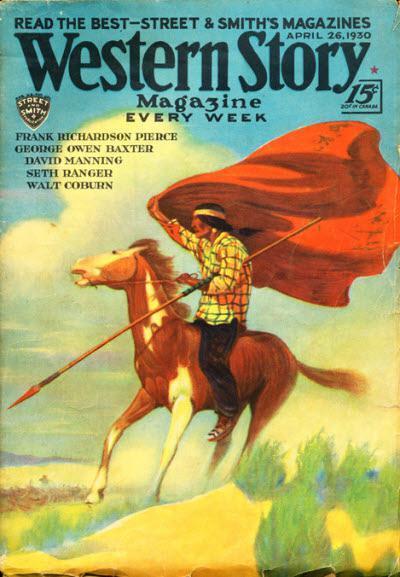

Book Review by George S: Happy Jack was published in book form in 1936, but it had first appeared in 1930, as a serial in Western Story Magazine, under one of Max Brand’s many pseudonyms, George Owen Baxter. Max Brand was itself a pseudonym. The author was born Frederick Faust, in 1892; other names he wrote under include: George Challis, Peter Dawson, Martin Dexter, Evin Evan, Evan Evans, John Frederick, David Manning, Peter Henry Morland, Hugh Owen, John Schoolcraft & Nicholas Silver.

Cover of the magazine that included the first installment of Happy Jack.

Cover of the magazine that included the first installment of Happy Jack.

He was an immensely prolific writer, and not just of Westerns. His Dr Kildare series of stories inspired a series of fifteen films in the thirties, and a very successful television series in the 1960s.

Happy Jack starts off on the ranch near Dabney Wells that is owned by the local lawman, Marshal Kinney. Jack Aberdeen is a carefree and light-hearted young man, who Kinney thinks hasn’t got what it takes to face the challenges of life. He discusses him with a visiting doctor, who disagrees, seeing in Happy Jack Aberdeen a young man with great but hidden potential. They make a bet and decide to test him. Jack owes eighty dollars to Charlie Lake, a mean gunfighter, and lake is coming to collect it the next day. Kinney steals the money from Jack’s bedroll, to see what will happen when Jack has to face Charlie Lake.

Lake is furious when his money is not forthcoming, and drives ‘a smashing blow against the face of Aberdeen with disastrous effect.’ To everyone’s amazement, holds his own in the fight, and Charlie Lake draws a gun – but Jack is quicker. He kills Lake.

As Marshall, Kinney arrests Jack for murder, though everyone agrees he should get off because Lake drew first. Jack is contemptuous, and bets Kinney that he will manage to get out of jail. He’s put in a ‘new-fangled cell’, constructed from a sheet of tool-proof steel.

When he is in jail, a crowd gathers, and Jack starts singing to them, a song insulting Kinney. The townsfolk combine to bust him out of jail. He takes Kinney’s horse and goes on the run, but not before he has stopped to speak sweet words to the girl Kinney wants to marry.

Then begins an epic chase, with Kinney dogged in pursuit and Jack making fun of him all the way. The story is taken up by the local newspaper, and Jack becomes a folk hero.

He falls in with Champ Logan, an older man who is a sort of Fagin figure, organising the local criminals to commit crimes. Jack likes Logan, but realises that the life of a criminal is not what he wants. Kinney tracks him to Logan’s hideout in the marshes, though, and they escape together.

It’s a story of wide open spaces and strong passions. According to a biography on the official Max Brand website, his favorite author was Homer, and there is a touch of the Homeric in the long pursuit over difficult country, the daring of Jack, and the chapter towards the end when the two opposites come face to face, man-to-man. That chapter is called ‘When Greek meets Greek.’ The book is set in the mythical West, and the action ranges from near Mexico to the Canadian border. No date is specified, but it’s maybe 1880s or 1890s. There are newspapers printed on hand presses, and there is talk of the railway, but that hasn’t reached anywhere near Dabney Wells yet. It’s at a point where the code of the West meets modernity and the rule of law.

At the end, the law wins out, and Jack is tried and convicted, but a message from the Governor brings him a pardon, because popular sympathy is on his side – like the sympathy of the reader, who very much does not want to see him shut up in prison.

I think the appeal of a western story in the thirties would mostly be because it’s a rattling good yarn. Partly, though, the appeal is nostalgic, as it shows a mythical simpler world that is fast vanishing. It’s a world where the cowboy’s song frees him from the modern high-tech cell. It’s a very male world. The one female character, Kitty, is just there to be the girl that both men love. The deep emotions are in the friendship of Jack and Champ, and in the obsessive enmity (in excess of the circumstances) between Jack and Kinney. It’s also working-class fiction, working through the conflict between authority and the individual. There was a huge market among British working-class males for Westerns, as for American crime fiction. Both gave a picture of a more democratic society, where traditional male values stood for more than social graces or class position. This book is fairly typical in enlisting our sympathy in favour of the lone individualist farmhand against the wealthy rancher. It’s a liberating read, and I thoroughly enjoyed it.

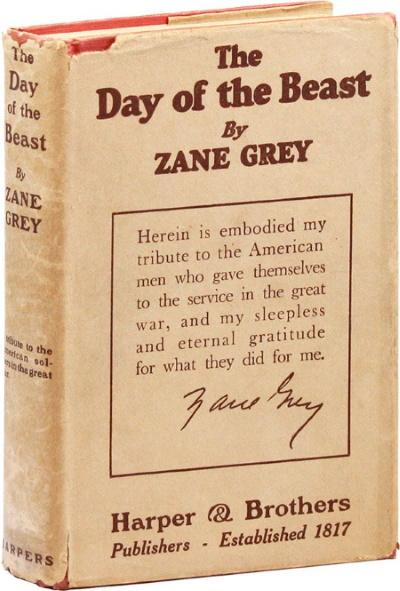

By the way – with this being Westerns month at the Sheffield Hallam Reading Group, I started off by reading a couple of books by the most famous of Western writers – Zane Grey. But I found books by him that related to my main popular fiction interest – fiction about the Great War, so I blogged about these on my Great War Fiction website. The Desert of Wheat is a 1919 novel about German-Americans facing a conflict of interests when America declares war on Germany. The villains are trade unionists who spread discontent among the farm workers (their efforts financed by German agents). The Day of the Beast (1922) is about a soldier returning from the war, and being disgusted by the immorality of postwar society. It reminded me of Warwick Deeping at his most sententiously disapproving. Max Brand’s book beats these hollow.