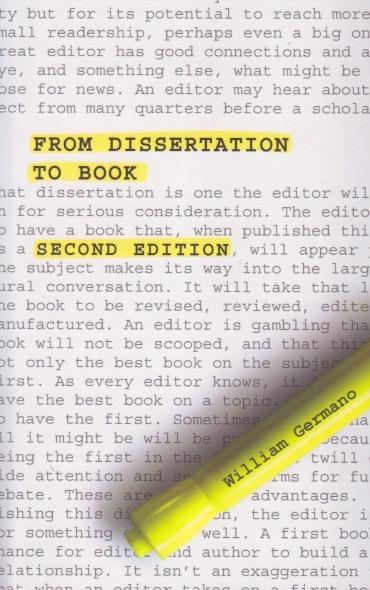

When I worked at Routledge I was told never to mention William Germano’s name. I’ve never been one to dabble in workplace politics, but I did wonder why. Over time, as I tried to commission the kinds of books I knew Routledge for, I was told that they didn’t do those kinds of books. Not since the Germano days. Years later I still don’t know what all of that was about, but I do know that Germano wrote a book that would make nearly every academic editor’s life easier if it were handed out at every doctoral graduation ceremony. From Dissertation to Book is a classic in the field. Now in its second edition, in it Germano explains, in non-technical language, why and how a dissertation is not a book. He also explains how to make it a book.

You see, academic editors, such as yours truly, see more dissertations than the most ambitious professor. The doctoral student, flush with the praise of his or her examination committee, sends off their thesis, largely unchanged, and wants it to be published. Hey, don’t be embarrassed—that’s what I did too. The truly amazing thing to me, as someone who’s been both professor and editor, is how little publishing and academia know about each other. If I had to guess who knows whom better, I’d have to say publishers take an edge over academics. Their knowledge is far from perfect, however. Academics have to publish for promotion and tenure, but they don’t bother to learn about how publishing works. Germano’s book would help them too.

For many years well-known academics have been stating in highly visible places that academic writing is poor writing. It is. Germano explains why in this little book. Better than that, he gives solid advice on how to improve your chances of getting published. I’ve been working in academic publishing for a decade and a half and I learned quite a lot from this little book. Dissertations are written to prove yourself to a committee. Books are written for a wider readership that wants to be able to understand what you’re talking about. Day in and day out, people like myself read dissertations. Generally there’s a kernel of something good there. (Sometimes, honestly, there’s not. Not all theses are created equal, although that’s not one of the ninety-five.) Germano’s book offers a way to find and plant that kernel so that it grows into something any editor would be pleased to receive—the proposal for an actual book. It should be read widely—much more widely than it is.