These reflections were shared as part of a service at Broadway Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas, commemorating the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in Memphis, Tenn.

Minutes after I settled into my dorm room in Louisville, Ky., a young man with a deep Southern drawl dropped by to introduce himself. “I can’t believe seminary classes start tomorrow,” he said. “This is like a dream come true. I want to preach so bad I can taste it. Who’s your favorite preacher?”

“Martin Luther King,” I blurted back. It was either him or Billy Graham because they were the only preachers I could think of.

“Martin Luther King?” the young man said. “Wasn’t he some kind of communist or something?”

He wasn’t joking.

But my seminary professors stood four-square for civil rights and they told us so. King had been murdered in Memphis just seven years earlier and his name was always spoken in reverential tones. Professors told us that, back in the 1940s, it had been illegal to teach African Americans in the classroom, so they set up classes in the hallway.

I also learned that when Dr. King was invited to speak at Southern Seminary in 1961 the school lost $100,000 in donations in a single day. King had spoken, without notes, in a quiet baritone.

And then there was Clarence Jordan, the hero of Koinonia Farms in Georgia. The author of the Cotton Patch Gospels held a Ph.D. in Greek New Testament from Southern Seminary and everyone had a favorite Clarence Jordan story. (Jordan did for black preachers like King what Elvis did for Little Richard and James Brown–he took their music to a white audience).

The general idea was that Southern Seminary was an island of enlightenment adrift on a sea of ignorance.

But enlightenment had its limits. When Henlee Barnett (Southern’s equivalent of Southwestern Seminary’s T.B. Maston) reached retirement age the seminary refused to give him professor emeritus status, so we lost him to the University of Louisville. And the same administrators repeatedly told my wife, Nancy, to drop out of the M.Div. program because “our churches won’t ordain women.” She ignored them, of course.

Nancy was a year behind me and while I waited for her to graduate, I took a job delivering coffins and caskets to funeral homes in rural Kentucky and Indiana. To break the boredom, and insure that my beautiful mind wasn’t going to waste, I used to rent cassette tapes from the seminary library.

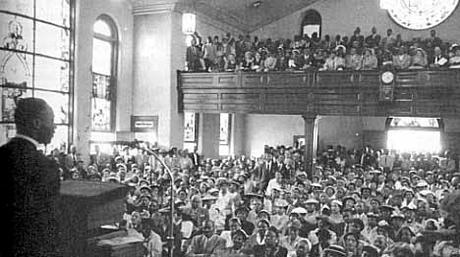

One day I checked out a tape labelled simply “Martin Luther King Jr.” The A side was Dr. King reading from his “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” When it was over, I flipped the cassette and found myself in the midst of a mass meeting. I now realize it was the inaugural address of the modern civil rights movement, delivered on Dec. 5, 1955, at the Holt Street Baptist Church in Montgomery, Ala. A few minutes after King was finished, the gathering voted overwhelmingly that no one would ride the city’s buses until they were integrated.

King spoke to 5,000 people that night. Two thousand were crammed into the sanctuary, hundreds more listened from the fellowship hall in the basement, and the church was encircled by a throng of people listening on loud speakers. King had agreed to serve as the mouthpiece for the Montgomery Improvement Association. He was just 25 years old and had been in Montgomery for only a year, but he had developed a reputation as a forceful speaker.

As I listened, my chest began to heave and, to my startled amazement, I was weeping uncontrollably. Blinded by the tears gushing from my eyes, I was forced to pull onto the shoulder. And there I sat in the cab of my three-ton delivery truck, sobbing like a little baby boy.

Over the years, I have struggled to understand my intense reaction to King’s address.

I realized that Martin Luther King could never preach like that without a crowd of fellow-sufferers urging him on. Preacher and congregation were singing in harmony. The words of even the most eloquent preacher will fall lifeless to the floor if nobody picks them up. But the words of Dr. King were scooped up and cradled lovingly by his listeners.

Now that I think of it, two sermons were in dialog with one another: one leaping from the lips of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.; the other preached by uncredentialed men and women who, to quote Fannie Lou Hamer, were “sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

Here are the words that grabbed me by the throat and wouldn’t let me go:

If we are wrong, the Supreme Court of this nation is wrong. If we are wrong, the Constitution of the United States is wrong. If we are wrong, God Almighty is wrong.

Was I part of the “we” in “if we are wrong”? Jesus came preaching to the poor, the oppressed and the outcast, the sojourner and the slave. If the gospel is for the poor, what are the privileged supposed to do with the gospel? Unless we become poor in spirit the gospel will be nonsense to us; an offense and a stumbling block. We become poor in spirit by identifying with the outcast, the oppressed and the persecuted. There is no other way.

I grew up in the most pious of Baptist families, but I put off baptism until I was 20 years of age because real Baptists were supposed to have a conversion experience and I hadn’t had one. Finally, I just went ahead and got ‘er done. But this experience, on the shoulder of I-64 west of Louisville, Ky., was my conversion experience. This was my Holy Ghost baptism. This was my call to prophesy. This was my call to purity of spirit. I was being called to take my stand with, and for, the oppressed.

And I wept because I knew where this kind of religion led Jesus and where it led Clarence Jordan, and where it led Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and where, in the fullness of time, it might lead me.

And I wept because I knew instinctively that if I preached the kind of God I had met on the shoulder of Interstate 64 west of Louisville, Ky., I was destined to disappoint. The words God spoke to Isaiah right after his “here am I, send me” profession took on a new meaning:

Go, and say to this people: “Hear and hear, but do not understand; see and see, but do not perceive.” Make the heart of this people fat, and their ears heavy, and shut their eyes; lest they see with their eyes, and hear with their ears, and understand with their hearts, and turn and be healed.

I preached some damn good sermons over the next 20 years, but my clever words fell lifeless to the floor and no one picked them up. And as I looked into the puzzled, disappointed eyes of my parishioners I would promise myself that, next week, I would preach a nice, uplifting sermon that people would praise because, damn it, I needed that!

But I could never make it happen. The words of the prophets would be lying right there in front of me. And I would reach down and pick them up.

I have always loved (and hated) the confession of Jeremiah:

If I say, “I will not mention him,

or speak any more in his name,”

there is in my heart as it were a burning fire

shut up in my bones,

and I am weary with holding it in,

and I cannot.

And I would preach yet another sermon about the God who stands with the poor and the outcast and people would stare at me like I was some kind of idiot.

So in 1998, when Nancy decided to follow her parents back to Tulia, Texas, I didn’t put up much of a fight. Nancy’s father, Charles Kiker, had been pastor of First Baptist Church in Kansas City, Kan., an exceedingly white congregation surrounded by an increasingly African-American neighborhood. Charles hired a promising young African-American preacher as his associate and started reaching out to the community. The outreach was so successful that Charles was forced into retirement. When you stand with the poor, pushback comes swiftly. Every time.

No sooner were we all settled in Tulia than an almost comically corrupt drug bust was announced in the local newspaper. “Tulia’s streets cleared of garbage,” the headline read. Almost all of the 47 adults arrested in the drug sweep were African American as were the 50 children orphaned by the operation.

And everyone cheered because the bad guys were off the street, except for Nancy and Alan and her parents, Charles and Patricia. We knew too much. We had studied under Henlee Barnett and Glenn Stassen and Paul Simmons and Bill Leonard and Frank Tupper and Frank Stagg. We knew too much about people like old Clarence Jordan who once explained why he called the crucifixion of Jesus a lynching:

Jesus was officially tried and legally condemned, elements generally lacking in a lynching. But having observed the operation of Southern “justice,” and at times having been its victim, I can testify that more people have been lynched “by judicial action” than by unofficial ropes. Pilate at least had the courage and the honesty to publicly wash his hands and disavow all legal responsibility. “See to it yourselves,” he told the mob. And they did. They crucified him in Judea and they strung him up in Georgia, with a noose tied to a pine tree.

The relevance of Jordan’s words to the “judicial action” unfolding before us was obvious … at least for those whose ears were attuned to the gospel of Jesus Christ.

So we started talking to the victims of the operation. We talked to their lawyers who freely admitted that their clients, though innocent, would never be acquitted by an all-white jury. Not here in Tulia.

So every Sunday evening, our home would be crowded with 40 men, women and children who had been victimized by the Tulia sting. We read letters from prison and wrote letters to prison. We plotted, taking our lead from the civil rights movement, as a police cruiser rolled back and forth in front of our home.

And we sang.

Leaning on the everlasting arms.

Like a tree planted by the water we shall not be moved.

This land is your land, this land is my land.

Go down, Moses, way down in Egypt land, tell old Pharaoh to let my people go.

We called ourselves the Friends of Justice.

Five years after his speech in Montgomery, King wrote one of those “How my mind has changed” pieces for the Christian Century in which he said this:

Perhaps the suffering, frustration and agonizing moments which I have had to undergo as a result of my involvement in a difficult struggle have drawn me closer to God. Whatever the cause, God has been profoundly real to me in recent months. In the midst of outer dangers I have felt an inner calm and known resources of strength that only God could give. In many instances I have felt the power of God transforming the fatigue of despair into the buoyancy of hope.

That’s how it was for us in Tulia. I never doubted that our cause would prevail. If we were wrong, God Almighty was wrong. Our struggle for justice in Tulia was as soul-destroying as it was successful; but God has never seemed so real or so beautiful.

Fifty years ago, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was gunned down at the Loraine Motel in Memphis, Tenn. Everyone was shocked, but no one was surprised. “Jerusalem, Jerusalem, you who kill the prophets and stone those sent to you.”

The death of a prophet never comes as a surprise; but it always comes as a challenge. The words of prophets like Martin Luther King, and Clarence Jordan, and Jesus of Nazareth do not die. In fact, the words of the prophets are scattered all over the floor of this old church, and the renovations of recent years have not disturbed them. They’re still lying there. And if we stoop down and scoop up some of those wonderful words of life the fire of Jeremiah will be kindled in our bones, God will become frighteningly and beautifully real, and, once again, we shall turn and be healed.