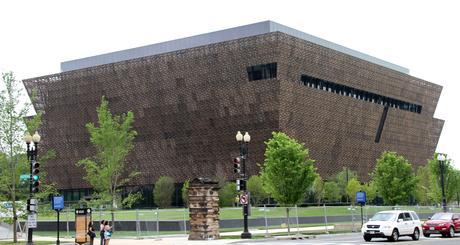

National Museum for African-American History and Culture

Two incredibly breathtaking, incredibly black things happened to me last weekend. First, I attended the TidalX1015 concert benefiting the Robin Hood Foundation. Then, I visited the newly inaugurated National Museum for African-American History and Culture (NMAAHC) in Washington, D.C. the very next day.

I had only found out that I would be attending the TidalX1015 concert and visiting the new museum a few days before my trip. A certain, relatively well-known teacher of mine was taking her radically experimental class to New York and DC to presumably learn about educational policy and black history. She invited me, her intern and mentee, to tag along.

But this certain teacher of mine loves a good surprise. She sent us the trip’s itinerary just two days before her class prepared for the rather grueling bus ride from Wake Forest University in North Carolina, to Brooklyn, New York. When I opened my email and found that I would soon be shouting the lyrics to “Feeling Myself” along with Nicki Minaj, as well as a slew of my other favorite artists, my cheeks ached from smiling. When I read that we would gain four-hour access to the incredibly booked NMAAHC the next day, my heart ached. I felt overwhelmed by the power of the opportunities we’d been granted.

Dr. Blair LM Kelley — a friend of my teacher, and an esteemed professor and leader at North Carolina State University — had been invited to be one of the first to walk through the halls of the Smithsonian’s monumental new ode to black history and culture. She wrote that the NMAAHC interweaves the tragedy and triumph of the black experience, rather than attempting to arrange itself chronologically from tragedy to triumph or characterize black history as one or the other.

I came to a similar conclusion as I moved from exhibit to exhibit, my raspy voice exasperated from the concert the night before and a quasi-republican, white Latina at my side (a story for another time). But I was also struck with the realization that my experience at the Tidal concert affected me similarly to how the new Museum of black history and culture did.

TidalX1015 was a kind of a living NMAAHC in the way that it, too, embodied both the triumph and tragedy of the black experience. The TidalX1015 artists were not just showing up on stage to jump, sing, and collect a check. They were showing up to support the Robin Hood Foundation, to support teachers with unnecessarily hard jobs who teach students with unnecessarily hard lives. Those students are overwhelmingly black. In fact, right outside the Barclays center, where the concert took place, and throughout New York City, 96 percent of black kids attend majority low-income schools. The audience that night was full of these hundreds of teachers who serve New York City’s high-need schools.

But I undoubtedly took the most away from Nicki Minaj’s performance. In many beautiful and tragic ways, Minaj’s narrative fits the same black canon displayed at the NMAAHC. As many fans know, the rap queen’s father was the victim of drug addiction and abused her and her mother for years. The man set her childhood home ablaze in a (thankfully) failed attempt to take the life of Nicki’s mom.

As Minaj blithely twerked to ‘Trap Queen’ by Fetty Wap minutes before Fetty himself appeared on stage, I imagined that she was shaking away the odds: Shaking away the shame that comes from the hyper-sexualization of black women, shaking away her demons. Nicki was then, and is often, strong, beautiful, and authentic as hell.

Minaj’s life could have easily gone another way. Her life could have paralleled Bresha Meadows, a black teenage girl who could face an adult aggravated murder charge for killing her own abusive father this summer — a father who terrorized her and her mother until Bresha felt his death was their only escape. Bresha may very well have been right about her dad: Black women are murdered by men two and a half times more often than white women, and half the time, spouses or partners are their killers. While Minaj overcame the odds stacked against her, the systems of patriarchy, misogynoir, and gun violence are too big and too strong for every individual to overcome through personal conviction alone.

But Minaj didn’t just serve as a unilateral emblem of feminist success that night. She also spoke about the power of women in a way that struck and confused me. “Barack needed a Michelle, Bill needed a Hillary—pray you don’t get stuck with a Melania [Trump],” she warned the men in the audience.

I loved the sentiment that behind the male figures who have been thrust into power have been women who could just as easily have filled their shoes. But I wondered why she had to put down another woman to say so. Minaj then drove this point home by going on one of her usual tirades against women she feels are beneath her—weak bitches, bum bitches, wack bitches, broke bitches, brainless bitches, Melania Trump.

I thought of this moment in particular while standing in the NMAAHC. While the museum took many opportunities to recognize the unimaginable strength of black people — of our athletes, of our minds, of our patience — those stories, and Minaj’s, are the exception, not the rule. And the expectation that we all should be “strong black women,” must strive to be this exception, may be killing us. In response to the trials of black womanhood, Nicki Minaj has chosen to survive by taking on the persona of those who have always held more social and political power — men. And she has to shit on the rest of us to do so.

As I watched Nicki, I was moved by her confidence. I always have been. I rushed to buy thigh high suede boots and an extra-long weave when I found out I was going to see her. I wanted to be as bad and fearless as her style and her songs. I admire her twisted self-actualization, her strength, her award-winning music and her fine-as-hell-ness (like, Minaj reminds me why I am queer.) She reminded me of all the victories black women have won: we’re at Apple Music being bad asses, we’re hitting the books harder than anyone else, and we’re even raising our daughters in the White House.

Unfortunately, Minaj reminded me of everything the intersections of white supremacy and misogyny have deprived of us, too. Being a black woman and a hip-hop fan is not always easy, but I take the insults and abuse from artists of all genders because hip-hop tells me the stories that are most important to me. It tells me them in ways I can shake to, in ways that make shiver, and in ways that make me mourn — just like the new Smithsonian National Museum of African-American History and Culture did.