One of the hardest aspects of my job is getting students to feel as enthusiastic as I do about the texts I’m teaching. With my university degree and several more years’ of life experience, I can usually analyze texts at a far greater depth than they can, and can relate to the emotions being expressed more directly. Passages that have reduced me to tears often leave my students cold, and poignant explorations of the dilemmas we face as we progress into adulthood are lost on the naivety of youth. Beautiful linguistic expression is dismissed, with a roll of the eyes, as ‘boring’ and the sight of any word that is polysyllabic results in the whining of that most annoying of phrases – ‘Miss, I don’t get it.’ Plots that seem slightly unfeasible (hello, Shakespeare’s entire canon) are simply ‘stupid’ and ‘pointless’ and anything that takes place more than ten years ago is clearly impossible to relate to in any way as ‘the people are like, from the olden days, Miss.’ I have lost count of the times I have looked up from the pages of a book, mid flow, to see several children staring out of the window, lying down on the desks, or up to some sort of mischief, while I have been transported to another world. As someone who has always been entranced by the worlds opened up to me through literature, I struggle to understand why some children can’t allow themselves to be swept away by words on a page.

However. Amidst the sea of rolling eyes, sighs, and doodles, I have managed to captivate a few minds. Teaching a novel is about more than sharing a story; it’s about inviting people to step into an alternate reality, and experience life from a different perspective for a while. It’s about showing them how to look beyond the surface, and find deeper meaning beneath what is literally printed on the page. It’s about getting them to decipher the clues left in the narrative that point to the author’s intentions. It’s about encouraging them to develop a critical voice; to question, to probe, to analyse, to evaluate. Studying novels makes us more enquiring and empathetic people; it makes us more aware of the way in which we construct the narratives our lives, of how we can manipulate language to suit a particular end, of how other people live and love and engage with one another. It allows us to consider how we would cope in situations we are yet to experience. It allows us to fall in love, to become irate, to make friends, to be inspired, to develop courage, to bring about change; all without leaving the comfort of our own homes.

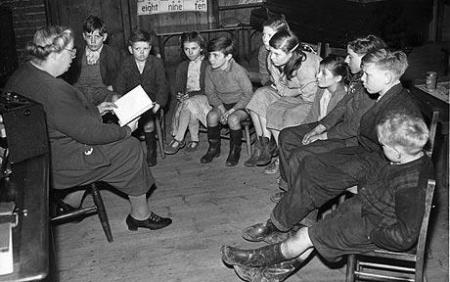

So how do I manage to communicate all of these things? Well, the answer is as varied as the classes I teach. Sometimes we act out the events of the novel; through dramatising what is happening, we can engage more fully with the emotions being expressed. Sometimes we have debates, and trawl through the novel to find evidence that supports our varied perspectives of events. Sometimes we analyze a particular passage in detail, and are amazed at what alternative meanings we find behind a line of seemingly innocuous text. Sometimes we recreate the setting of a novel as a wall display, bringing the world of the novel to life through sugar paper and paint. Sometimes we make masks of the characters’ faces and walk around the room pretending to be them, channeling their emotions and emulating their voice and gestures to truly feel what it is to walk in their shoes. Sometimes we draw pictures, or make posters, exploring our impressions of the novel in a more creative way. Sometimes we rewrite a scene to explore an alternative outcome, or add a scene that didn’t actually happen. Sometimes we update the events of a novel to the present day, helping us to appreciate how people and their everyday concerns don’t really change over time. Sometimes we rewrite the events of the novel as a rap and perform it. Sometimes we model our favorite scenes in play-doh. Sometimes we just talk about how the story makes us feel, and we share our own experiences of the situations the characters are living through.

Whatever we do, I try and get the students to connect with the story on a personal level. Transcending the barrier between fiction and reality is vital if a student is going to come to care about a text and the message it is attempting to relay. My proudest teaching moment so far has been reducing my entire class of too-cool-for-school 15 year olds to tears as we finished reading Romeo and Juliet. As I read the lines ‘for never was a story of more woe than this of Juliet and her Romeo,’ a wave of sniffles went around the room, and, glassy eyed, they started complaining about how unfair it all was. ‘It’s all their parents’ fault!’ one shouted, irate. ‘They should have listened to what they wanted!’ ‘No!’ shouted another. ‘It’s Friar Lawrence – he was the one who came up with the whole stupid plan in the first place!’ Before I knew it, everyone was busy debating their perspective, eager to find some resolution, someone to blame, for the perceived travesty of two teenagers needlessly dying in front of them. I couldn’t believe this was the same class who had groaned their way through the first few scenes of the play, moaning about the language being too hard and the characters having stupid names. Somewhere along the way, I’d managed to convince them that this story mattered. And that, far more than any exam grades they achieve, is what I call a success.