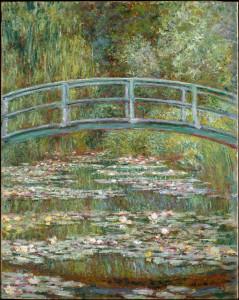

Mike Siegel has been a regular and faithful reader of this blog for at least five years, and has on numerous occasions assisted me with scientific or other issues. See, he’s a professional astronomer and a blogger himself, and now he’s a fiction writer as well; last week, he self-published his first novel through Kindle Direct Publishing. The book is entitled The Water Lily Pond after the series of Monet paintings that inspired it. He synopsizes it thusly: “Many decades in the future, medical science has made aging a thing of the past. Painter Walter Winston, at age 128, finds himself dying from simply being exhausted from life. He sets off on a journey to revisit the places he’s lived, trying to rediscover himself, his life and the people who made it worth living. It’s science fiction, yes. But it’s not really about science. It’s about time and old age and regret and art…The two passages below take place after Walter’s wife has died. Having been alone for a long time and wanting to avoid complications, he occasionally hires an escort. On at least one occasion, a university hosting his lecture hired an escort for him. The first passage concerns the latter“:

The last time he’d been in a hotel room identical to this one he had not been alone. She was a pretty girl from Ecuador whom the University had arranged for him. He was a hundred years older than her. They had lain in bed after it was done — the school had generously paid for the entire night. He thought of David and Abishag in the Americo painting. They had sent her to warm him.

The last time he’d been in a hotel room identical to this one he had not been alone. She was a pretty girl from Ecuador whom the University had arranged for him. He was a hundred years older than her. They had lain in bed after it was done — the school had generously paid for the entire night. He thought of David and Abishag in the Americo painting. They had sent her to warm him.

Her cigarette smoke made lazy curls on the ceiling as she talked to him. She was certainly the smartest girl he’d ever had – she spoke four languages and was earning her degree from UCLA in astronautics. She spoke of a future on the Earth-Moon run.

“Why do you do this, then?” he’d asked, shocked.

She stared at him for a moment then giggled.

“You’re so old-fashioned.”

“I’m so old!”

“It’s endearing. I think the oldest man I’d been with before you was … 90? 95? He wasn’t quite as prudent.”

“You didn’t answer the question.”

She rolled over, her black hair spilling onto the white pillow like a Pollock painting, her hip making a steep curve beneath the sheets like a Reubens. It made him feel a lot younger than 125 to look at her and to touch her.

“I enjoy it. It’s that simple. The money’s great. I certainly wouldn’t do it for free. But mainly I enjoy it. Not the act, per se. I enjoy the people. I always get high-class clients. Like famous artists,” she said, poking him in the belly.

He sank against the pillow, wondering if he was the only person on Earth old enough to see any stigma in her job.

“Do you remember everyone you’ve ever been with?” she asked. “After …”

“After all this time?” He grinned and nodded. “Sometimes it takes a while, but I do. Not that I’ve been with that many.

“It’s not just women I’ve been with that I remember. I can remember women I’ve wanted and never had. I can still remember a girl I passed on the street a century ago. She had the deepest eyes I’d ever seen. A short white skirt and a green blouse. She’s probably been dead half a century; certainly never knew my name or who I was. And yet I think about her. I can still see the fabric of the blouse clinging to her body.”

She leaned over and kissed him. “You should have painted her.”

“I did.”

This next passage is from a bit later in the book and references the time Walter lived in the worst part of Harlem in the 1980’s as a struggling artist.

He had never hired a professional before Sarah was gone. Even in his loneliest nights in Harlem, shortly after his marriage with Anna had collapsed, when he could hear the streetwalkers and their clients in the alleys and crack houses of the neighborhood; when he couldn’t walk to and from home without at least a couple of them asking if he wanted a date. It had never really crossed his mind.

“They didn’t repel me,” he told Sarah once. “I got to know some of them over time. Most of them were nice enough and a couple even knew about my art. I even drew inspiration from them for one or two paintings.”

“They were in the pentaptych,” said Sarah.

“One was. A woman who doggedly worked a corner near me for almost a decade. Put her kid through school on it. But I just wasn’t interested in what they were offering.”

It was Chuck who talked him into it. Chuck, who knew that the side of the industry Walter had seen in King’s Slate was the bad part of a much larger enterprise.

“You should come with me to Vegas,” he said one night at the lake, three years after Sarah had died. There had been an awkward discussion over dinner about whether Walter should get “out there” or not. Now he and Chuck were on the dock, in the darkness.

“Or up to Toronto. Or over to Paris. Or Bucharest. Or anywhere. Any sophisticated city is going to have professionals – talented, beautiful. Most places, you wouldn’t even be breaking the law anymore.”

Walter shifted uncomfortably in his deck chair. The water lapped quietly under the dock.

“Look, I know how you were raised. But at our age … do you really want to date? Do you want to go through that? Especially with two grandchildren and another on the way? What are you going to do if you meet someone? Move away? Leave little Lucia all by herself? This is a way to not be alone but not have complications.”

“I just can’t see myself doing that,” said Walter. “Paying someone to pretend to be attracted to me? It’s not like there’s a shortage of art fans or anything, if meaningless sex was what I wanted.”

“But a professional won’t stalk you. She won’t want to get pregnant. She won’t tell everyone about it. And it’s not just sex. Sometimes it’s not even sex. I hired a woman in Moscow to basically go to the Bolshoi with me.”

“Can we just let it go?”

Chuck shrugged. “As you wish. But men our age have needs. Yours will get the better of you at some point. Less risk if it’s a professional than an amateur.”

In the end, Chuck was right. He had been surprised that it wasn’t the sex itself that made him happy. It was the touch of skin, the rustle of sheets, the play of light on a naked body. It was the feeling, however faintly, of being back in those sepia and ash-colored days when he and Sarah or Juliette or Anna or Linda would lie in a warm bed and just enjoy not being alone.

“Intimacy,” said Chuck. “Companionship. Remember Abishag.”

It wasn’t often – a few times a year, maybe. But it was enough to get through the previous four decades.

Mike writes, “I didn’t set out to reference sex work in my novel. It just seemed like what the character would do, given his arc, and I saw no reason to shy away from it. Sex work is a part of our world and will continue to be a part of our world long into the future. There’s no point in pretending it doesn’t exist.” Mike is a great guy, an ally of sex workers and a friend; if you enjoyed these excerpts, you really ought to consider buying his book. Pretty please?