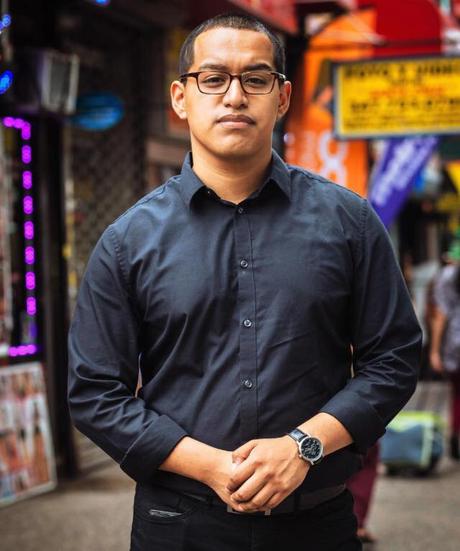

Hernan Carvente

Hernan Carvente was born into an unstable home environment, rife with alcohol and domestic abuse and devoid of any resources that could help him and his family escape these cycles of violence. Carvente was drinking by the age of eight, gang affiliated by 13, and just 16 years old when he was convicted of a violent crime that resulted in four years of incarceration in a maximum-security juvenile facility.

Hernan, like most youths in juvenile detention, had to rely on the facility itself for rehabilitation—a service that would supposedly present the opportunity for incarcerated teens to find the tools and take the measures necessary to remedy the trajectory of their lives. But Brookwood Detention Center, two hours north of New York City, didn’t facilitate an environment for development.

In the facility, Carvente and his incarcerated peers were deprived of “adequate mental health services, a quality secondary education program, and pro-social opportunities,” he told MTV News’s Julie Zeilinger in an interview. Chief among the facility’s deficiencies was the fact that it was over two hours away from Carvente’s family and community, which isolated him from his loved ones, as well as the prospective education and work opportunities that would be available to him upon release. The program mostly reiterated the patterns that led youth to get locked up in the first place, in perpetuity. Essentially, Carvente’s stint in juvenile detention was an exercise in trying to dry mud with water: You can’t remedy an issue by applying the same issues that created it.

When Carvente was released in June 2012 at age 20, he went on to become an advocate for youth all around the country. Currently, he serves as an advisor to the Youth First Initiative, a national advocacy campaign that is looking to end youth incarceration by closing youth prisons and investing in community-based alternatives. Carvente’s personal experience with youth incarceration not only offers the organization a crucial yet often overlooked perspective on youth justice reform, but also dictates their campaigns and larger approach to addressing inconsistencies in policy. For example, Carvente, who identifies as Latinx, says that “we can no longer escape the blatant racial inequalities in our system.” Sustainable reform has to reflect the experiences and voices of the youth and families who have lived it firsthand, according to Carvente. Who better to point out the system’s flaws than those who spent months or sometimes years surrounded by its every inescapable deficiency?

Youth justice reform efforts offer alternatives to the punitive treatment models currently employed by the system, during which trained officials try to help rectify the problems these youth face post-incarceration as best they can. They listen to and champion the voices of those who have been in juvenile detention as well as those who have since been released from it, and pair them with enthusiastic and dedicated mentors and educators. They believe that their voices should be heard when panels or talks are given on the youth incarceration system, not only because they’ve been in the same detention centers as those being discussed, but also because they often come from the same communities. This gives credence to those who have spent time incarcerated and acts as proof for those currently detained that there are opportunities for success upon release.

But these programs often fail, not as much because of their work as because of the stigma surrounding incarceration that still exists among the general public: Countless individuals are “marked” by their incarceration. How can a program rehabilitate someone if the public i they’re supposedly being prepared for is not willing or able to ever see them as changed?

“It wasn’t that long ago that upon being invited to tell my story, I felt like I shouldn’t say I was convicted of a violent crime, because of the perception,” says Carvente. Few people are able to see beyond the charges and sentence of someone who was formerly incarcerated, which often eliminates their schooling and employment opportunities, and, even broadly, being accepted back into society post-incarceration. As Carvente put it, “It’s like you never truly finish serving your sentence; even after you have fully turned your life around, society forces you to carry that burden for the rest of your life.”

We have to release the stigma that surrounds someone with a criminal past—especially if that past is informed by drug-related or other forms of physical or emotional abuse. We can no longer allow entire swaths of citizens to be barred from receiving help because the facilities intended to do just that are inadequate. As Carvente put it: “It is not just about changing how our current system works,” but also about ensuring future youth have at least an opportunity to succeed, regardless of the environment and circumstances in which they were raised.