This program was supported by the same school superintendent that sent letters to parents calling for inclusion because she had received reports from staff that students have been repeating language they heard from presidential candidates in the media (mainly Trump). Looks like her “progressive” ways aren’t that successful.

From Seattle Times: When Jasmine Kettler kissed her mother goodbye at Sea-Tac Airport and boarded a plane to Bangkok last month, she carried nothing but a backpack, laptop and memories so traumatic that the former Highline High School teacher had purchased no return ticket.

Her plans are fluid. She may volunteer in a refugee camp on the Burmese border. She could spend a few months in a Thai monastery. The only firm agenda: healing from what she describes as three years of constant frustration and fear as a Highline teacher.

The pack-up-and-leave solution may be extreme, but Kettler is among more than 200 educators who had resigned from the district as of June, many saying Highline’s new approach to student discipline has created outright chaos.

The turmoil of the past school year didn’t help, with an alleged gang rape, several student deaths and criminal charges, including murder, for a group of boys not yet out of middle school. Six of the 19 homicide charges filed this year in King County have been brought against current or recent Highline students.

Veteran teachers are shaking their heads. Three years ago, Highline sat poised at the leading edge of a national effort to rethink the way schools handle misbehavior, based on evidence that booting kids out results mainly in their return to class angrier and more behind than ever — if they return at all.

Superintendent Susan Enfield

Superintendent Susan Enfield, an ambitious and visionary schools chief, vowed to eliminate such punitive sanctions, except in cases that jeopardized campus safety. Instead, Highline would keep its students on campus — even if they cursed at teachers, fought with peers or threw furniture — attempting to address the roots of their behavior through a combination of counseling and academic triage.

The outcry that has emerged since reveals a vast gulf between announcing ideals and making them real.

Early signs of trouble

Kettler, like many, initially thought Enfield’s progressive-minded approach was inspiring, even brilliant. The phys-ed teacher considered it a personal mission to help break the well-documented connection between sending kids out of school through old-fashioned discipline and seeing them end up in jail cells, a pattern known as the school-to-prison pipeline.

Across Lake Washington in Bellevue, similar concerns have spurred that district to spend an extra $160,000 this year on substance-abuse counselors and mediation training. Schools in Renton, Kent and Federal Way are experimenting with “restorative practices,” which fosters deep conversation between students and teachers.

But Highline has focused on in-school suspension. Rather than tossing kids for defiant behavior, teachers were expected to manage their outbursts in class, and refer chronic misbehavers to a kind of super study hall where an academic coach would get them back on track and connect those who needed it to counseling.

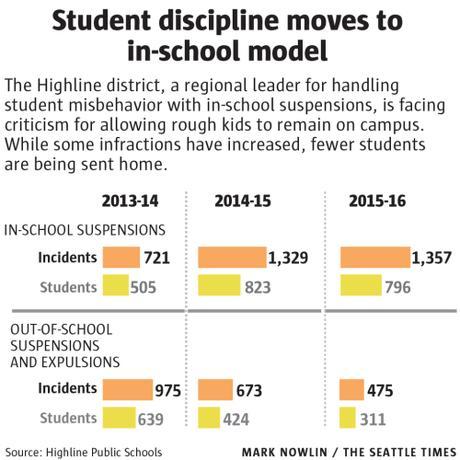

Over three years, from 2013 to 2016, expulsion and home suspensions in the district, which once totaled 2,100 incidents annually, plummeted 77 percent, to 475 last June, and Enfield began receiving applause throughout the region for her work on behalf of marginalized youth.

Data from Highline Public Schools

But in Highline classrooms, trouble cropped up immediately. Teachers had received little or no training on de-escalation techniques to use in their classrooms. Each school interpreted the new discipline rules differently. And in a district of 20,000 mostly poor kids, a single truancy officer was employed to ensure they attended class.

“I’ve never seen a kid come back from in-school suspension caught up,” said Kristina Smethers, an art teacher at Mount Rainier High. “In fact, they seemed to get worse, as if they really didn’t consider it much of a consequence.”

“Learning as we go”

Enfield acknowledges some missteps. It was a mistake, she said, to use the phrase “eliminate suspension” because the district always intended that principals would send kids home if they harmed staff or other students.

In-school suspension, she added, should not necessarily have been led by certified educators. But rather, people who could connect with kids. And classroom teachers could have benefitted from more training up front.

“We were kind of flying blind at first,” Enfield said. “I feel confident that we’re not giving suspensions for the wrong reasons anymore. Now we need to make sure what’s happening when they’re in the building is going right. We’re learning as we go.”

This year, she promises instruction for all educators on the effects of trauma, and how to defuse the explosive behaviors that often result. Simultaneously, those running Highline’s in-school suspension programs will follow up with kids to ensure they remain on track. Return visits will be seen as a red flag signaling the need for more serious corrections.

But overall, Enfield remains unapologetic about her belief that much of the responsibility for handling difficult students rests with teachers. “We are telling them, ‘You no longer get to write kids off.’ For some people, that’s been a struggle,” she said.

By way of example, she told the story of a seventh-grader who had cursed her teacher, pulled a hood over her head and refused to speak — all of it behavior that once would have resulted in a home suspension for defiance.

“What’s going on?” an assistant principal asked, after the girl was sent to the office.

For 20 minutes, the teen made no sound. Then a few tears dribbled down her face. She had been raped by her stepfather that morning, Enfield later learned. “What if it was three years ago and we had sent her home — back to that hell?” said the superintendent, tearing up herself. “I’d act out too if I was 13 and that was happening to me.”

Leaving in droves

Educators may be leaving by the score, but that also does not concern Enfield, who says turnover rates of 10 to 11 percent are standard in Highline.

Teachers union President Sue McCabe, however, sees those 200 resignations as evidence of a much deeper issue. This spring, 23 educators left Highline High School — almost 30 percent of the staff. Another 20 left Mount Rainier High, a quarter of the teaching force. This year, the entire science department at Global Connections High School is new.

“We have a morale problem,” McCabe said. “Rather than fighting for their students, or for themselves, people are leaving. Two hundred educators resigning — that’s a lot, no matter how ‘normal’ it is.”

Read the whole story here.

DCG