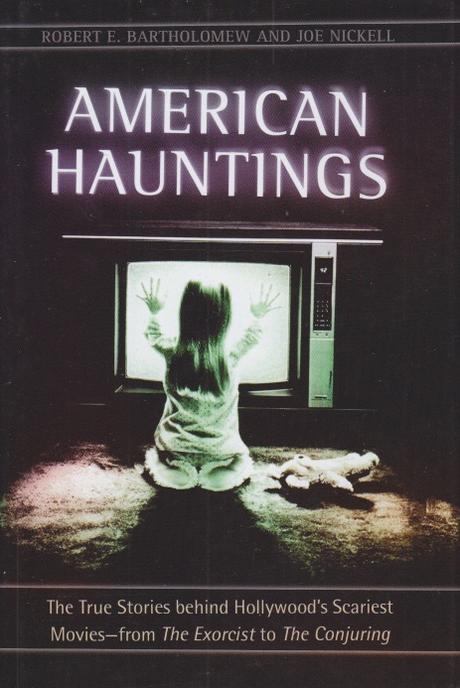

The thing about the unknown is that it’s, well, unknown. Like many people I’m interested in getting at the truth behind ghost claims, so American Hauntings: The True Stories behind Hollywood’s Scariest Movies—from The Exorcist to The Conjuring, by Robert E. Bartholomew and Joe Nickell looked helpful. Indeed, it is. To a degree. The book, however, devolves at points to debunking cases that aren’t in the movies and frequently asks “Why didn’t somebody take a picture?” (In cases where there are pictures they say how they could be faked.) Given the authors, you kind of know none of the claims will be accepted. Even so, there’s a lot of good information here. They do a great job of outlining the very probable hoax at Amityville. For some of the lesser known cases they offer explanations harder to believe than the poltergeists they so abhor.

That’s the thing: for all the “hauntings” they default to poltergeists and then explain how poltergeists are faked. They begin with An American Haunting, and move on to The Exorcist, Poltergeist, The Conjuring, The Amityville Horror, and The Haunting in Connecticut. Sandwiched in there is also the non-movie Don Decker case. What struck me as strange is they often seem offended that movies embellish stories. That’s what movies do. They’re quite right about the money aspect, however. They also take in films that make no claims about being true, such as Poltergeist, which drew inspiration from an actual case but didn’t make that assertion. It’s also odd that they didn’t ask some of the writers about this. I once met Brent Monahan, author of An American Haunting. He readily admitted some of it was made up. In other words, taking offense at the “based on a true story claim” feels a bit naive.

In some cases they speculate what might’ve happened without visiting the location. It’s hard to tell if a leaky roof can explain things when you don’t specify if the room is on the first or second floor. Also, suggesting a young boy is faking because a professional magician can duplicate effects raises its own set of questions. If a kid is as good as a professional, why doesn’t s/he go on the circuit and make some money from it? That kind of question, by the way, characterizes much of the skepticism in the book. Why not become a magician? Because we don’t have the whole story. It seems to me that dismissiveness doesn’t really help to get at the truth. Nevertheless, this book contains much that is useful and skeptical voices should always be included when attempting to sort our extraordinary claims, even if you never , ever want to be caught without a camera.