Jeremy Malcolm is the founder and director of the Prostasia Foundation, the first sex-positive and pro-civil rights child protection organization. He’s an IT and intellectual property lawyer and consultant, and a member of the Multistakeholder Advisory Group of the United Nations Internet Governance Forum; prior to Prostasia he was Senior Global Policy Analyst at Electronic Frontier Foundation. When he asked me to be on Prostasia’s advisory council I gladly accepted, and when it came time to start getting the word out I naturally offered this space.

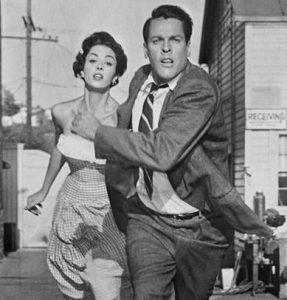

As a child, I remember how terrified I was by a rerun of the 1956 movie Invasion of the Body Snatchers, in which the lead character attempts to sound the alarm about a stealth alien invasion of Earth. In the final scene of the movie, mounting panic overcomes him as realizes that he is too late, and that the vehicles passing him by on the roadside are already carrying the alien pods that contain the seeds of humanity’s doom. The movie was widely interpreted as a cold war allegory, because it reflected how the public fear of infiltration of the United States by communists had been worked up into such a frenzy by Senator Joseph McCarthy that it empowered the government (for a while) to get away with taking repressive measures in response—measures that would never otherwise have been considered justified outside of wartime. Although the red scare has passed, the public feeling of creeping terror about existential threats to our society, and the shrewd and calculating management of that feeling, remains part and parcel of contemporary politics today. So much so, that international relations scholars have a specific a word used to describe what happens when governments manipulate public fear in this way: it’s called securitization.

As a child, I remember how terrified I was by a rerun of the 1956 movie Invasion of the Body Snatchers, in which the lead character attempts to sound the alarm about a stealth alien invasion of Earth. In the final scene of the movie, mounting panic overcomes him as realizes that he is too late, and that the vehicles passing him by on the roadside are already carrying the alien pods that contain the seeds of humanity’s doom. The movie was widely interpreted as a cold war allegory, because it reflected how the public fear of infiltration of the United States by communists had been worked up into such a frenzy by Senator Joseph McCarthy that it empowered the government (for a while) to get away with taking repressive measures in response—measures that would never otherwise have been considered justified outside of wartime. Although the red scare has passed, the public feeling of creeping terror about existential threats to our society, and the shrewd and calculating management of that feeling, remains part and parcel of contemporary politics today. So much so, that international relations scholars have a specific a word used to describe what happens when governments manipulate public fear in this way: it’s called securitization.

When a public policy issue is not merely politicized, but securitized, it is constructed in such a way that authorities assert the right to take extraordinary and otherwise impermissible measures in response. Whatever the issue happens to be—it might be terrorism, ebola, or migration, for instance—if politicians are able to whip up enough hysteria about the threat that it poses to the integrity and long-term survival of a society, concerns about human rights, public debate, and due process can be hand-waved away. Too much is at stake—our lives, our liberty! And very often too: our children. So it is that we often observe this pattern of rhetoric when child protection laws are put forward. It is quite right that we should do all that we can constitutionally do to protect children from sexual abuse, and that the political process should be a part of this. It’s also normal that politicians will selectively use the evidence that supports laws that they favor. But a healthy political process is one in which that evidence is at least open for debate, and in which the effects of proposed laws on our rights and freedoms as a society are carefully scrutinized. These democratic safeguards are frequently bypassed when it comes to child protection laws, because of how child sexual abuse is securitized, framed as an existential threat that has to be purged from society at any cost. This construction of the issue transforms Congress from what should be – a sober, deliberative legislative body (a filter for the views of the people, as Alexander Hamilton would have it) – into a mirror of a society in moral panic, willing to accept with a minimum of scrutiny almost any measure that purports to address the problem.

Proponents of such laws know this full well, which is why they invest heavily in fueling and manipulating the moral panic that gives child protection this privileged status in political discourse. One way in which they do this is by playing on emotions, rather than evidence—and since child protection involves very strong emotions anyway, all that might be needed to push a law over the line might be the performative retelling of the story of the victim chosen to be the law’s public face (Megan’s Law, the template for America’s ubiqituous, although ineffective, sex offender registration laws, is a good example of this). It was much the same in the case of FOSTA/SESTA too, for which it was a movie about sex trafficking, along with a series of increasingly fever-pitched (if largely fictitious) stories about the commercial child sex trafficking industry, that made the law unassailable against evidence of its flaws. In the end, all but two Senators voted for a law that has actually made the fight against sex trafficking harder, while also harming sex educators, putting adult sex workers in physical danger, and seeing a rash of privatized censorship sweeping the Internet. Even aside from these laws’ harmful side-effects, they aren’t even fit for purpose, because the vast majority of sexual offending isn’t a result of child sex trafficking, nor is it committed by those who are already registered sex offenders. In fact, notwithstanding popular belief to the contrary, most child sex offending isn’t even committed by pedophiles. That’s not to say that prevention interventions can’t be aimed at these groups, but if that’s where we stop then we are barely scratching the surface of the problem. Politicians and the public alike rely a lot on the stereotype of the child sexual abuser as a creepy old man hanging around a schoolyard in a van, or the brazen sidewalk pimp with links to organized crime. Just as the stereotype of the psycho serial killer represents the much larger problem of violence in America, it can be perversely comforting to be able to focus our attention on these sorts of outlying abusers, as it helps us feel that we have a handle on the problem.

In fact, notwithstanding popular belief to the contrary, most child sex offending isn’t even committed by pedophiles. That’s not to say that prevention interventions can’t be aimed at these groups, but if that’s where we stop then we are barely scratching the surface of the problem. Politicians and the public alike rely a lot on the stereotype of the child sexual abuser as a creepy old man hanging around a schoolyard in a van, or the brazen sidewalk pimp with links to organized crime. Just as the stereotype of the psycho serial killer represents the much larger problem of violence in America, it can be perversely comforting to be able to focus our attention on these sorts of outlying abusers, as it helps us feel that we have a handle on the problem.

What was scariest about Invasion of the Body Snatchers wasn’t the fear an alien might come and kill you or a loved one. The most terrifying part of the movie (spoiler alert!) was the revelation that your loved one was already an alien, and you didn’t even know it. The “red scare” was so scary not because of the reds over the ocean, but because of the reds under the bed. So too, potential child abusers are in every neighborhood, and in many families; they don’t identify (nor would be clinically diagnosed) as pedophiles, and they certainly aren’t going to be prevented from offending by laws aimed at the sex industry or at those who have offended in the past. It’s a sobering thought. But the good news is that the scale of the problem doesn’t have to make us feel paralyzed into inaction. There are things that we can do—it’s just that politicians aren’t going to do them, or at least not for as long as self-righteous morals campaigners and “tough on crime” ideologues control the child protection agenda. What’s needed is a broader primary sex-positive prevention approach that respects the civil and human rights of all. Prostasia Foundation is the first child protection organization to simultaneously champion such an approach, while also criticizing laws and policies that while putatively for child protection, are really nothing more than child protection theater. Formed following the passage of FOSTA/SESTA by a diverse group including child sexual abuse survivors, civil rights campaigners, medical health professionals, and sex industry experts, we are currently crowdfunding with the aim of a full launch next month, and we could use your support.