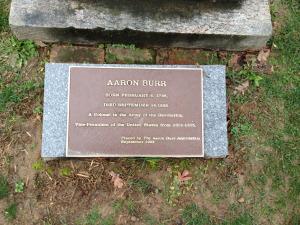

Religion and politics. It’s difficult to get over the wisdom instilled in your earliest years, and I was one of those who learned that religion and politics always cause potential friction in polite conversation. They are both, however, very important to people and knowing how to communicate about them irenically is a sign of maturity. While I can’t afford Broadway shows, I have read reports about the brilliance of a couple shows that feature—what else?—religion and politics. “Book of Mormon” has continued to be a success in the theater district, and, starting this summer, “Hamilton” joined the ranks of most popular Broadway shows. A hip-hop-inspired version of the story of Alexander Hamilton, the show offers history to audiences traditionally just out for a good time. I haven’t seen the show, but on a recent long car ride, I listened to the soundtrack and I have to admit that I haven’t stopped thinking about it since. Part of the reason is the sadness of the story—the dual between Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton ended up with one of the “forgotten founding fathers” dead, and another cast forever as a criminal.

Although my interest in history has defined my career (such as it is), I don’t pretend to know much about the revolutionary period. One of the reasons is that I’m more than a bit ashamed by the treatment of American Indians by the colonials. It is hard to celebrate when you feel like a criminal yourself. Another reason has been that ancient history has always captivated me, and events two-to-two-and-a-half centuries ago feel too recent. Nevertheless, I find myself in New Jersey where much of the Revolution played out: Washington crossing the Delaware, the Battle of Princeton, the Battle of Monmouth, and many other famous episodes. The British of that time enjoyed the power of empire—keeping others down so that the privileged might see themselves entitled. In the musical, King George has a role, in my mind, similar to Pontus Pilate in Jesus Christ Superstar.

I can’t help but think that what Lin-Manuel Miranda has offered in “Hamilton” is an extended kind of parable. The show is noted for its multi-ethnic cast in a story that was almost entirely, historically speaking, one of white privilege. Who can hear the songs swirling around the shooting of Hamilton and not think of the equally insane shooting of young African Americans who, like Hamilton, have no intention of causing harm? There are writers and poets and lovers who still try to find their place in a country that bathes the uber-rich with adoration and tax breaks and far too much power. “Hamilton” may, if people actually pay attention, turn out to be revolutionary. Politics and religion share that feature in common.