Reductionism is beguiling because of the exalted status it gives to the human intellect. It is presumed that rational thought can explain everything. Still, reason sometimes leads to paradoxes—we’ve all heard the (admittedly theistic) one asking if God can create a rock so heavy s/he can’t lift it. Given the premise, two strands of logic conflict. A similar sort of phenomenon, it appears, accompanies quantum physics. In a story from last year on Big Questions Online (a website supported by the Templeton Foundation), Stephen M. Barr submitted a piece entitled “Does Quantum Physics Make it Easier to Believe in God?” The article requires some concentration, but the basic premise is simple enough to explain: quantum physics does not sit well with reductionism. There seems to be will in nature. It may not be God in the machine; it may not even be a machine at all.

I have always been fascinated by science, and I am not one to castigate it. Its string of successes stretches all the way from atoms and their explosive tendencies to the moon and Mars and beyond. At the same time, most of us have experienced something that “should work,” in which no fault can be discovered. Reductionism would declare the fault is indeed there, just undetected. If, however, at the sub-atomic level, particles sometimes act uncannily, don’t those effects climb the ladder into the visible world in some way? Logic would seem to demand it. The problem with putting will into the equation is that will can’t be quantified. There have been many documented cases of an instance of superhuman strength coursing through a person when they have to rescue a loved one. We raise our eyebrows, mumble about adrenaline and pretend that will hasn’t affected nature in this reductionistic, strictly material world.

Denigrating human brain power is not something I undertake lightly. Logic works most of the time. A thinking creature who has evolved to be a thinking creature, however, must realize that its own intellect is limited. Simply because we are limited doesn‘t mean we shouldn’t strive to improve, but it does mean that ex cathedra statements, whether from pontiffs or physicists, should be suspect. One would be hard-pressed to label Einstein a believer. Yet even he made the occasional remark that left the door open for, well, maybe not God, but maybe not reductionism either. I was once told, and I believe it to be true, that you can tell a truly educated person not by how much he or she claims to know, but rather by how much she or he claims not to know. It may not seem logical, but down there among the particles of the quantum world, I suspect those willful quarks agree.

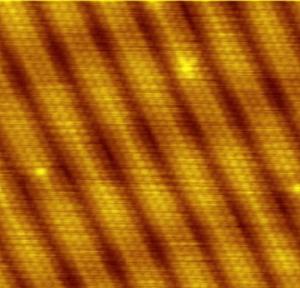

Erwinrossen’s image of atoms, the sight eyes can’t see