E. Glenn Hinson and Alan Bean, June 2019

E. Glenn Hinson and Alan Bean, June 2019E. Glenn Hinson is a professor of church history who specializes in spiritual formation, Christian contemplation, inter-faith dialog and peace making. For thousands of American Christians, Baptist and otherwise, Hinson symbolizes hope, vision and rectitude. Bailey Smith was, until his death in January, 2019, an icon of the “conservative resurgence” within the Southern Baptist Convention.

Hinson, like scores of his spiritual kinfolk, was scapegoated, harassed and finally driven out of a denomination he had faithfully served for over half a century. Smith became SBC president and assumed iconic status within the denomination.

Both men were dedicated to serving God, but the events described below clearly demonstrate that Hinson’s God was an abomination to Smith and vice versa. And yet many American Christians, perhaps most, are still trying to make room for both deities. We worship a schizophrenic God who combines irreconcilable traits. The story you are about to hear demonstrates why that is a very bad idea.

The marriage between the religious right and the Republican Party was consummated in Dallas, Texas on the twenty-first of August, 1980 at the Public Affairs Briefing organized by Ed McAteer of the Religious Roundtable organized and a holy host of evangelical luminaries. It was billed as a bipartisan affair but from the moment James Robison warmed up the crowd for Ronald Reagan the true intention of the gathering was obvious. “God’s angry young man” waved his Bible over his head as he demanded that “both parties and politicians align themselves with the eternal values of this book.” If that happened, Robison promised “America will be forever the greatest nation on this earth.”

That line brought the crowd of evangelical leaders to its feet. Reagan’s handlers tried to get him to wait in the wings while Robison warmed up the crowd and W.A. Criswell delivered a formal introduction. They didn’t want their man associated too closely with Jerry Falwell and his crew. Reagan had other ideas. Ignoring the protestations of his advisers, the Great Communicator strode to the center of the stage and plopped down right beside James Kennedy.

When Robison insisted that the Bible, and the Bible alone, should be the guiding light for American public policy, Reagan leaped to his feet with everyone else.

Reagan also applauded enthusiastically, moments later, when Robison suggested that members of the Carter administration should be “locked up” for printing money “as worthless as toilet tissue” to pay for wasteful social programs.

Ronald Reagan and James Robison

Ronald Reagan and James RobisonThe most often-quoted comment of the evening was Reagan’s opening line: “I know you can’t endorse me, but I endorse you, and what you are doing.” The wording had been suggested by Robison as he and Falwell rode in Reagan’s limousine from the airport. “That’s perfect,” Reagan said, “let me write that down.”

Reagan and his entourage were flying to their next engagement by the time Bailey Smith, the president of the Southern Baptist Convention took the podium. The pastor of First Baptist Church of Del City, Oklahoma was impressed by the relative homogeneity of the faces behind him as well as those in the audience. “It is interesting,” he remarked casually, “at great political rallies, how you have a Protestant to pray, a Catholic to pray, and then you have a low to pray. With all due respects to those dear people, my friends, God Almighty does not hear the prayer of a Jew.”

Jerry Falwell applauded politely along with everyone else, but he was appalled. He had spent the better part of 1979 courting not only Ronald Reagan but also members of the conservative Likud party in Israel. His friends in Likud knew that Falwell believed they were eternally lost, but so long as he kept his weird theology to himself they were willing to play along.

Falwell was such a valuable ally, in fact, that Likud presented him with his own private jet.

The creator of the Moral Majority was championing an ecumenism of the right, an amalgam of conservative evangelicals, Catholics and Jews that would preserve the religious character of America by linking arms with conservative politicians, economists and the business community. Falwell maintained a laser focus on the place where the interests of this diverse assemblage overlapped.

And now Bailey Smith had to shoot off his mouth. What a blessing that the media scrum had vacated the building the moment Regan concluded his remarks.

But Milton Tobian, executive director of the American Jewish Committee’s North Texas region, had been in the audience that night and had Bailey Smith’s words on tape. Tobian made a transcript of Smith’s remarks and sent them to every major Jewish leader in his rolodex.

So it was that E. Glenn Hinson, a church history professor at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky, received an unexpected phone call. Sol Bernards, Director of the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith was calling from New York. “I’ve called every Southern Baptist leader I can think of,” Bernards said, “and cannot get a single one to respond to this statement.”

Hinson had been deeply offended by Bailey Smith’s remarks, but the thought of publishing a response had never occurred to him. Since Hinson couldn’t speak for the seminary or the Southern Baptist Convention, he suggested that Bernards look elsewhere. He suggested that Duke McCall, the president of Southern Seminary would be happy to make a statement.

Two days later, Bernard was back on the phone, “Glenn, I’ve called McCall’s office repeatedly,” he said, “His secretary always cuts me off.”

“Okay, Sol,” Hinson replied, “I’ll make a statement.”

Duke McCall was deeply offended by Smith’s scurrilous comment, but he had bigger fish to fry. Three weeks after the Public Affairs Briefing in Dallas, Houston Judge Paul Pressler told a group of fundamentalist pastors in Lynchburg, Virginia that “we are going for the jugular.” If the conservative faction could elect a series of fundamentalist presidents, Pressler argued, they could eventually remake the Southern Baptist Convention by stocking the boards of every denominational entity with fundamentalists.

Bailey Smith’s willingness to play his part in Pressler’s scheme worried president McCall much more than the Oklahoma preacher’s comments about Jews.

Glenn Hinson sat down at his 1923 Underwood and tapped off a response to Bailey Smith. Hinson’s voluminous writing was always produced under onerous time constraints and he had mastered the art of churning out succinct, error-free prose. He had five big beefs with Smith’s comments.

- If God does not hear the prayer of a Jew, he couldn’t hear the prayers of Jesus.

- If God does not hear the prayer of a Jew, the prayers of Abraham, Moses and the prophets went unheard.

- Smith’s remark violated the traditional Baptist concern for religious liberty and the principle of Church-State separation going back to Roger Williams.

- Throughout the New Testament God hears the prayers of non-Christians like the Roman centurion in Acts 10.

But it was the fifth objection that made Hinson a marked man:

- “Statements such as this one are the stuff from which holocausts come.”

That night, at 2:00 in the morning, the professor was in his rocking chair pondering the wisdom of publishing his letter. (His conversation with the Creator is recorded in his autobiography.) “God, you can’t expect me to do this,” Hinson lamented. “I’m an irenic person. I got sick of fighting when I was in knickers. You surely don’t mean for me to send out a letter that may cause all hell to break loose.”

Finally, the answer came, “Yes, dammit, Glenn, hang in there!” Marching orders in hand, Hinson returned to bed, slept like a child, and mailed his letter to the Western Recorder, the Kentucky Baptist state paper.

The first indication of trouble was a Friday-morning summons to Duke McCall’s office. “Glenn,” McCall hollered, “you’ve got to do something about this. It’s explosive!”

Hinson wasn’t in the mood for a fight. As with most weekends, he had a speaking engagement, this time with a Methodist Church in Erie, Illinois. “I’ll have to attend to this on Monday,” Hinson said, then turned on his heel and marched to the taxi waiting for him in the circular driveway in front of Norton Hall.

Duke McCall

Duke McCallBut the issue wouldn’t wait. His good friend Frank Stagg called him in Erie late that afternoon. Duke McCall had told a faculty meeting that he had no choice but to make a statement, “but I don’t want to, for it will kick Glenn in the face.” After passing through the grapevine, this remark got back to Hinson’s wife, Martha as “If I had Glenn Hinson here, I would kick him in the face.”

The next day, in between presentations to his Methodist audience, Hinson fielded a series of phone calls from alarmed colleagues. Most were supportive, but Hinson’s letter to Smith was spreading like wildfire and some feared it would do irreparable damage to the seminary. Hinson was feeling lightheaded. He was almost never sick to his stomach, but between presentations to the Methodists, he was in the restroom throwing up violently.

Shortly after threatening to throw Hinson under the bus, McCall headed to Gatlinburg, Tennessee for a meeting arranged by his good friend Cecil Sherman. Twenty-five seminary presidents, prominent pastors and denominational leaders had been invited to a conference room in a Holiday Inn for an emergency confab. A cabal of fundamentalist preachers were determined to remake the Southern Baptist Convention in their own image and the old guard needed a strategic response.

No one was in favor of the kind of direct engagement Hinson represented. Bailey Smith’s remark in Dallas might have been hateful, but it followed the logic of Southern evangelicalism. Jesus said, “I am the way, the truth and the life, no man cometh to the Father but by me.” Ergo, only those who accepted Jesus as Savior had access to the throne of mercy.

The “Gatlinburg gang” (as they came to be known in conservative circles) knew they couldn’t tangle with Bailey Smith without sounding like Unitarians. If Jews could be saved without Jesus, what about the Muslims and the Hindus and the Buddhists? What’s the point of sending missionaries?

Since the end of World War II the Southern Baptist Convention had been growing at an almost cancerous rate. By the 1960s, the SBC was the largest protestant denomination in America and the great need of the hour was finding pastors for all the new churches springing up across the Southland. Men with organizational and administrative skills assumed control of the denominational apparatus. The leaders gathered in Gatlinburg were used to calling the shots and handing out plum positions to successful pastors, most with earned doctorates from the denominational seminaries, who, through message-discipline and support for the denominations cooperative program, had earned that right.

The men gathered in Gatlinburg saw themselves as theological conservatives and, in comparison to their counterparts in the Protestant mainline, they were. Russell Dilday, president of Fort Worth’s Southwestern Theological Seminary reminded his colleagues in Gatlinburg, “Baptists, 99% of them, had this high view of total trustworthiness of Scripture and even if they didn’t use the word, the idea of inerrancy was the position that Baptists held without any question of confidence in the word of God.”

The only solution to the fundamentalist challenge was to ensure that a member of the good ole boy network challenged Smith for the presidency the following year. In the meantime, public controversy must be avoided at all costs. Which is why Duke McCall was wishing both the preacher from Oklahoma and the highly esteemed Dr. Hinson had kept their mouths shut.

When Smith’s incendiary remarks made national headlines, several Southern Baptists criticized the SBC president for being uncivil and intolerant. But Hinson had suggested, not so subtly, that the spirit of fundamentalism was not far removed from the zeitgeist in Nazi Germany. He was implying that there was something sinister afoot in the Southern Baptist Convention. Smith was suggesting that Jewish Americans should be expelled from the public life of the nation; a threat that, for those with ears to hear, sounded all too familiar.

Which explains the sudden shift in my story. On Sunday morning, Hinson’s colleague Wayne Ward called with unexpected news: “Glenn,” he said, “you’re a hero!”

The Jerusalem Post had printed Hinson’s letter just as the Israeli Knesset was on the verge of expelling every Southern Baptist missionary in the country. The fact that a leading Southern Baptist scholar had denounced Smith in precisely the right terms had changed their minds.

Bailey Smith and Glenn Hinson both grew up in the Southern Baptist Convention but they worshiped very different Gods. At no point during his years at Ouachita Baptist College in Arkadelphia, Arkansas and Southwestern Seminary in Fort Worth was Smith challenged to rethink the pop theology he had learned in Sunday school. His doctoral degree was honorary.

By contrast, Hinson did his undergraduate work at Washington University in Saint Louis where he studied comparative religion under Huston Smith. After reading the sacred literature of the world’s great religions, the young Southern Baptist experienced a crisis of faith. What made him so sure that Christians were right and everybody else was wrong?

And then one night he awoke with a jolt and sat upright in bed with the words of Jesus ringing in his head, “You shall know the truth, and the truth shall set you free!” Whatever is true, he suddenly realized, is of God, no matter where it is found. This encounter with the divine was so powerful that Hinson never again doubted that God was real, powerful and accessible.

Russell Dilday may have been right when he surmised that 99% of Southern Baptists believed the Bible was without error, but you would have had trouble finding a professor teaching at one of the denominational seminaries who shared this confidence. Hinson’s respect for all the great religious traditions of the world was not challenged by what he learned at Southern Seminary. A gifted linguist with a prodigious memory, Hinson entered Southern in 1954 already able to sight-read the Greek New Testament. Doctoral study at Southern and Oxford introduced him to new languages, ideas, and traditions. Trained as a New Testament scholar, Hinson shifted his attention to church history because that’s what the seminary needed.

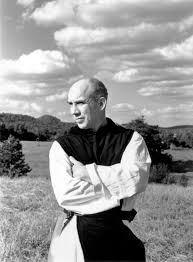

Thomas Merton

Thomas MertonBut it was Hinson’s encounter with a Thomas Merton, a Trappist monk in an abbey just down the road from Louisville that made him a true ecumenist. When I visited with my old professor in June he told me that Merton’s impact was gradual. In the early 1960s he arranged to take a church history class for a tour of the Abbey of Gethsemani so they could get a feel for medieval monasticism. After the tour, Merton gave a brief lecture to Hinson’s students and invited questions. One student, impressed by the monk’s simple eloquence, asked what such a smart guy was doing tucked away in the hills of Kentucky. Merton was greatly amused by the question and, once his laughter abated, he explained gently that his vocation was to pray for the world.

Merton’s sense of vocation sprang from a mystical experience on the streets of Louisville two years earlier. As the shoppers whizzed by, oblivious to one another, “I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realization that I loved all those people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers.”

Hinson started teaching courses in Christian Spirituality in the early 1960s, but it wasn’t until after Merton’s tragic death in 1968 that he began to understand what his monkish friend had been talking about. Leafing through a series of lectures that Merton had handed him years earlier, the Southern Baptist professor was reintroduced to his own religion. He immersed himself in the fathers and mothers of the Church, ancient and contemporary, and was amazed by what he discovered.

Hinson completed his formal education with a Doctor of Philosophy in patristics from Oxford University, sequestering himself in the Bodleian Library where he read virtually everything written by leading Christian thinkers before 400 CE. The Church of England, he learned, “ascribes to the Fathers [and Mothers] of the Church the kind of respect and authority for framing its doctrine most Protestants accord to the New Testament.”

In the course of his studies, Hinson also was introduced to Eastern Orthodoxy with its focus on the Logos Christology and “theosis” (the idea that God became human so humans could partake in the Divine). This prepared him for the thought of the paleontologist/theologian Pierre Teilhard de Chardin who spoke of Christ as the “Omega Man,” the culmination of eons of biological and spiritual evolution.

In the same gospel where we find Jesus saying that no one comes to God except through him, we are told that the Christ “was in the beginning with God; all things were made through him, and without him was not anything made that was made.” And that “In him was life, and the life was the light of men.”

That same gospel tells us that John the Baptist was sent “to bear witness to the light, that all might believe.” When the Baptist sets eyes on Jesus he cries, “Behold the Lamb of God who taketh away the sins of the world.” The divine Word became flesh “that the world, through him, might be saved.”

Later in John’s Gospel, Jesus tells his disciples that when he is lifted up he will draw (literally ‘drag’) all humanity to himself.

Thus, the One who identifies as “the way, the truth and the life” is the universal Christ who comes into the world on a mission of universal salvation.

This theological perspective transformed Hinson into the ultimate ecumenist. Christianity was a distinct religion with a unique message, he insisted, but the truth of Christ is not limited to Baptists or even to Christians. This is why Christians can find a deeper appreciation of their own faith tradition through respectful dialog with non-Christian persons of faith.

But Hinson’s radical ecumenism wasn’t just focused on learning from other religions; he also wanted to heal the wounds created by bigotry, ignorance and misunderstanding. His involvement in the peace movement was just another form of Christian discipleship.

If healing was at the heart of Glenn Hinson’s spirituality, hell was central to Bailey Smith’s religion. If what Jesus said was central to his significance, Smith believed, God would have let him life to a ripe old age, but Jesus came to die and “there is only one reason Jesus died, and that’s because there is a literal hell.”

Bailey Smith in 1981

Bailey Smith in 1981Smith was elevated to the presidency of the Southern Baptist Convention on the strength of a single statistic: he had single-handedly baptized 2,000 people in a single year. Smith accomplished this feat by asking his audience to think back to the moment they first gave their heart to Jesus. Southern Baptists believed in the importance of pinpointing, down to the minute, when they were saved. Smith’s genius was to make his listeners question whether they had been really and truly saved. Because, if they didn’t get their religion right way back then, they were headed straight for the pit.

Smith was influenced by a uniquely Southern Baptist heresy known as “Martinism” after the turn-of-the-twentieth-century Mississippi preacher,Matthew Thomas Martin. If you weren’t 100% sure of your salvation, Martin taught, you clearly weren’t saved. It followed, therefore, that if you gained the confidence of the true convert you should be re-baptized. Long after Rev. Martin was long forgotten, his theological influence remained in the rural South.

Smith knew that, especially in the American South, Christianity was closely associated with respectability. During the 1950s and 60s, millions of people joined Southern Baptist churches because it was the “done thing”. But being a good person and going through the religious motions wouldn’t save you, Smith told his people.

In his sermon “Seven kinds of people God will not save” Smith placed Pharisaical religion in his homiletic cross-hairs. “What would you have if you had a church full of Pharisees?” he asked rhetorically. “They’d be there Sunday morning, Sunday night, church training, Sunday school, they’d give 20% of their income, they’d pray three times a day, they’d memorize scripture and they’d all die and go to hell.”

Or maybe you “went forward” at an evangelistic meeting when you were nine or ten because your best friend wanted to and you thought you should. If so, Smith informed his listeners, both you and your friend are very likely “a heartbeat from hell”.

In God’s Last and Only Hope: The Fragmentation of the Southern Baptist Convention, Bill Leonard diagnosed Bailey Smith’s revivalistic bread and butter.

Today, many Southern Baptists live on the edge of doubt about their conversion experience. At every life crisis many return to repeat the transaction and reclaim salvation, hoping against hope that they will finally get it right. Christianity is less a life of spiritual growth and struggle than a perpetual return to the beginning. The increase in the number or rebaptisms among Southern Baptist members is a dramatic phenomenon in SBC life. Some attribute it to the failure of revivalistic methods. Others suggest that, as the appeal of mass revivalism wanes, many Southern Baptists evangelists have concentrated on converting church members as a means to avoid changing their methods—or reducing their statistics.

When Smith became a full-time evangelist in 1985, his brother-in-law Tom Elliff succeeded him as pastor. One of his first moves was to purge the membership roll of thousands of non-resident and inactive members. When this process was complete it became evident that Bailey Smith had increased the membership of his church by only 470 during the five years he baptized 7297 people.

Although Smith never apologized for the anti-Semitic remark that gave him his fifteen minutes of fame in 1980, he eventually got with Falwell’s program. He made several trips to Israel and said all manner of nice things about the Jewish people. If you asked him, he would still say unconverted Jews were headed for the pit, but the conservative religious media that covered the kiss-and-make-up sessions between Smith and Israel were too polite to ask.

Still, by the end of his career, it was the Muslim world had become the target of Smith’s venom. No one criticized his remarks because, within the SBC, they had become standard issue.

In 2002, shortly after the 9-11 attack, Southern Baptist President Jerry Vines reprised Smith’s notoriety by launching into an anti-Muslim rant during a sermon at a pastor’s conference. “They would have us believe that Islam is just as good as Christianity,” Vines said. “Christianity was founded by the virgin-born son of God, Jesus Christ. Islam was founded by Muhammad, a demon-possessed pedophile who had 12 wives — and his last one was a 9-year-old girl . . . Allah is not Jehovah. Jehovah’s not going to turn you into a terrorist that will try to bomb people and take the lives of thousands and thousands of people.”

While George W. Bush scrambled to distance himself from Vines’ comment (just as Ronald Reagan had been forced to disagree with Smith in 1980), Southern Baptist preachers insisted that Vines’ comments were grounded in genuine scholarship.

Ergun Caner

Ergun Caner They weren’t. Vines had been reading the newly published Unveiling Islam: An Insider’s Look at Muslim Life and Beliefs, by Ergun and Emir Caner (pronounced “Kanner”). Ergun Caner had been on the evangelical speaking circuit for years claiming to be an aspiring Islamic terrorist won to Christ by the amazing grace of God. He attended Bailey Smith’s Real Evangelism conference for the first time in 1983 and was soon a featured speaker at that event and throughout the evangelical world. Barnstorming across the nation, Caner claimed to have been radicalized in Cairo in Beirut and suggested that, upon arrival in the United States, he was just like the folks who flew the airplanes into the Twin Towers.

Ergun Caner got most of their theology from Paige Patterson, then president of Criswell College in Dallas and, shortly after 9-11, his mentor suggested that Ergun co-author a book with his brother Emir.

Unveiling Islam was a big hit among Southern Baptists and Ergun was asked to become the first Muslim dean of Liberty College’s seminary. But critics (some Muslim, others Baptists of the Calvinist persuasion) hammered away at the Caner brother’s credibility until Liberty University refused to renew Ergun’s contract as dean. The evidence suggested that Caner had never been a practicing Muslim and, at best, had a superficial grasp of the religion.

Two years after being cut loose by Liberty, Ergun Caner was hired by Brewton Parker College, a Southern Baptist school in Georgia in 2013. Brewton Parker trustees had been fully briefed on Caner’s problems at Liberty University—that’s why they wanted him. “We didn’t consider Dr. Caner in spite of the attacks; we elected him because of them,” one trustee told the press. “He has endured relentless and pagan attacks like a warrior. We need a warrior as our next president.” Sound familiar?

Two years later, Brewton Parker’s warrior president had resigned after allegations surfaced of sexual impropriety and “racially disparaging” remarks.

None of these scandalous developments slowed the rise of Islamophobia within Southern evangelicalism.

The real burden of Bailey Smith’s theology was laid bare in a sermon titled “The Sin that Sounds So Nice” preached at Fairview Baptist Church in Edmond, Oklahoma, a few months before Donald Trump was elected president. Tolerance is “such an evil sin,” Smith declared, “because it contradicts the personality of God.” He then moved through his King James Bible listing all the times God had commanded his people to commit genocide.

God has never been known to be tolerant. ‘Those not found written in the Lamb’s book of life were cast into the lake of fire.’ Yeah. Where’s your sensitivity training God? You ought to be more tolerant . . . When God told Saul to go to the Amalekites and kill them all . . . When they marched around Jericho God said ‘kill them all.’ Had God been listened to back in that day we would not have an Arab issue today.

The genocidal seed Smith planted at the event in Dallas four decades earlier had come to full flower. But this xenophobic rejection of the “other” was just the flip-side of nostalgic white nationalism.

“Why are we not allowed to have America anymore?” Smith asked, his trembling voice suggesting that he had wandered off script. “Now, I know we can’t have the Walton America or the Andy Griffith America. That day will never exist anymore. And I’m sad about that. Because we had a right to have that kind of America, and it’s amazing how many of the Muslims and the other countries love to come here and enjoy the country children of God built.”

Is God a genocidal sadist arbitrarily picking favorites, or is God perfectly revealed in the enemy-loving Jesus?

Back in 1980, Jerry Falwell was praying that Bailey Smith would shut up about the Jews and Duke McCall was praying that Glenn Hinson would shut up about Bailey Smith. But we should be glad that both men spoke the unadorned truth as they understood it. The Smith-Hinson dust-up didn’t just foreshadow the coming storm in the Southern Baptist Convention, it revealed with stark clarity that the struggle wasn’t between conservatives and ultraconservatives, nor was it ultimately a fight between patricians and country preachers. The Baptist battles of the 1980s were about the character of God.

Glenn Hinson’s God was all about healing; Bailey smith’s God was all about hell. It was always radical ecumenism versus white Christian nationalism and, although few sided publicly with either Smith or Hinson, the two men staked out the only positions that can be logically and theologically consistent.

Smith and Hinson both have their disciples, but who can argue that Smith’s God has proven the most popular. Wide is the gate, and broad is the way, that leadeth to white Christian nationalism, and many there be which have entered therein. Straight is the gate, and narrow the way, which leadeth unto life and healing, and few there be that find it.

But, as Glenn Hinson likes to say, “The Baptist tradition depends on a minority consciousness.” A God of all-conquering love may not be popular, particularly in Baptist circles; but there is only one viable alternative . . . and as Bailey Smith and his ilk demonstrate, it ain’t pretty.

Moderate Baptists know they don’t want to follow Bailey Smith and his tribe, but have we embraced a clear alternative? Knowing who we aren’t won’t cut it anymore. The days of moderation are over. If the trumpet gives an uncertain sound, many of our children and grandchildren will walk out the door and never come back.

We need to tell the world who we are. Are we serious about talking to believers who don’t believe the way we do? Are we serious about lifelong spiritual formation? Do we want to be peacemakers? Are we interested in the radical inclusion Jesus talked about?

If we are, Glenn Hinson, now 88 years of age, still points the way forward.