My great uncle Henry always had a gimmick. One year he was into reflexology and the next time I saw him he was peddling a wonder drug. And when I was fifteen of so, great uncle Henry died. And it wasn’t long thereafter that my great aunt Mildred and her daughter Jean were journeying westward for a family gathering.

“Me and Jeannie were driving across Saskatchewan,” Mildred told us minutes after her arrival, “and it was getting kind of late in the day. I look up at the sky and I see this star and it was really, really bright and it seemed to be moving, as if it was showing us the way to go. And I says, ‘Jeannie, that star is Henry’. So, after a while, the star is hanging in the sky right over this motel by the side of the road, and I says, ‘Jeannie, Henry wants us to stay here tonight.’”

“Was it a nice motel” I asked.

“No,” great aunt Mildred replied, “in fact, it was a real flea bag!”

No one chooses to stay in a fleabag motel; but sometimes there you are.

There are worse things, of course, than a fleabag motel. A stable, for instance.

We imagine Christmas as a celebration of comfort and contentment. The first Christmas didn’t fit the bill.

There was no heat.

There was no light.

There were domestic animals like cows and donkeys and the stench was overpowering.

And then Mary’s water broke.

Like any young mother-to-be, Mary had fantasized about giving birth in a nice, warm, clean room, surrounded by her mother and her sisters and the village mid-wife.

Mary was grieving the loss of her dream when the shepherds arrived. All Mary and Joseph had was their privacy and then they didn’t even have that.

The first Christmas begins with grief and ends in glory.

Grief and glory seem like polar opposites, but in the Bible they are always found together.

We have grief without glory all the time, of course. But glory always walks with grief. Always.

Grief is a foreign country. When you have lost someone you love, someone stationed firmly at the center of your personal universe, everything looks strange. It’s like driving past a familiar scene in a dense fog.

As the Doors put it four decades ago, “People are strange when you’re a stranger, faces look ugly when you’re alone.”

Have you ever wondered why the angel choir didn’t sing for Mary, Joseph and the babe? The holy family got the message second-hand. Only a pack of random shepherds caught the show.

When God told the angels to appear to certain poor shepherds, did they push back?

“Tonight the king of kings is to be born and you are to make the announcement,” God tells his angel in chief.

“Where are we going,” the head angel asks, “Rome? Jerusalem?”

“I’ve got no friends in Caesar’s Rome,” God replies slowly, “and I’ve got no friends in Herod’s Jerusalem. In fact, it appears I’ve got no friends in the little town of Bethlehem. But I’ve got friends in low places and I want you to give them a lift.”

“Shepherds?” Gabriel asks. “Really?”

“Yes, shepherds.” God says, “You don’t like Shepherds?”

“You realize,” the angel counters, “that these guys have been abiding in the fields, keeping watch over their flocks by night, after night, after night. Do you know how long it’s been since they’ve had a decent bath?”

“Forty-six days, four hours, forty-six minutes, twelve seconds and counting” God answers.

“Oops!” the head angel says. “Shepherds it is!”

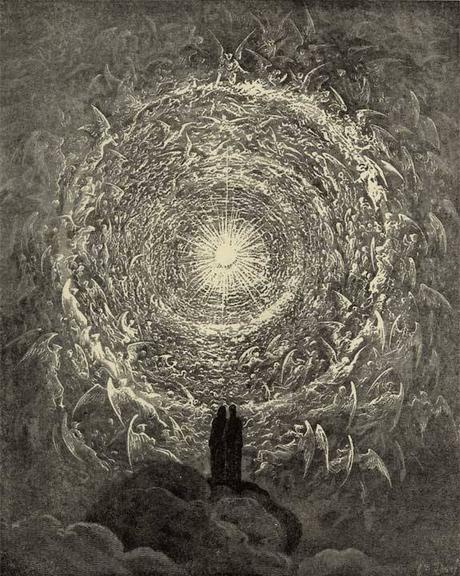

And, lo, the angel of the Lord came upon them,

and the glory of the Lord shone round about them:

and they were sore afraid.

The shepherds were scared witless by the glory of God.

The glory of the Lord is the sense, or premonition, that Almighty God has big plans, and that those plans pertain to you personally. That’s a very scary notion.

When we are mired in grief, we typically lower expectations. It is likely that nothing good will happen in my world ever again, we say, and I can deal with that. Shepherds coped with the shame and grime of their job by keeping their expectations in check.

And then the glory of the Lord is shining round. Angels don’t just appear for our personal entertainment; they always have an agenda.

“Fear not,” the angel cried,

For behold, I bring you good tidings of a great joy that shall be to all people;

For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Savior which is Christ the Lord.

“What has the birth of Messiah got to do with us”, the shepherds must have wondered. “We’re shepherds, for God’s sake.”

Then comes the punchline:

Ye shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes

and lying in a manger.

What is a manger? That’s right, a manger is a feed trough for domestic animals.

A baby born in a barn and lying in a feed trough is the kind of Messiah shepherds can relate to.

And suddenly there was with the angel the multitude of the heavenly host

praising God and saying,

‘Glory to God in the highest

and on earth, peace, good will toward men’.

Mary and Joseph were too busy trying to keep their manger baby warm and comforted to hear the approach of unexpected guests.

“There he is,” one shepherd hollered; “the manger messiah, just like the angel said.”

And then all the shepherds were talking over one another. But it wasn’t long before their strange and wonderful tale tumbled out.

Mary never got to see the host of heaven who hailed Messiah’s birth, but she believed the story anyway. And for the rest of her life she would ponder this strange night in her heart.

We don’t get the story first-hand either. But we grab the good tidings and hold on for dear life.

Grief mingled with glory. That’s Christmas. You don’t have to believe me, but I ask that you think about it. That you ponder it in your heart.

In 1849, a preacher named Edmund Sears wrote the old carol “It Came upon the Midnight Clear”. Sears was sunk so deep in depression that, for a time, he couldn’t function as a full-time pastor. Political violence was breaking out all over Europe that year and the Mexican-American war, which he staunchly opposed, had just ended in a glorious victory that put America on the path to empire. Sears had dedicated his life to ending slavery, but the United States was staggering toward a Civil War too horrible to contemplate.

Yet, because of Christmas, the world’s grief was shot through with glory.

The final verse of Edmund Sear’s Christmas carol could never have been written by the comfortable and the contented and that’s why it has brought hope to millions of people over the past 168 years, including me, and, I hope, you:

And ye, beneath life’s crushing load,

Whose forms are bending low,

Who toil along the climbing way

With painful steps and slow,

Look now! For glad and golden hours

come swiftly on the wing.

O rest beside the weary road,

And hear the angels sing!