Recently I attended Science Climate Online, an “untraditional climate science conference” conference with journalists, government employees, nonprofit professionals, policy wonks, artists, activists and bloggers interested in climate science and creative approaches to communicating about climate change.

The takeaway was simple and reminiscent of William James’s famous saying, “Act as if what you do makes a difference. It does.”

Attendees, many of whom previously knew one another from the blogosphere and online world of Twitter, came hungry for fresh and novel ways to engage the public and readers.

Writer, blogger and professor Andrew Revkin opened the Science Climate Online conference with journalists, government employees, nonprofit professionals, policy wonks, artists, activists, bloggers and others touting the benefits of using the internet and online communities like Twitter to push information and to spread information in the age where news and storytelling never stops.

“Inventions, like (Twitter) hash tags, (see Science Climate Online’s #ScioClimate) are not just a solar panel. The potential to ‘show’ vs. ‘tell’ is huge,” he said. “They can build a sharing, shaping community.”

In 1985 Revkin wrote his first article about climate change, even before NASA scientist James Hansen famously testified on Capitol Hill in 1988 introducing and explaining the evidence of climate change to lawmakers. Today, he said, when climate change comes up in a conversation, “You can say ‘Oh my god,’ or you can decide how we make it work better.” He went on to emphasize the small part that everyone can play. “We need to play a part in making the planet a little less noisy and more productive.”

Even in today’s relentless information age where every day brings new scientific evidence, importance and impacts of climate change, he insisted, “…the surveys don’t matter, it’s getting people to care…climate matters and people care. The conditions you live in from year to year matter to you–too much water, not enough water, too much energy, not enough energy; where are the water and energy coming from?” He insisted that the details and the way in which we tell those stories are critical. “The Internet is the ultimate extension service and that’s what is exciting to me.”

Bob Deans, from the Natural Resources Defense Council, suggested that communicating about climate change is about knowing one’s audience and adapting the messaging. “It is vital that we meet people where they are…when people are willing to say ‘something is happening,’ then you have the basis to start the conversation. We are trying to build a national consensus for change. What matters is what you hear and what you remember when you walk out of the room.“

Deans asserted that the offer the importance of experiences in the stories that can be told to readers and audiences, like that of Louisiana, a politically conservative state that is understanding the importance of climate change because they are feeling its impact already. “The experiential piece is key. We have to put this in people’s backyards. Louisiana is the most conservative state in the country but Louisianans understand climate change because they have lost 1,900 square miles to sea level rise.”

Dean said, “Right now we have the best story ever with climate,” because the debate about its existence is over. But he also stressed that, “It’s got to be about me; we have to make it about them–’this is about your life, your family, your children.’” Now more than ever, too, he encouraged everyone attending to understand that each and every day and interaction is a chance to inspire thought and change amongst others. “Identity is the strong motivator in American politics–stronger than politics itself. There are 800 lobbyists that get up every day to get us not do anything.” Because of the political obstacles, Dean said there is a huge responsibility to the rest of us, “to stand up and say something in every chance we get.”

President Obama’s recent climate plan will not change everything but it will do something and we are going to benefit from this. “This is how we begin to talk about this issue,” Dean said. “People want to be good stewards of the planet, as our legacy as leaving something behind for one’s children.” He also credited Americans as being more concerned about climate change than they are often given credit. “The country is not divided, the politics is. Overwhelming around the country (in recent) elections, we went with candidates who are concerned and willing to shows their concern. We don’t want to be shrill. We want to be on point.”

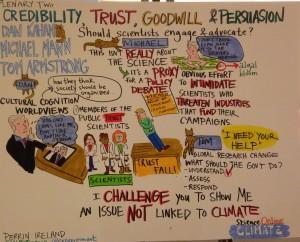

Ed Maibach, a professor conducting research with American Association for the Advancement of Science, “Triple A-S” (AAAS), spoke about the importance of using research to tell stories in the most effective ways. “Climate change scientists are shy about advocating for change. This simply isn’t the case with public health professionals and health issues.”

Maibach spent the first thirty years of his career in public health and in the last seven years shifted to work on climate change. His optimism was palpable.“I only started doing this research 6-7 years ago and I’m really excited because today the scientists are invited us to the table as opposed to years ago. We have to go do the research to be able to share the information with broader public.”

Science communication about climate change he said is “…is incredibly contingent upon my (and your) individual values. It is intensely personal. For me, the right decision is contingent upon what I’m most comfortable with.” He also said it is analogous to a team sport. “You need people playing different positions-strong, weak and opposition. We know that there is big myth in the U.S. that scientists disagree about the science of climate. So, how do we debunk that myth and change people’s prior understanding of that myth?”

Lisa Dropkin of Edge Research had one very simply solution to Maibach’s question. “Most of us don’t talk about [climate change] it because its awkward and hard.” She asked the audience, “how many of you talk to your neighbors about climate change?” She encouraged everyone to do this and committed to do so herself.

“We’re here to stop this shouting match.” The most important thing for anyone talking or writing about climate change she said is asking, ‘Who are we trying to convince to do what?’ Because communicating the facts of climate change or any other issue is never solely responsible for changing behavior. Rather it’s the facts and the metaphors and stories about why it matters that work.”

Lisa’s message resonated so strongly that during the closing session many individuals stood up to say their takeaways from the conference was the need to engage neighbors, friends and colleagues to talk about the concerns and solutions.

I could relate, too, as you probably can. After three years of researching and writing about Americans’ opinions and behaviors in the wake of the documentary “An Inconvenient Truth,” (for my master’s thesis) I started to hush my voice around family and friends who were not outwardly interested or concerned, especially with those whom seemed downright disinterested. Over time, however, I started to realize then that my research was losing its own impact because I wasn’t sharing it. What good are the causes and concerns that drive us, like climate change for me, if we leave them left only to be discussed with those already already concerned?

Therefore, I am dedicating this blog to all of you reading and thinking about your neighbors, family, friends and colleagues that you might consider asking about climate change, even those you would usually shy away from.

Josh Landis of Climate Nexus and CBS News who attended Science Climate Online offered an inspiring thought that I think might bring you confidence to go forth try this in whatever way you feel most confident. “Everyone needs to pluck their strings.”

So this weekend, if you haven’t yet ask a neighbor, “What do you think about climate change?” Their answer might surprise you.