasks were sustained by knowledge of science, human relations, aesthetics, and ethics. Home economics aimed to provide the learning needed for 'right living.'"

This all changed in the 1960s. For good reasons, second-wave feminists fought back against the rigid gender stereotypes of the previous decade and felt that mandatory home economic classes were pushing women into the confinement of housewifery (Gloria Steinem called this type of education a "cultural ghetto" in a Washington Post op-ed). Around the same time, the US government pulled federal funding that had been previously earmarked for these types of classes for decades. If schools wanted to keep their home economics programs, they had to fund them through a larger pool of money reserved for "vocational education."

The two biggest blows came in the 1990s. The first was the shift in the US economy from manufacturing to knowledge-intensive services (a shift that has been in the making for a long time, but came to a head during the information technology revolution). Today, secondary and post-secondary education are mostly aimed at teaching students how to read, write, and think critically for the modern economy, not how to manage household chores that can either be done by looking up something on the internet or simply outsourcing the work to a professional (e.g. tailors, maids, and cleaners).

The second blow came with the advent of fast fashion, which has made sewing and mending all but pointless. A hundred years ago, men wore detachable collars because the shirts themselves were so expensive. Now, whenever something rips or frays, buyers shrug and replace it with something new. When a shirt can be as cheap as $10, who has the time or inclination to send the item out to a professional or repair it themselves?

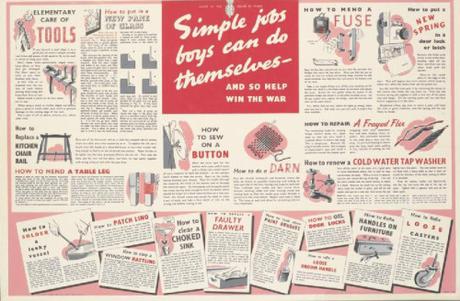

While home economics has mostly been in the purview of women, men everywhere have also needed to learn how to sew. In Britain, for example, the outbreak of the Second World War put a strain on domestic production and limited imports. As such, the government had to reallocate precious resources towards the war effort, but also ensure that each citizen had what they needed to survive.

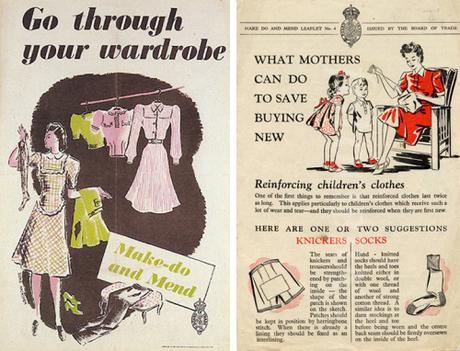

This resulted in some interesting changes. To save on materials, men's jackets were typically made with just three buttons and two pockets; pants were flat fronted and made with plain hems. Similarly, women's dresses were made without any pleats, elastic waistbands, or decorative belt detailing; their heel height was limited to two inches. The government around this time also had to limit clothing consumption, so they gave every citizen a certain number of "clothing coupons." To purchase clothes, British citizens would go into shops and pay for an item using the requisite number of tickets. Generally speaking, each adult was given enough tickets to purchase one new outfit per year.

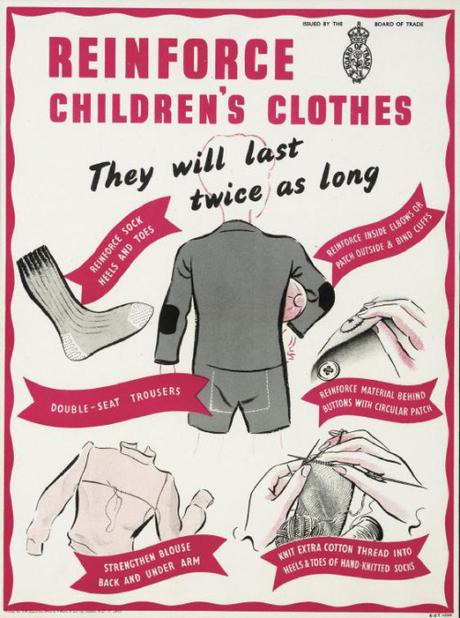

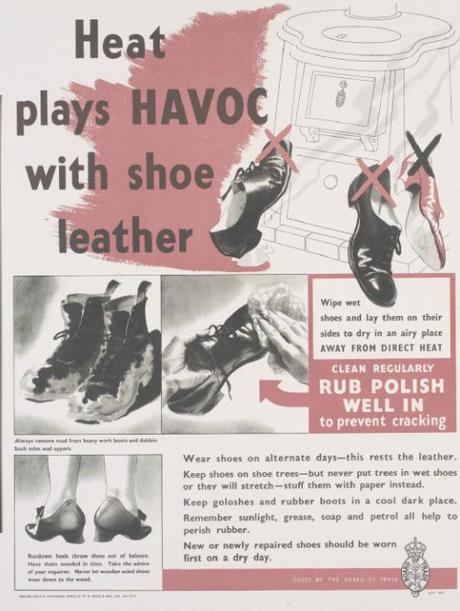

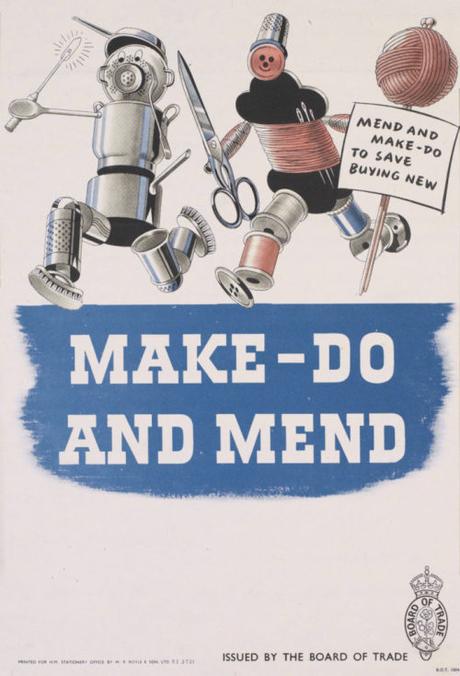

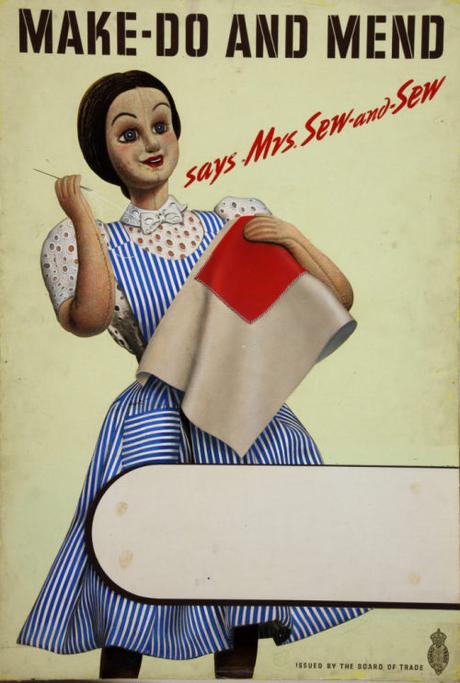

Out of this came a British "make-do and mend" ethos, whereby civilians were encouraged to patch up and repair old garments, rather than buy new and replace. When garments couldn't be patched up any longer, they were "deconstructed" so that their raw materials could be recycled. Raggedy sweaters, for example, were sometimes "unknitted" so that the yarns could be used to darn old knits or makes new ones entirely. The Ministry of Supply even organized a fashion show to demonstrate how new clothes could be made from old garments.

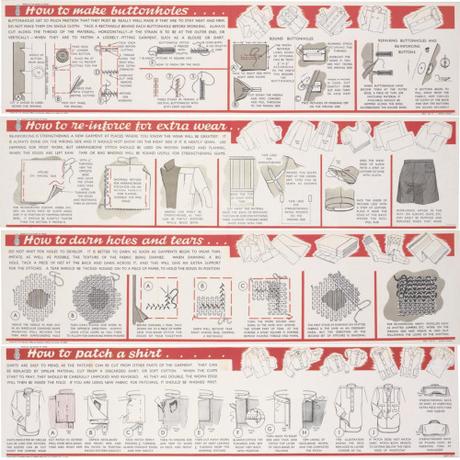

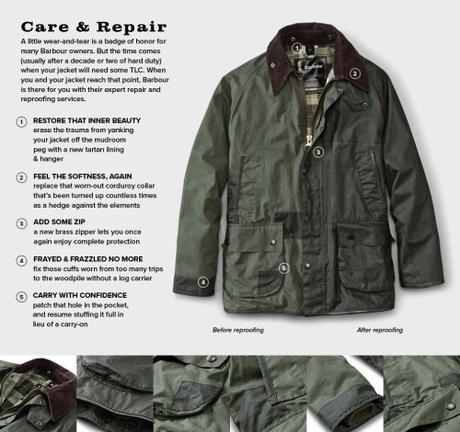

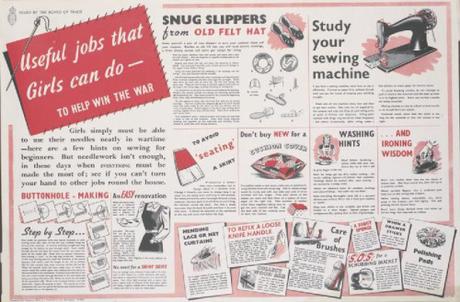

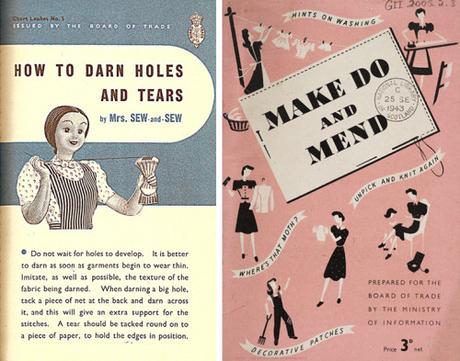

Women weren't the only people mending during this period; British soldiers and men back home were also encouraged to fix their clothes. In some of the "Make Do and Mend" ad campaigns, the government specifically targeted men. Pictured above are some of my favorite war-time tutorials on how to make buttonholes, reinforce areas for extra wear, darn holes, and patch shirts.

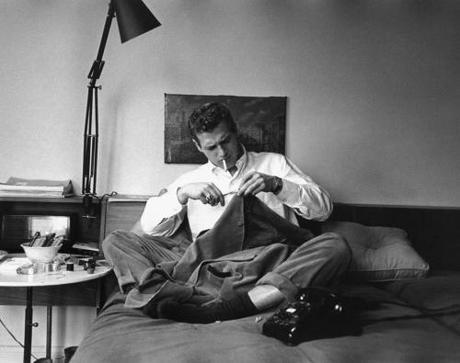

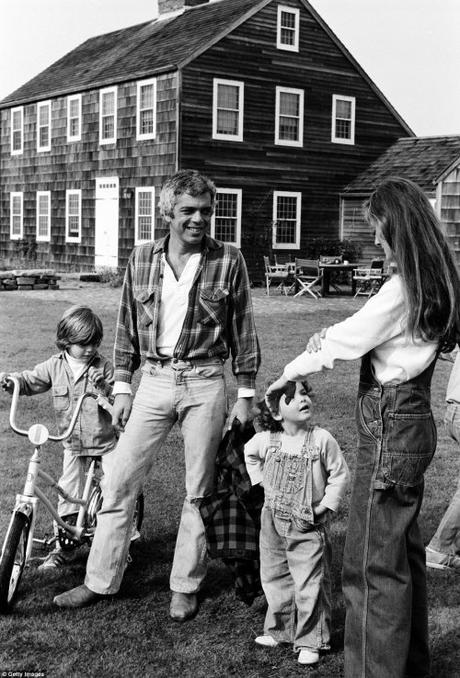

Like old friends and familiar places, old clothes bring a special kind of comfort that only time can reliably provide. Last fall, Ralph Lauren gave a rare interview on CBS Sunday Morning, where he talked about his career and how he's been able to stay relevant so long in an industry that reinvents itself every season. The best thing about the interview was his outfit. He wore a pair of light-washed blue jeans, some brown suede roper boots, a neatly tucked henley, and an unbuttoned, green flannel shirt.

It's the same outfit that he wore to a photo shoot in 1977, which was taken for a magazine story about his then-rising career. Forty-two years later, he wore the same old flannel, looking as cool as ever, on CBS. And if you assumed the shirt is from his own line, you'd be wrong. RRL, his company's workwear-inspired subline, didn't even debut until sixteen years after this photo shoot. No, the flannel is actually something Lauren originally bought from K-Mart, of all places.

"This is living proof of what I believe in," Lauren said of his slubby old flannel. "I love the aging of it, I love the rips, I love it all. I happen to like this because it's one that I have memories of. [I wore it today] because I wanted to look great."

The idea that clothes become more personal with time is hardly new. Rowen Pelling wrote something for The Telegraph a few years ago about this same subject:

My husband has a couple of old tweed jackets that he doesn't wear, so much as retreat to for sanctuary. They are so softened by use that they've become wool versions of those comfy, armchairs you find in old-fashioned men's clubs. I've lost count of the times they've been taken to a tailor for elbow patches, new linings and reinforced pockets. You could buy a fine new jacket several times over for the cost of the repairs, but that's irrelevant to these garments' owner. He returns to them for comfort and what a fashion editor might call "timeless style." They are protective, talismanic even.

I am endlessly touched by men's sentimental attachment to old clothes: Shetland jumpers that are more hole than whole, Panama hats missing half the crown, shirts with collars so frayed you can plait the edges. One barrister friend, who's just turned 50, has been wearing the same leather jacket since his student days. No matter that, nowadays, he's more Sid James than James Dean.

Without knowing how to mend, however, most of us will likely ever only know an old jacket or a pair of shoes. Finer garments, such as merino knits and woven shirts, are typically thrown away at the sight of their first hole. In an essay on what we lost when we forgot how to sew, Catie Nienaber wrote: "As this unique skill set has faded, so has our personal connection to clothing. Instinct has us reaching or our wallets rather than our needles. [...] Although North American home econ classes are still woefully underfunded and understaffed, young people are once again interested in making their own clothes. Perhaps the biggest difference between home economics and the DIY revival is that the former was seen as a duty and the latter is, for the most part, a choice. But from beginning-to-end runs a thread of creativity, possibility, and self-expression."

If you're interested in taking up some small projects, I once wrote a simple guide on how to replace lost or broken buttons. Edwin Zee and Reddit member AnalogDimitri have tutorials on how to darn a hole by hand. If you're really ambitious, here are some posts on how you can start making or altering clothes at home. Finally, for jobs that ought to be handled by a professional, I once wrote a directory for reliable service providers (and, relatedly, a basic guide to alterations).

In the meantime, I have a small hole in my sweatshirt that I need to fix.