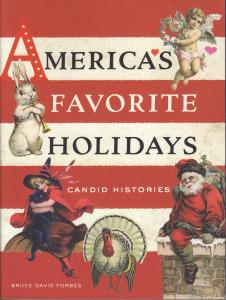

Time comes in different varieties. In temperate regions where the changing seasons keep the time of year for us, we tend to have seasonal holidays. Christmas and other December holidays mark the shortest days of the year with the hope that light will soon become more abundant. Spring rituals, near the time of the vernal equinox, encourage the return of fertility to the earth. Autumnal holidays mark the approach of darkness once again as the world twirls endlessly on. Summer, bright and warm, doesn’t really lend itself to so many holidays. These thoughts came back to me as I read Bruce David Forbes’s America’s Favorite Holidays: Candid Histories. Forbes doesn’t cover all the special days, but focuses on Christmas, Valentine’s Day, Easter, Halloween, and Thanksgiving. These are five holidays marked, in some sense, by spending. They are often, although Forbes doesn’t really spend too much time on it, the focal point of cultural wars where various Christian groups wish to reclaim a certain day for its “rightful heritage.”

Time comes in different varieties. In temperate regions where the changing seasons keep the time of year for us, we tend to have seasonal holidays. Christmas and other December holidays mark the shortest days of the year with the hope that light will soon become more abundant. Spring rituals, near the time of the vernal equinox, encourage the return of fertility to the earth. Autumnal holidays mark the approach of darkness once again as the world twirls endlessly on. Summer, bright and warm, doesn’t really lend itself to so many holidays. These thoughts came back to me as I read Bruce David Forbes’s America’s Favorite Holidays: Candid Histories. Forbes doesn’t cover all the special days, but focuses on Christmas, Valentine’s Day, Easter, Halloween, and Thanksgiving. These are five holidays marked, in some sense, by spending. They are often, although Forbes doesn’t really spend too much time on it, the focal point of cultural wars where various Christian groups wish to reclaim a certain day for its “rightful heritage.”

One of the real values of books like America’s Favorite Holidays is that it is clear that these claims of “keeping Christ in Christmas” and its kin are samples of collective amnesia. Many “Christmas” traditions predated Christianity. Others developed concurrent with it, but in “pagan” contexts. Christmas trees, for example, didn’t originate in the latitudes of Bethlehem. The same may be said for just about any holiday. Valentine’s Day and Thanksgiving, of the five explored, are the lone exceptions. These are fairly recent holidays and neither one marks a solstice or equinox. They celebrate aspects of life we value, making them sacred time. Don’t expect to get Valentine’s Day off of work, however. Capitalism never makes room for love.

Christmas, of course, is the holiday most under dispute. All holidays may be commercialized, but for Christmas spending is central. Forbes insightfully shows that Christmas is, and may always have been, both a cultural holiday and a religious holiday. The cultural aspect of the season is the one that most people celebrate. The birth of Jesus—which we are fairly certain was not in December—was a latter add-on. A baptism, if you will, of a pre-existing holiday. The winter solstice holiday is a staple of cultures in climes where the difference in available light and warmth is appreciable. It marks the point of the year when things start getting better. Yes, the real cold of winter has not yet set in, and there will be months of snow and ice. Still, once the solstice is passed, there is more light to help us cope. Celebrating sacred time, whether secular or not, is the natural reaction of people who crave light over darkness.