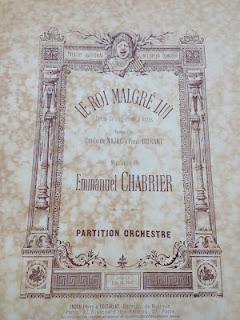

Le Roi Malgré Lui, Emmanuel Chabrier's 1887 opera, is a curious work; admired for its creative orchestration by Ravel, Stravinsky, and others, it has nonetheless remained infrequently performed. Its somewhat convoluted comic plot is very loosely based on the sixteenth-century election of Henri de Valois as King of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In Chabrier's hands, this becomes a whimsical tale of a young man who would definitely not like to be king, preferring the life (and loves) of a soldier-prince. To this end he joins the elite conspiracy against himself, which is led by his bitter ex-lover Alexina, who is married to his chamberlain. To a doggerel libretto which Chabrier himself wryly likened to a stew, disguises, romantic duets, and mistaken identities ensue, creating a degree of confusion exceptional even for comic opera. All ends with a rousing chorus, of course (it is indicative of the opera's tone that dire warnings are interrupted by lovers' vows, and the actual plotting is overshadowed by a waltz.) The French and the Poles indulge in gleeful mutual stereotyping, with jokes at the expense of each and music to match, e.g. the Fête polonaise. There's even a romance between the king's best friend (Nangis, the tenor) and a local girl (Minka, who sings gypsy songs about love.) On paper, it's all rather charming; in practice it is considerably more than that.

Le Roi Malgré Lui, Emmanuel Chabrier's 1887 opera, is a curious work; admired for its creative orchestration by Ravel, Stravinsky, and others, it has nonetheless remained infrequently performed. Its somewhat convoluted comic plot is very loosely based on the sixteenth-century election of Henri de Valois as King of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In Chabrier's hands, this becomes a whimsical tale of a young man who would definitely not like to be king, preferring the life (and loves) of a soldier-prince. To this end he joins the elite conspiracy against himself, which is led by his bitter ex-lover Alexina, who is married to his chamberlain. To a doggerel libretto which Chabrier himself wryly likened to a stew, disguises, romantic duets, and mistaken identities ensue, creating a degree of confusion exceptional even for comic opera. All ends with a rousing chorus, of course (it is indicative of the opera's tone that dire warnings are interrupted by lovers' vows, and the actual plotting is overshadowed by a waltz.) The French and the Poles indulge in gleeful mutual stereotyping, with jokes at the expense of each and music to match, e.g. the Fête polonaise. There's even a romance between the king's best friend (Nangis, the tenor) and a local girl (Minka, who sings gypsy songs about love.) On paper, it's all rather charming; in practice it is considerably more than that.

The score really is lovely, always ready to undercut its own conventions with unexpectedly poignant harmonies or sly instrumentation, combining romance and satire to good dramatic effect, with fine individual characterization; I appreciated many of its nuances more when seeing the staging rather than just listening. The American Symphony Orchestra, under Leon Botstein, contributed lively playing, and brought off both fanfares and nocturnes nicely. Moreover, the production created for Bard SummerScape by Thaddeus Strassberger is smart, sleek, and sexy, combining historical and musical intelligence. Chabrier's score hints that the grand patriotic choruses and solemn vows are perhaps not to be taken too seriously, and states outright that indulging in romantic idealization is almost certain to lead to trouble. Strassberger brings us, via a credits sequence over the overture that could have been modeled on that of The Prisoner of Zenda, to a Hollywood soundstage of the era of Lubitsch and Selznick. Here the chorus is divided between dilettantes at a Casablanca-era roulette table and card-playing dilettantes powdered and bewigged in the manner of Europe's anciens régimes. Spectator to all of this is a Chabrier lookalike who turns out to be Basile, an obsequious innkeeper introduced in the third act. He sits in a dingy room, unfurnished save for his armchair, his television set... and a large, framed photograph of John Paul II, a clever allusion to Henri de Valois' participation in the French Wars of Religion (and the religion which was not the least of his qualifications as king-elect of Poland,) which is also used to bitterly satirize hypocritical and unavailing piety later on. To enumerate all such elements would be unavailing, if not actually impossible; the production is very busy. To a fault? Possibly; but the 'background' is usually accomplishing something as well as doing something, if only to call attention to a diversity of sexual and religious identities often obscured on the stages of Belle Epoque Paris and 1930s Hollywood (not to mention our own) if not in their audiences. Bourgeois aspiration dependent on elitism, consumerism, the sort of misogyny that cloaks itself in a patronizingly indulgent manner... there's not much that doesn't come in for satire. This reading of the libretto is so effective that it's hard to imagine Chabrier didn't at least see its possibilities. Believe it or not, it is a comedy: the waltz is given a dance routine recalling Astaire, and Minka's torch songs are staged with an extravagance that would have delighted Sam Goldwyn. As the disrupted staging of the final tableau makes clear, life's emotional and political entanglements can rarely be resolved with a rousing chorus.

Crucial to the success of the evening was the fine work of the singers, individually and as an ensemble. This extends to the role of Basile; his oft-repeated signature line was given with varied expression to hilarious effect by Jason Ferrante, who also handled the silent part of the role well. As the Polish count Laski, Jeffrey Mattsey's sound was a bit blustery but given his coarse persona, this worked, and he played the villain with gusto worthy of Raymond Massey. Bass Frédéric Goncalves gave the buffo role of Fritelli with wit that was never unduly heavy, fine phrasing and diction, warm tone, and idiomatic Italian to boot. Nathalie Paulin made a richly sensual Alexina, with a full, gleaming soprano and a glamorous stage presence. Flirtatious and determined, she had good vocal and dramatic chemistry with Liam Bonner's Henri. As Minka, Andriana Chuchman was consistently engaging; she handled the vocal demands of the role with considerable flair. Chuchman's soprano has a pleasing chiaroscuro timbre, and she wielded it with expressive agility. For the rest, she played the secret agent/femme fatale brilliantly, possibly channeling Barbara Stanwyck. Michele Angelini sang the role of her lover, the somewhat feckless Nangis, with impressively consistent beauty of phrasing and tone. Liam Bonner brought a mellifluous baritone, very good French, and William Holden levels of charm to the title role. As Henri, he always seemed ready enough to laugh at himself that his self-pity and self-indulgence were readily forgiven, and his aplomb seemed nothing damaged by having to perform in various states of undress. Whether lamenting the sunshine of France, flirting and conspiring with Minka, conspiring and flirting with Alexina, or taking vows to take (or preserve) his own life, he sang expressively and engagingly. Acknowledging both the frivolity and the intelligence of Chabrier's score, the whole thing was tremendous fun.