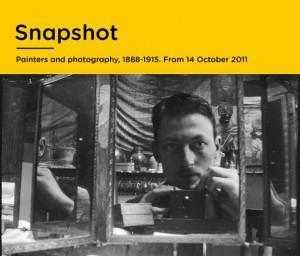

The Kodak camera isn’t viewed the way it used to be. In an age of instant gratification photography where every mobile phone is a camera and developing takes just seconds, a “Kodak moment” is a thing of the past. But at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum, the mystery and magic of photography is reborn in the new exhibit ‘Snapshot.’

From 14 October until 8 January 2012, the museum hosts seven painters from the Netherlands, Belgium and France working during the turn of the 20th century. Their legendary works of art are held against the backdrop of the artist’s latest tool – the camera.

Each of the artists, including Henri Evenepoel, Edouard Vuillard and George Hendrik Breitner, used the new medium to capture everyday moments with family and friends. But each of these images also held a place in their art.

Whether the camera was used for inspiration, to set up the perfect painting, or as a foray into graphic design, these artists collected hundreds of snapshots. Only in this exhibition can each artists view of their photographs be used to discover more about their craft.

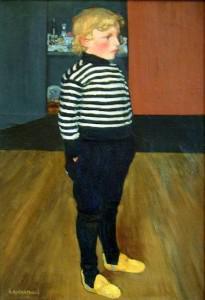

Evenepol, for example, took numerous pictures of his nine children and wife with his camera, filling album upon album. But the images are also a central theme to his painting, with his children as subjects in scenes very similar to the photographic images.

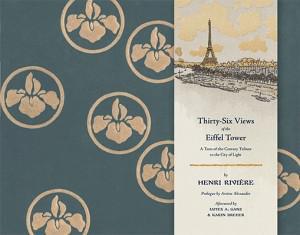

In a more daring atempt, Henri Riviere photos the nearly completed Eiffel Tower, becoming one of the first to exhibit such graphic imagery through a camera lens.

Nearly all of the 200 photos exhibited at the Van Gogh Museum are original negatives. Some, it was revealed, come from the very attics and albums of the painters’ living family members.

‘Snapshot’ is a unique offering at the Van Gogh, bringing camera-ready imagery to the hailed world of painting. But here, the two concepts bring a surprising insight into the use of the camera in creating depth, composition and new perspectives to the world of art as a whole. And at the simple joys and pleasures that photography once provided, before it became a habit of the “mainstream.”