Helping children through grief can be difficult. Children need to understand death and be taught (through example and discussion) how to grieve properly so that they will (a) recover from the personal death they are faced with, and (b) learn how to grieve for when they are adults.

Helping children through grief can be difficult. Children need to understand death and be taught (through example and discussion) how to grieve properly so that they will (a) recover from the personal death they are faced with, and (b) learn how to grieve for when they are adults.

Children need different handling techniques at different ages, but the following guidelines will help as a general overview. If a 13 or 14 year old is faced with death she should be treated differently from a six year old. The older a child is, the more discussion centering on concepts can occur, but truthfulness is always a constant that should never be overlooked at any age.

Tell the child as soon as possible about the death.

Never delay the inevitable. It is best to tell the child about a death as quickly as you can. Otherwise, it will seem as if you are hiding something from the child.

Also, when you tell the child about a death, it helps if you can touch the child. Of course, how familiar you are with a child, or situation, will be your guide indicating how extensive the touching should be. Sometimes holding a person’s hand is enough to convey your care and understanding. Hugging demonstrates closeness, or with a young child, sitting on a lap offers security.

Always start the conversation with facts; something that the child knows. For instance, begin the discussion with: Remember when your mommy was going to the hospital for chemo-therapy every week? — or — Remember when the doctors said your mommy had cancer and your daddy told you?

Starting with factual information that a child would remember gives a solid foundation for the next step.

Be truthful.

Withholding the information is an additional threat to a child. By not telling a child how Uncle Hugo died, the adult makes the death even more frightening and less comprehensible.

Do not use euphemisms to label a death: Your father passed. (the ball? the potatoes?) –or– Aunt Katie expired. (Does that mean when the time expires on the meter, or my subscription expires, death will occur?) –or– He looks like he’s sleeping. (Your child may never sleep again!!)

Carefully explain what it means to be dead. Make sure the child knows that the dead never return. Explain what buried means, and if necessary, what cremation means.

Tell only the details the child is ready and willing to hear.

According to the Gesell Institute for Human Development, children at age seven are able to understand concepts, so before that age one should only use basic facts about a death. As the explainer, you want to actualize the crisis for the child (make it real) so that the child will be able to reprocess the information at each developmental level.

The parents will have to be willing and able to “revisit” the death when a child needs new information at each stage. If the death is mentioned four years later when the child is age 11, then new levels of understanding are being experienced and should be explored and discussed by the family.

Encourage the child to express his feelings.

Children are young adults and will go through many stages of grief just like “old” adults. The seven stages to look for when helping children through grief are:

1. Numbness: Just as the adults may go through a period of non-feeling, walking without thinking, doing by rote, a child can have the same reaction.

2. Alarm: This is a sense of danger that goes off in the child’s brain. It is especially true when a parent or sibling dies. Often, sleeplessness will occur.

3. Denial: Again, this is the same as the adult behavior. The child says, or believes, it didn’t happen; it couldn’t happen. If there is a lot of hyperactivity from the child, that is a sign that the child is denying what happened. A child may not be able to verbally express what he feels, so, he will express himself in a physical manner.

4. Yearning: This is a regression where the child wants the loved one back. The child may even say this aloud: I want Daddy back.

5. Searching: The child thinks a lot about the deceased. The child seems to be waiting for something to happen, like Daddy returning. There is a scanning of the environment. This can manifest itself by watching and listening to the news for the first time, keying in on items that deal with the same kind of death or accident.

6. Disorganization: You may see this in school work and social interactions. The child exhibits a lack of interest in work or does not get along with the same friends before the death.

7. Reorganization: The child consciously, or unconsciously, sets new guidelines for himself and his role in the family.

Take the child to the funeral.

Four elements occur when you take the child to the funeral:

a. Realization (Seeing is believing.)

b. Recall (They will be able to remember the death. It is more concrete evidence than just a statement that Uncle died.)

c. Expression (They are given the chance to express their grief.)

d. Support (They have a sense of support from others.)

If a person is already buried, take the child to the cemetery.

By taking the child to the cemetery the parent makes the child feel better because he has been included in the mourning process. This also gives the grief an object. Seeing where the loved one is buried increases the understanding and lessens the stage of disorganization.

Let the child tell others about death.

If a child is allowed to share his feelings about the death by talking to others, his anxiety is lessened which gives him a greater understanding of the death. It also lessens the anxiety because the child has more control over his emotions and reactions to the death.

If a child is too young to verbalize, it may be wise to have the child draw a picture. Many times children will express their feelings through drawings with great clarity without actually drawing a picture about death. Storm clouds, heavy lines and dark colors would show that the child is upset and needs to share his feelings aloud and perhaps with someone other than a close family member. Perhaps a teacher or friend would be the choice.

Encourage the child to talk.

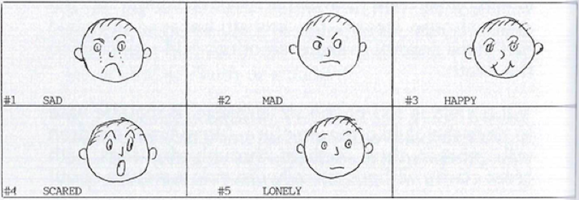

Always listen to what the child has to say. If the child seems reticent about opening up and discussing his emotions, use the “Five Faces” to help conquer this reluctance. Ask the child to look at the faces and tell a story about each face.

Questions to start a child thinking and talking could be some of the following:

1. Why is face #1 sad? What has made this face cry?

2. What made face #2 mad? Have you ever felt mad? When?

3. What is face #3 happy about? What makes you happy?

4. Face #4 is scared. What makes a person scared? Have you ever been afraid of something? What?

5. Why is face #5 feeling alone? What does “alone” feel like?

6. Which face is you right now? Can you tell me why?

Five Faces

Be available to answer questions.

No matter what you are doing, listen to the child. The question may not be as important as giving the child the recognition that his questions are important and he is important.

Never say: “Don’t feel that way.”

Comments like that, which are meant to be helpful, or at best meaningless, unintentionally do harm. It teaches children to repress their feelings, or “play dead” with their emotions. It also instills an incongruency which lowers self-esteem. By incongruency we mean that what a person feels on the inside is not manifested on the outside. As an adult he may become the confused stoic. Finally, it teaches them that the only way to cope in the adult world is through dishonesty.

As adults, we want to know the truth, to be encouraged to talk, or to be held when upset. Why should children be any different? Children also feel the need for support and the loss of the loved one. Adults must never lose sight of that fact. Nor should adults forget that it is their responsibility to teach the child how to grieve properly.

Think of the child as a smaller version of yourself. What would you want to know about the death? How would you like to be told? What questions would you ask? If you can keep this in mind, helping children through grief will be easier.

EXERCISE

1. Use the five faces to start the child talking about sadness, anger, happiness, fear and loneliness. Tell the child to make up a story about each face. Explain that the story does not have to have real people in it. (This is used to determine if the child is in touch with his feelings.)

2. Have the child draw a picture of the deceased as he remembered her (or him); or

Have the child draw a picture of himself; or

Have the child draw a picture about anything.

With each drawing have the child explain his picture to you, or make up a story to go with it.

3. If a child is older, one might ask the child to choose from the deceased’s possessions the one “thing” he would like to remember him/her by.

Ask why that item was chosen. (A vase because she always had fresh flowers. A picture that she painted or needlepointed. His paratrooper insignia and flight jacket.)

It is important to maintain discussion and open expression of feelings.

4. Ask the child to recount a story of the most memorable time he and the deceased spent together.

Canine, J. D. (1990) I Can I Will: Maximum Living Bereavement Support Group Guide. Birmingham, Michigan. Ball Publishers.