By Alan Bean

By Alan Bean

“Guns don’t kill people,” David Cole says, “indifference to poverty kills people.”

So long as the consequences of gun violence are born by poor black males, Cole believes, the nation will not pass meaningful gun regulation laws.

There are two obvious responses to Cole’s argument. It has frequently been noted that most of the cities with high rates of gun-related homicide already have strict gun control laws. But this only underscores the need for national legislation that discourages people from importing guns into urban neighborhoods.

The second quibble is even more obvious: if poor black males are using guns to kill one another that’s on them. The only solution, this argument goes, is for young black males to use firearms more responsibly.

This is where Cole’s argument gets interesting. High rates of gun violence, he argues, are a function of unemployment and all the other social ills afflicting folks who occupy the lower rungs of the social ladder. Ergo, you can’t stop gun violence without addressing poverty.

In Don’t Shoot, David Kennedy takes issue with Cole’s thesis. If we have to fix every social problem before gangs stop shooting, he says, progress is impossible. The important thing is to get gang members, community leaders in poor neighborhoods, and the police talking to one another.

In many ways, Cole’s analysis parallels the position Adam Winkler stakes out in his book Gunfight. Both gun control laws and a passion for Second Amendment rights have historically been driven by a fear of young black males with guns. First we want to restrict the ability of the black guys to obtain and carry weapons. Then we want to arm ourselves to the teeth to protect ourselves from young black males with guns. The problem, as I have previously noted, is that the young men doing most of the shooting restrict their violence to the folks living within a mile or less of home. And that, Cole says, explains our inability to to confront the issue of gun violence.

Cole and Kennedy agree on one essential point: we can’t come to grips with gun violence until we are ready to take an objective look at poor urban neighborhoods. And that’s what we refuse to do.

As things stand, the good people at MSNBC and FOX are talking past each other. Commentators at FOX speak for gun-toting white people determined to keep dangerous minorities at bay. MSNBC pundits routinely ignore the fact that, mass killings notwithstanding, gun violence is largely restricted to poor minority neighborhoods. One side supports 2nd Amendment rights, the other favors strict gun control legislation, but no one makes a distinction between mass killings like Newtown, and the routine slaughter on the mean streets of Chicago.

I favor Kennedy’s approach because it stresses honest communication. When gang members, community elders, and police officers are forced to really listen to one another things change. But, as Cole suggests, we can’t take this approach until we stop demonizing poor people.

Who Pays for the Right to Bear Arms?

By DAVID COLE

Published: January 1, 2013

IN the days following the Newtown massacre the nation’s newspapers were filled with heart-wrenching pictures of the innocent victims. The slaughter was unimaginably shocking. But the broader tragedy of gun violence is felt mostly not in leafy suburbs, but in America’s inner cities.

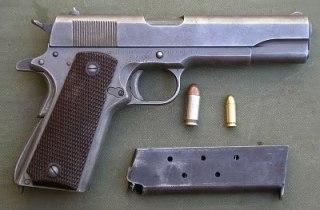

The right to bear arms typically invokes the romantic image of a cowboy toting a rifle on the plains. In modern-day America, though, the more realistic picture is that of a young black man gunned down in his prime in a dark alley. When we celebrate gun rights, we all too often ignore their disproportionate racial burdens. Any effort to address gun violence must focus on the inner city.

Last year Chicago had some 500 homicides, 87 percent of them gun-related. In the city’s public schools, 319 students were shot in the 2011-12 school year, 24 of them fatally. African-Americans are 33 percent of the Chicago population, but about 70 percent of the murder victims.

The same is true in other cities. In 2011, 80 percent of the 324 people killed in Philadelphia were killed by guns, and three-quarters of the victims were black.

Racial disparities in gun violence far outstrip those in almost any other area of life. Black unemployment is double that for whites, as is black infant mortality. But young black men die of gun homicide at a rate eight times that of young white men. Could it be that the laxity of the nation’s gun laws is tolerated because its deadly costs are borne by the segregated black and Latino populations of North Philadelphia and Chicago’s South Side?

The history of gun regulation is inextricably interwoven with race. Some of the nation’s most stringent gun laws emerged in the South after the Civil War, as Southern whites feared what newly freed slaves might do if armed. At the same time, Northerners saw the freed slaves’ right to bear arms as critical to protecting them from the Ku Klux Klan.

In the 1960s, Huey P. Newton and the Black Panther Party made the gun a centralsymbol of black power, claiming that “the gun is the only thing that will free us.” On May 2, 1967, taking advantage of California’s lax gun laws, several Panthers marched through the State Capitol in Sacramento carrying raised and loaded weapons, generating widespread news coverage.

The police could do nothing, as the Panthers broke no laws. But three months later, Gov. Ronald Reagan signed into law one of the strictest gun control laws in the country.

The urban riots of the late 1960s — combined with rising crime rates and a string of high-profile assassinations — spurred Congress to pass federal gun control laws, banning interstate commerce in guns except for federally licensed dealers and collectors; prohibiting sales to felons, the mentally ill, substance abusers and minors; and expanding licensing requirements.

These laws contain large loopholes, however, and are plainly inadequate to deal with the increased number and lethality of modern weapons. But as long as gun violence largely targets young black men in urban ghettos, the nation seems indifferent. At Newtown, the often all-too-invisible costs of the right to bear arms were made starkly visible — precisely because these weren’t the usual victims. The nation took note, and President Obama has promised reform, though he has not yet made a specific proposal.

Gun rights defenders argue that gun laws don’t reduce violence, noting that many cities with high gun violence already have strict gun laws. But this ignores the ease with which urban residents can evade local laws by obtaining guns from dealers outside their cities or states. Effective gun regulation requires a nationally coordinated response.

A cynic might propose resurrecting the Black Panthers to heighten white anxiety as the swiftest route to breaking the logjam on gun reform. I hope we are better than that. If the nation were to view the everyday tragedies that befall young black and Latino men in the inner cities with the same sympathy that it has shown for the Newtown victims, there would be a groundswell of support not just for gun law reform, but for much broader measures.

If we are to reduce the inequitable costs of gun rights, it’s not enough to tighten licensing requirements, expand background checks to private gun sales or ban assault weapons. In addition to such national measures, meaningful reform must include initiatives directed to where gun violence is worst: the inner cities. Aggressive interventions by police and social workers focused on gang gun violence, coupled with economic investment, better schools and more after-school and job training programs, are all necessary if we are to reduce the violence that gun rights entail.

To tweak the National Rifle Association’s refrain, “guns don’t kill people; indifference to poverty kills people.” We can’t in good conscience keep making young black men pay the cost of our right to bear arms.

David Cole is a professor of constitutional law and criminal justice at the Georgetown University Law Center.