A person of many astute observations, one of Robert Bellah’s most astute is his refrain (when talking about the history of religions) that “nothing is ever lost.” By this I take Bellah to mean that at any given point in time, an existing religion will contain elements from earlier religions. There is continuity in religious history and “new” religions are never sui generis. Because these elements have been transformed and are continuously being reconstituted, identifying them can be a challenge. The first step in any such identification is knowing what came before.

One of the world’s oldest supernatural practices, aspects of which can be found in all of today’s “world religions,” is divination sensu lato. It is no accident that the earliest organized religions, those which arose in conjunction with Neolithic city-states, revolved around divination. And as some city-states grew into empires, divination remained front and center. In China emperors interpreted the tortoise shells and oracle bones, while in Rome they consulted sacrificial livers and conferred with augurs or auspices. When things did not augur well or omens were inauspicious, plans were changed or put on hold. Around the world, the affairs of city, state, and empire were conducted in accordance with divination.

Attempts to ascertain (and by extension control) the future did not originate in classical antiquity. Noting that hunter-gatherers around the world divine the location of game or enemies by “reading” viscera and bones, anthropologists have surmised that the practice is more ancient. Because such inferences rely on ethnographic analogy and backward projection, what was a reasonable surmise long remained uncertain. The discovery of 14,000 year old “dice” and a divining scapula at El Juyo Cave in Spain make it almost certain.

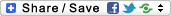

Few Paleolithic archaeological sites are richer than El Juyo Cave. Used extensively by Magdalenian hunter-gatherers 14,000 years ago, it contains what may be the world’s oldest ritual sanctuary, highlighted by a large carved rock face or “spirit” at the entrance.

In “Coping with Chance: Animal Bones and the Aleatory,” Freeman and Echegaray (2005) report on two extraordinary finds from El Juyo. The first is a set of three worked bone pieces, similar in size and shape, which were found stacked on top of one another and which probably were bound together as a set. They greatly resemble “dice” sets used by Amerindians and the authors interpret them as such. The second is a deer scapula or shoulder blade that has been engraved with images of deer, incised, drilled, burned, and shattered. Because this kind of treatment precisely parallels divination practices among known hunter-gatherers, the authors’ scapulimancy interpretation is uncontroversial.

What I like most about the authors’ report is their extended meditation on the relationship between divination and chance:

In the specific cases to be discussed here, bone artifacts seem to reflect game-playing and/or divination, and to attest to early attempts by Upper Paleolithic humans to deal with chance: to cope with the seemingly “uncontrollable” randomness of natural phenomena. [Humans] find it hard to understand that many natural phenomena are simply random, a fact that is at least perplexing if not troubling, and that leads us to invent various means of coping with this randomness.

It is a characteristic of [humans] to behave as though such random phenomena as the availability of game, the likeliness of success in the food quest, and other vagaries of nature could be controlled or, what is the same thing, “divined” or predicted, in the sense of determining their indeterminable future direction.

[W]e can show that there are artifacts such as “dice” and engraved scapulae in the bone inventory from the Magdalenian site of el Juyo (presumably other such pieces have been or will be found in other Upper Paleolithic sites as well) that are most effectively explained as devices showing an awareness of the effects of chance and as implements to predict the direction of the aleatory: to cope with the randomness of nature.

While some may wish to dismiss ancient divination practices as mere “magic” or superstition, we would do well to remember that nothing is ever lost. It is but a short conceptual step from Paleolithic divination to the kinds of prophecy that are so characteristic of Axial or modern religions. If we are going to draw lines, they should not be conceptual lines of sand but rather historical lines of continuity.

Reference:

Freeman, L.G., & Echegaray, J.G. (2005). Coping with Chance: Animal Bones and the Aleatory Munibe (Antropologia-Arkeologia), 57, 159-176