Remember this?

“What’chu lookin’ at, huh?”

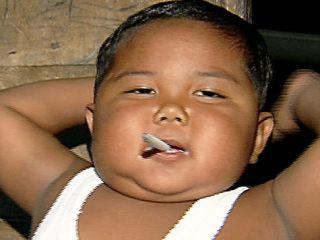

This ‘ere is our little friend, Ardi Rizal. He’s the Godfather of the Sumatran jungle, so ye better watch yerself if ye know what’s good for ya.

“Me no like your face”

A word of advice, never call the Boss small, shorty, little, or dwarf, he’ll skin ya alive and rip ye to shreds.

The Boss on his favorite truck. Red wunz go fasta!

Our Boss loves his small little truck and his little runts. Birds of a feather – hey! Who’re you people?! Hey! HEY! AaaAAaa!!!…………………….

“Ye call me small?”

In case you haven’t noticed, Indonesia is a nation of chimneys. No, not the ones attached to homes, I am talking about the kretek chimneys that dangle from the lips of a third of its populace. Indonesia is the Garden of Eden for Tobacco Inc. and one of its greatest wet dreams. While elsewhere around the world, tobacco consumption are seeing a gradual but definite fall, here in Indonesia, it continues to rise. According to Tobacco Free Center, as of 2010, there are over 80 million smokers in Indonesia. 63 percent of Indonesian men and 5 percent of Indonesian women puffs away every day. The Indonesian government have noted that the population of smokers have increased six-fold since the 1960s while cigarette consumption have seen an increase of 7 times since 1990 to some 250 Billion sticks of cigarettes in 2010. This makes Indonesia the third-largest consumer of tobacco by market size and its fifth-largest by volume of consumption.

The increase of tobacco consumption are exhilarating on the one hand. For Big Tobacco, Indonesia is a huge, lucrative and highly profitable market where they can expect the smoking population and frequency of consumption to continue to increase for the foreseeable future. Already, 29 percent of Indonesians aged 10 and upwards smoke an average of 12 sticks a day. Some 21 million Indonesian smokers are children between the age of 7 and 15.

It is not hard to see why smoking has grown in popularity in Indonesia, especially among the nation’s youth. Big Tobacco’s advertisements frequently portray hard boiled men climbing up huge cliffs or highly creative people and supermen doing impossible and improbable things. The message of those advertisements, which you can find aplenty across billboards and television, definitely help to endear tobacco to youths. Additionally, cigarette advertising also comes in the form concert sponsorship of local and international bands popular among youths. Such events are always accompanied by free cigarette packs giveaway to the audience, who can attend the concert for free. Additionally, there’s the cost factor, cigarettes can go for US$1 a pack or less than US$0.10 a stick. The affordability, popular advertising, cultural pressure to smoke as well as the general ignorance on the health effects of smoking made Indonesia one of Tobacco Inc.’s most lucrative market.

The upward trend of smoking, however, is also very worrying. It is already public knowledge in the developed world that cigarette smoke can cause various types of cancer. This has lead to widespread condemnation and state regulations to curb the sales and consumption of cigarettes. In Indonesia, however, such knowledge are hard to find. Beyond the doors of medical faculties of the nations’ universities as well as hospitals, the dangers of smoking is hardly known. In fact, the ignorance of the decades of scientific research on tobacco’s harmful health effects is so bad that there are clinics in the country that promote smoking cigarettes as a cure to cancer.

The numbers tell clearly the growing health impact of smoking. According to the latest data from the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, half of all Indonesian families can count at least one their members as smokers. Up to 97 million Indonesians are exposed to second-hand smoke at home. The NGO also counted 500,000 Indonesians who died from smoking-related illnesses each year. Other NGOs put up similar numbers, at least 400,000 smoking-related deaths annually, around twice the number of Indonesian deaths in the 2004 Aceh Tsunami. The harmful effects of smoking hit Indonesia’s poor hardest due to their inability to afford cancer treatment. And aside from the ramifications on health, they are badly affected in terms of economic well-being as well. According to a 2009 National Socioeconomic survey, Indonesia’s poor families spend 11 percent of their income on cigarettes. That’s more than 5 times what they spend on education and nearly 4 times what they spend on healthcare. Abdillah Hasan from the Demography Institute of the University of Indonesia (Universitas Indonesia) calculated that if a poor Indonesian family saved what they spend on cigarettes for 10 years, they could send a child to university or get themselves a decent home. Clearly, planning and prioritizing has gone to hell for the nation’s many poor.

So, with all these downsides, why aren’t the government doing something to seriously curb the consumption of tobacco? Two words that politicians always want more of answers it, jobs and taxes. Big Tobacco in Indonesia employs more than 360,000 people directly, mostly as factory hands rolling the country’s famed clove-spiced kretek cigarettes. Additionally, some 900,000 tobacco planters and 1.2 million clove farmers are dependent on the industry for their livelihood. With the scarcity of employment in Indonesia and the high levels of unemployment (and underemployment), any move to curb the industry will be faced with passionate opposition from not just the factory workers and the farmers but also legislators who count on these constituents for their votes. Additionally, tobacco is a big revenue generator for the Indonesian government, which collects more than Rp 57 Trillion (US$6.27 Billion) in excise taxes in 2010, some 10 percent of government revenue. Additionally, the industry is heavily involved in community programs, sponsoring sporting events, providing grants and scholarships to poor families and financial aid to small businesses.

The movement to curb tobacco consumption in the country will thus have to account for replacing the industry as an economic player. Otherwise, any effort will falter. For one thing, it is clear that while the Indonesian government takes in US$6.27 Billion in excise taxes from the industry, Indonesians spend some US$20 Billion in treating smoking-related illnesses annually within the last few years, nearly 4 times the government intake. The cost opportunity of that healthcare spending definitely offsets the potential losses in government revenue, which can be taken care of by shaving the size of government (and thus, spending). As for replacing the role of the industry as a huge employer, that would have to be done gradually though creating more jobs in other industries. Indonesia has plenty of potential for development and FDI inflows within the last few years and have been more generous than a decade ago. The government need only reduce red tapes (by reducing the size and responsibilities of government) and support infrastructure developments either through deregulation of infrastructure-building (allowing private enterprise into electricity-generation, road-building, railways etc) or public works, or both in order to turn the trickle of foreign direct and domestic investments into a torrent of capital. That would certainly be able to provide the economic conditions where the loss of the cigarette industry will not be missed, due to its reduced share in the economy and the availability of alternative employments.

Alas, as always, education will play a critical factor in cutting off the chain smoke. Indonesia does not need health fascists to create laws that banned cigarette consumption, no matter how just it might be. What Indonesia needs is an active advocacy and campaigns to inform and educate the populace on what they are dealing with. Anti-smoking advocates and NGOs should counter cigarette advertising with their own advertising. They should aggressively educate children and the communities through schools and community events. They should coordinate their efforts with other NGOs that deal with providing tangible social services and hitch on the goodwill as a platform for advertising the dangers of smoking. They should create clinics and health centers that can help people who wants to quit smoking, or work in partnership with existing clinics and hospitals for that. With enough advocacy and alternative choices to smoking (and supporting the tobacco industry), Indonesians would be inclined to kick the habit. In time, slowly but surely, cigarettes will become less popular and Indonesians can create a healthier and more productive society.

It might seem unjust to some that the cigarette industry, which has dedicated plenty of money to society by providing employment and donations for education and sports, should be targeted aggressively for annihilation, or at least significant reductions. However, do remember that all those good things they did, well, that’s just the smokescreen.