By Alan Bean

By Alan Bean

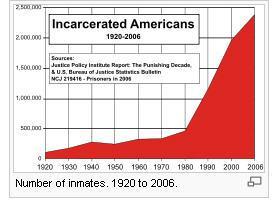

The graft to the left shows how the prison population exploded after 1980. Part of the blame for this nightmarish experiment with big government must be laid at the feet of Wayne LaPierre and the NRA.

The goal was to raise money for the cash-strapped anti-gun regulation organization. Accusing the Clintons (both of them) of being soft-on-crime was a great way to catch the attention of conservative Americans shocked by the apparent demise of the Reagan revolution. Banging the drum for more prisons, mandatory minimum sentences, and the defunding of rehabilitation, re-entry and alternatives-to-prison programs fit the tenor of the times.

In 1992, when the NRA’s “lets-build-more-prisons” campaign got underway, Bill Clinton, like every other American politician, was doing his best to talk tough on crime. The NRA’s goal was to talk tougher, even if that meant spewing utter nonsense and supporting ruinous policies. You rarely see mass incarceration identified as a massive tax grab, but that’s exactly what it is.

The success of the Reagan-Bush experiment required talking small government while pouring untold billions into the military and the prison system while no one was looking. Hundreds of thousands of American investors got rich in the process. But the result, as any true conservative realizes, was exploding government debt and a host of expensive jobs programs that, once in place, proved impossible to eliminate. This wasn’t government waste; it was about patriotism and public safety. This combination of patriotism, fear-mongering and crony capitalism made it virtually impossible to scale back the American military and explains why the prison rate holds steady in the face of dramatic, across-the-board declines in crime.

The NRA didn’t really care about public safety, people like the odious LaPierre were just looking for a way to pay the bills. Fueling American paranoia has always been a can’t-miss proposition for fund raisers and charlatans of every stripe.

Please read this article from Mother Jones.

The Big House That Wayne LaPierre Built

The NRA spent millions in the 1990s pushing the largest prison construction boom ever—and harsh sentencing to keep them full.

Tim Murphy

February 8, 2013

It sounded like a throwaway line. Toward the end of a four-hour Senate hearing on gun violence last week, Wayne LaPierre, the National Rifle Association’s executive vice president of over two decades, took a break from extolling the virtues of assault rifles and waded briefly into new territory: criminal justice reform. “We’ve supported prison building,” LaPierre said. Then he hammered California for releasing tens of thousands of nonviolent offenders per a Supreme Court order—what he’d previously termed ”the largest prison break in American history.”

But California’s overflowing prisons, which the Supreme Court had deemed “cruel and unusual punishment” in 2011 because of squalid conditions, were partly a product of the NRA’s creation. Starting in 1992, as part of a now-defunct program called CrimeStrike, the NRA spent millions of dollars pushing a slate of supposedly anti-crime measures across the country that kept America’s prisons full—and built new ones to meet the demand. CrimeStrike’s legacy is everywhere these days.

CrimeStrike arose out of necessity. The NRA had come into its own as a political power during the Reagan era, but by the early 1990s, it was strapped for cash. The organization ran up a $9 million deficit in 1991 and was on pace for a $30 million shortfall in 1992, even as it was preparing to go to the mattresses over assault weapons and background checks. The NRA needed a shot in the arm.

LaPierre launched CrimeStrike that spring with $2 million in seed money from the parent organization and a simple platform: mandatory minimums, harsher parole standards, adult sentences for juveniles, and, critically, more prisons. “Our prisons are overcrowded. Our bail laws are atrocious. We’ll be the bad guy,” he announced.

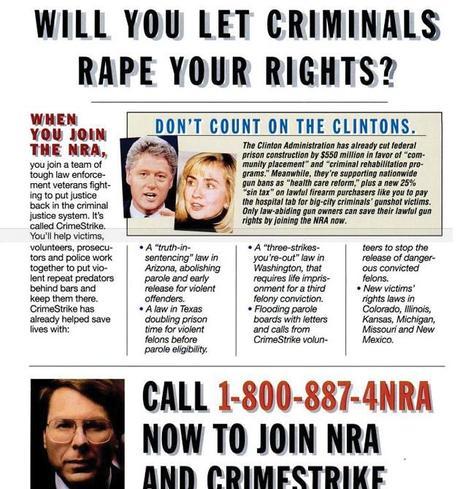

The NRA took its case to the public. “Will you let criminals rape your rights?” asked a four-page ad in a 1994 issue of Field & Streammagazine. And the real culprit was in the White House: “The Clinton administration has already cut federal prison construction by $550 million in favor of ‘community placement’ and ‘criminal rehabilitation programs.’” This was reviving an old conservative talking point: Democrats were soft on crime. The ads featured LaPierre’s signature and bespectacled, stoic face at the bottom, alongside a 1-800 number interested volunteers could call. It was a membership hotline.

A month later, CrimeStrike took out a full-page ad in USA Today asserting that then-Rep. Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) “wants to rob the crime bill of $8 billion that could be spent building the prisons that put bars between criminals and your family.” The NRA fix: “Tell them you want a crime bill with $8 billion more to build prisons, or you don’t want their crime bill at all!”

Although the NRA lost on the assault weapons front, it got what it wanted in one respect: funding for prison construction increased threefold. That was on top of its own concurrent successes at the state level. In 1993, in the midst of what advocates on all sides agreed was a serious crisis, Texas held a referendum on a $1 billion bond for prison construction. The NRA spent big on advertisements in support of the initiative, which would expand the state’s capacity by 37,000 beds. It passed, along with a package of reforms designed to make it much harder for convicted felons to go home early. (A $750 million bond for school construction failed, however.) That was a driving force in what the Houston Chronicle described as “the biggest prison construction boom in U.S. history”—18 new state jails at a cost of $3 billion, in just five years. CrimeStrike lobbied successfully for similar construction projects in Mississippi and Virginia.

States needed prisons in part because the NRA was pushing a legislative agenda designed to keep them full. In 1993, CrimeStrike spent $90,000 to put on the ballot in Washington state a new kind of sentencing law called “Three strikes and you’re out,” in which third-term offenders would be given a mandatory life sentences, on the ballot. Voters in the state passed the measure. The next year, CrimeStrike set its eyes on a bigger prize: California.

Mike Reynolds, a wedding photographer from Fresno, had been pushing for a three-strikes law in the Golden State ever since his daughter was murdered by a repeat offender in 1992. But his previous attempts at getting it on the ballot fell well short. Enter CrimeStrike. The NRA dropped $130,000 in support of the initiative (much of it early) and worked with the state’s biggest prison guard lobby to collect signatures. “That was very instrumental at getting us up and going,” Reynolds says. The measure set off an avalanche. Within just a few years, 23 states had enacted variations of the three-strikes statutes.

By the late 1990s, after attempting to block the Violence Against Women Act (over a provision that would have disarmed abusive spouses) and fighting to curtail prison weightlifting programs, CrimeStrike had outlived its usefulness and was quietly phased out. But its accomplishments had been literally set in stone. Thanks to stricter sentencing guidelines and increased capacity, the United States was locking up more people than at any point in its history, and for longer. Even as violent crime dropped across the country, incarceration rates continued to increase.

The number of people serving time in state or federal prisons increased 100 percent between 1990 and 2005. But California and Texas, the two states where the NRA had expended the most capital, were the most striking examples. The Golden State’s three-strikes law differed from most of the other 29 in that it applied to an exceedingly broad definition of what amounted to a “strike.” Under its guidelines, nonviolent crimes—including, in one famous case,the filching of a slice of pizza—were enough to put someone behind bars for life.

“There’s actual real-life academics who have studied this stuff, and there’s actually no evidence whatsoever it’s had an impact,” says Marc Mauer, executive director of the Sentencing Project, a criminal justice nonprofit.

But mandatory life sentences ensure that thousands of inmates will grow old behind bars, which is rather expensive. Senior-citizen inmates cost the state about twice as much per year (approximately $68,000) than their younger counterparts, due to health care expenses—even as those inmates become increasingly less likely to commit crimes should they be released.

The prisons became simultaneously more crowded and more expensive to maintain. Writing for the majority in 2011, Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy noted that inmates in California were forced to live in “telephone-booth-sized cages without toilets,” and often went more than a year without receiving medical attention. The state’s corrections system, Kennedy argued, was “incompatible with the concept of human dignity and has no place in civilized society.”

The consequence of California’s reforms is that Texas now leads the nation in incarceration, with 154,000 people behind bars—more prisoners per capita than all but three countries. The construction boom addressed what criminal-justice watchdogs considered to be a serious problem: Violent felons were being released before they were even eligible for parole because there simply wasn’t any room. But CrimeStrike and its allies did nothing to curb the underlying problem—a sentencing system that locked people up for the smallest of crimes, kept them there for a while, and openly mocked efforts to keep them from coming back.

All that’s left of the NRA’s prison-building arm 20 years later is a television show by the same name. Hosted by LaPierre, Crime Strike features weekly reenactments of gun owners defending their turf, with the mantra: “Take aim and fight back.” But the program’s legacy lives on in concrete ways.

Prisons “cost $3.3 billion a year in Texas alone,” says Michele Deitch, a lecturer at the University of Texas. “Around the country it adds up to about $52 billion a year. It’s just a phenomenal cost, and what social cost is this causing?”