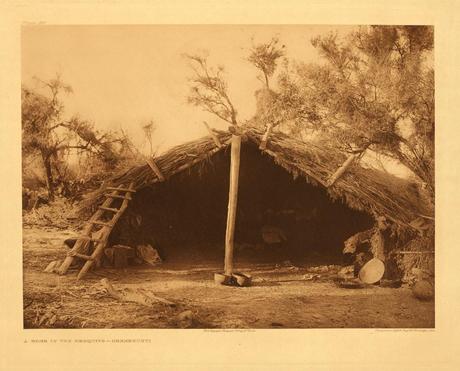

Some years ago I acquired a folio or large-sized Edward S. Curtis photogravure titled “A Home in the Mesquite — Chemehuevi” (1924). Here’s the image:

This surely sounds strange, given that Brownville sits in the verdant Missouri River Valley of southeastern Nebraska. It’s a long way – roughly 1,100 miles as crows fly – from the Mojave Desert homeland of the Chemehuevi. Distance aside, the two landscapes could not be more different. Nebraska’s eastern edge is an ecotone or transitional zone where hardwood forests and prairies give way to the Great Plains proper. The Missouri River, running north-south along this edge, bisects a borderland consisting of a miles wide flood plain, loamy alluvial bottomlands, densely wooded valley bluffs, and tall grass prairie uplands. Moving west out of the valley, the trees thin and the land begins a slow majestic roll into the vast grasslands and endless vistas of the central Great Plains. Up until 150 years ago, these grasslands supported the largest concentration of large mammals (i.e., bison, elk, and antelope) on earth, surpassing even the great ungulate herds of Africa. It’s stunningly beautiful and rich country that has attracted Native Americans for at least 12,000 years, having been occupied most recently by the Omaha, Oto, Ponca, Ioway, Kansa, and Pawnee tribes.

All of which is to say that this lush ecotone is not just a thousand crow miles from the Mojave Desert: these are world’s apart. The Mojave, while beautiful in its way, is stark and even forbidding. It’s not a land, or landscape, which says bounty or signals home. Yet the Chemehuevis and their southern Paiute brethren chose it for home and have made it their home for thousands of years.

At this point, you may be wondering how I discovered the Chemehuevi in Brownville. Those who ever visited Omaha’s Old Market may recall, fondly I would guess, The Antiquarium Bookstore and its wonderfully polymathic owner, Tom Rudloff. After visiting the famous Shakespeare and Company bookstore back in the 1960s, Tom decided that Omaha needed what Paris had. Over many years, Tom turned The Antiquarium into something every bit as good and in some ways better. The Antiquarium was an Omaha institution, its gathering place for artists, oddballs, intellectuals, writers, and nomads. In 2007, Tom broke Omaha’s heart by picking up and moving the whole thing (including over 100,000 books) to Brownville, where he had just purchased an old school to house the books and art. It’s a charming red brick WPA-style structure from the 1930s that sits in the middle of an artisan’s community. In other words, it’s perfect. This explains why I was camping in Brownville, at The Antiquarium, for several days.

One night, while having wine and picking Tom’s brain about Native American ethnography, he asked me what I knew about the Chemehuevi. Nothing, I had to confess, other than the fact I had a Curtis gravure of a Chemehuevi home hanging on my wall. He then told me about Carobeth Laird and her books, which he considered to be masterpieces. Coming from Tom, this is no small praise. Laird’s story, a hint of which appears in this 1983 obit from the New York Times, is remarkable. But her books, which Tom happened to have hidden away in his Rare Book Room, are even more remarkable. They now sit on my shelf, having been read in short order upon my return.

Laird’s most famous book, or the book that made her famous, is Encounter with an Angry God: Recollections of My Life with John Peabody Harrington (1975). Harrington, for those who don’t know, was an anthropological savant and linguist who spent 40 years of his life obsessively gathering ethnographic data on several little-known and fast-disappearing Native American societies in and around southern California. His salvage work was so prodigious that it weighs in the tons and now occupies 700 hundred feet of shelf space at the Smithsonian. Much of it still awaits the army of PhD students needed to digest and present the materials in organized monographs. Harrington was, in a curious and brilliant way, like Edward Curtis: he devoted his entire life to an enormous and quixotic project. Those who engage in these kinds of epic quests usually suffer, as do those around them. Laird lyrically and sympathetically captures all this in Encounter with an Angry God.

While Angry God is justly famous, in my estimation it pales in comparison to Laird’s simply-titled ethnography, The Chemehuevis (1976). This is indeed, as Tom said it was, a masterpiece. Its most remarkable feature is one I hardly expected but might have guessed: the Chemehuevis, having lived in the Mojave for perhaps thousands of years, developed a worldview that has much in common with Australian Aborigines, especially those (such as the Arunta) living in the central desert. In both settings, landscapes are all-important and song-trails are used not just for navigation but also for successful adaptation to these harsh and unforgiving environments. For both the Chemehuevi and the Arunta, lands, songs, trails, dreams, water, plants, and animals are all woven together, ritually and mythically, into worldviews that make sense and enable life.

Having said all this, I can now say that the Curtis gravure of the Chemehuevi home hanging on my wall is now among my favorites. I will have more to say about Laird and the Chemehuevis in the future, but I wanted to share this straightaway so that those interested can start reading.