A good story creates an emotional bond with readers.

A visual can intensify the bond, but only if it fits. It has to reflect the story, and it has to help tell the story.

Stock photos are generic. They aren’t created for specific stories. That’s why they often fall flat or seem inappropriate. You may have even seen them used elsewhere.

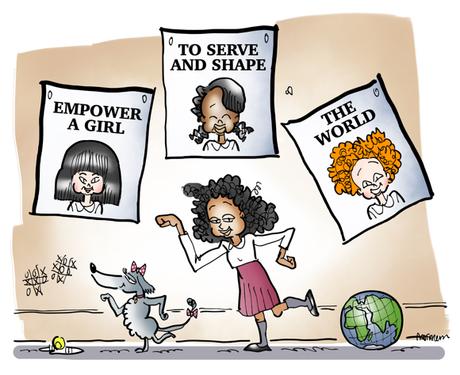

Custom illustration, by contrast, is created for a specific story. It enhances the text because it’s based on the text and tries to add another dimension to the story.

Read on for a good example.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I recently illustrated an essay titled, The Medically Misguided Approach To Mistreatment. The author is a anesthesiology resident looking back at her experience as a med student. You can read the entire essay here.

The term mistreatment refers to sexual and non-sexual harassment, prejudice, bigoted remarks and the like. The med school’s affiliated hospital had a mistreatment policy. That’s the subject of the essay.

The author writes that she was determined to achieve on the basis of merit alone, and that she “did not identify with being a woman of color, regardless of my South Asian heritage and femininity.” She begins by saying:

In 2013, I entered medical school, fresh out of the incubator of all-girls school education and liberal arts college. Given the bubble I grew up in—“empower a

girl to serve and shape our world” was emblazoned on posters in every single

one of my high school classrooms—it is safe to say that I had some unrealistic notions about the world.

She was asked to close an incision during an operation, something considered a great honor given that the medical student’s role during the surgical rotation is

not to touch anything.

My classmate relays that she was minimally supervised by a resident, but when

the attending surgeon returned to the operating room, displeased her sutures

could leave a deep scar, he said she “ruined the patient’s life forever.” My classmate did not report the incident, internalizing that the result of her inexperience was somehow her fault.

A resident is taking too long to complete an operation and the attending surgeon asks her if she’s menstruating, or on the rag, as though that would affect her surgical technique.

We are asked if this constitutes mistreatment. Yes, my group votes unanimously. What was offensive about the scenario? The usage of “on the rag,” my group

seemed to decide. The implication that women are somehow lesser surgeons for

an inherently female trait is lost to the group.

I decided to incorporate both situations– the one real, the other hypothetical– into a single illustration.

It is 2015. I am on my surgery clerkship and the course director asks each of us

what medical specialty we are thinking about pursuing. I have been warned about this question—it will later be on the list of things attendings cannot ask because of the students’ worry that their answer may influence their grade…

I defer answering, saying that I need to experience more clerkships before I can make a decision. This is known as a bullshit response. The attending tells me this

and then says he will guess which medical specialty is best for me. But I already know he is going to say Pediatrics.

Although the attending has never seen me act nurturing with anyone under the age of fifty (we are at a Veterans’ Affairs hospital), I am female, and therefore I belong with the children.

For our mistreatment seminar at the end of medical school, we are split into

groups based on our intended medical specialty. One student voices her concern

that this will decrease a diversity of opinions.

“Ugh, she must be going into peds,” my group mate says derisively.

“What’s wrong with peds?” I ask, knowing that I could have easily been that

student, having already been stereotyped as a future pediatrician.

“Too many feelings,” my group of future anesthesiologists jeers.