From Ferguson to Freedom, Part 2: Institutional Racism in America

By: Andrew Gavin Marshall

16 December 2014

Part 1: Race, Repression and Resistance in America

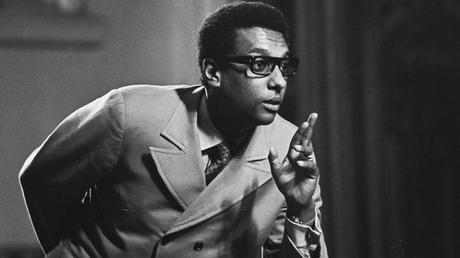

Stokely Carmichael

The primary issue of race in America, as elsewhere in the world, is less about the overt acceptance and propagation of racism on the individual level, and more about the realities of institutional racism. A racist society is established and sustained not simply by racist individuals, but by racist institutions and ideologies. If racism were simply an individual experience, education and interaction between racial groups would seemingly be enough to eradicate the scourge of racism in modern society. After all, most white Americans would likely not identify as racists, and in a society where a black man can become president, many may be tempted to proclaim that America is a “post-racial society.”

Viewing racism simply from an individual level is misleading, embracing the notion that because I am not a racist, we no longer live in a racist society; because the president is black, we have moved beyond racism; because there are black people who have succeeded in society and risen to top political and economic positions of power, there are no longer issues of racial segregation and oppression. These views present a mythology of ‘equal opportunity’ and ‘individual initiative.’ In other words, segregation and other overt forms of political and legal racism have been largely dismantled, and therefore, the rates of poverty, crime, imprisonment and death in black communities are no longer the result of a racist society, but rather, a lack of “individual responsibility” and failure to take advantage of the equal opportunities afforded.

Institutional racism, however, takes a view of society, of the relations between power and people, beyond the myopic and misleading focus of ‘the individual’ alone. Society is institutionally structured to support the rich and powerful at the expense of the vast majority of the population, which is evident through the structures, policies, and effects of institutions like the Treasury Department, Federal Reserve, Wall Street banks, the IMF, World Bank, World Trade Organization, etc. The ideologies and actions of these institutions effectively protect the powerful, bail them out, promote policies which benefit them, punish the poor, impoverish the rest, and support a top-down power structure of the national (and global) economy.

There may be individual policymakers, executives or economists who advocate more economic equality, who criticize bailouts and austerity, who oppose the parasitic nature of the modern economy. However, when sitting in positions of power and influence, these individuals must succumb to the institutional demands of those positions. An executive at a bank may individually oppose the actions of banks in creating financial crises and then needing bailouts and profiting from them as millions lose homes, go hungry and are pushed into poverty. However, that executive cannot change the operations of the bank or realities of the industry alone, he must be concerned with the institutional realities, which focus on short-term quarterly profits for shareholders, which in turn would require him to follow and mimic the actions and initiatives of all the other big banks. If such an executive did not follow the path as designed by the institutional structure of the bank and financial markets, such an executive would be fired. Institutional inequality and economic exploitation are realities of the economic system, regardless of whether or not there are individuals within the system who oppose many of the policies and effects of that system.

The same logic applies to racism. This has been true for as long as racism has been a reality. In the United States, racism was institutionalized from the beginning, as the U.S. was founded as a Slave State. Racism was a legal reality, and it was reflected in the institutional structure of the economy, labor system, education, health care, politics, geography, demography, the criminal justice system, city planning, foreign policy and empire. Over the course of decades and centuries, there have been many tangible improvements, with reform to various institutions, legal changes and social transformations: the end of formal slavery, Civil Rights Movement, voting registration, etc. Yet, despite these various improvements and changes over the course of centuries, the realities of institutional racism remain in many facets, old and new. Institutional racism is embedded in the original and evolving structure of society as a whole, and to effectively challenge and remove racism from society, most of society’s dominant institutions must also be challenged, changed or made obsolete.

The institutional structure of society largely serves the same purpose, to protect and support the rich and powerful as the expense of the vast majority of the population. This is true, regardless of race. However, those same institutions enforce segregation, exploitation, domination and exclusion not only in terms of class, but also race. This has the effect of dividing the population among themselves, pitting white against black, promoting and maintaining social divides and conflicts between the population to ensure that they do not unite (through experience or action) against the true ruling groups and structures of society. Racism thus allows for more effective control of society by the few who rule it.

Stokely Carmichael helped to popularize the term ‘Black Power’ in the late 1960s, having risen to acclaim as a young leader in the Civil Rights movement. In 1966, Carmichael published an essay in The Massachusetts Review entitled, ‘Toward Black Liberation,’ in which he wrote that, “The history of every institution of this society indicates that a major concern in the ordering and structuring of the society has been the maintaining of the Negro community in its condition of dependence and oppression… that racist assumptions of white superiority have been so deeply ingrained in the structure of the society that it infuses its entire functioning, and is so much a part of the national subconscious that it is taken for granted and is frequently not even recognized.”

Carmichael provides an example to differentiate between individual and institutional racism: “When unidentified white terrorists bomb a Negro Church and kill five children, that is an act of individual racism, widely deplored by most segments of the society. But when in that same city, Birmingham, Alabama, not five but 500 Negro babies die each year because of a lack of proper food, shelter and medical facilities, and thousands more are destroyed and maimed physically, emotionally and intellectually because of conditions of poverty and deprivation in the ghetto, that is a function of institutionalized racism. But the society either pretends it doesn’t know of this situation, or is incapable of doing anything meaningful about it.”

Carmichael described the ‘Negro community in America’ as being subjected to the realities of “white imperialism and colonial exploitation.” With more than 20 million black Americans accounting for roughly 10% of the national population (in 1966), they lived primarily in poor areas of the South, shanty-towns, and the urban slums and ghettos of northern and westerns industrial cities. Regardless of location in the country, if one were to go into any of these black communities, Carmichael wrote, “one will find that the same combination of political, economic, and social forces are at work. The people in the Negro community do not control the resources of that community, its political decisions, its law enforcement, its housing standards; and even the physical ownership of the land, houses, and stores lie outside that community.” Instead, white power “makes the laws, and it is violent white power in the form of armed white cops that enforces those laws with guns and nightsticks. The vast majority of Negroes in this country live in these captive communities and must endure these conditions of oppression because, and only because, they are black and powerless.”

The realities of institutional racism can be seen in the case of Ferguson. An analysis by Keith Boag of CBC News looked at the legal structure of St. Louis County, where two-thirds of the population, approximately 650,000 people, live within “incorporated municipalities.” There are roughly 90 of these municipalities, Ferguson being one such area, with a population of roughly 21,000 people. Fourteen of these areas have populations less than 500 people, and 58 of them have their own police forces. Boag describes the origins of this structure as dating back several decades to before the Civil Rights movement, when white people in the city of St. Louis fled to the suburbs as poor blacks moved to the inner city. As whites moved out of the city, they sought more autonomy and local power, establishing the system of ‘incorporated municipalities’, allowing the local populace to control their own development, writing legal ‘covenants’ which imposed restrictions on “who could buy or lease property within its boundaries.”

In 1970, Ferguson was 99% white, with their covenant enshrining in law that blacks could not sell, rent own property in any way. Over the decades, the covenants were eroded due to their overt racist forms, and they became “unenforceable.” Thus, black people from the city were able to move out to the suburbs, but had to inherit the plethora of jurisdictions left behind by the white population who continued to flee the movement of the black population. In many of these small jurisdictions, there are too few people to provide for a necessary tax base to afford the services and functions of the local administrative structure. The result was that many communities became increasingly dependent upon “aggressive policing” to raise revenue through ticketing and traffic fines.

Boag describes this as a “tax on the poor,” since they are the most susceptible to such practices: “It’s they who have trouble finding the money to pay fines. It’s they who may have to choose between driving illegally to work or not working. It’s they who may be struggling just to feed a family.” The main preoccupation of police becomes issuing traffic fines and tickets, and then arresting people for not paying those fines. As a result, people do not view the police as being there to ‘protect and serve’, but, rather, “to pinch and squeeze every nickel out of you in any way they can.” This system is rampant in the town of Ferguson, as confirmed in an investigation by the Washington Post.

In effect, the poor black population of Ferguson is thus made to pay for their own oppression, stuck in a cycle of poverty which forces them to pay fines (or go to prison) in order to pay the salaries of the police who fine them, arrest them, beat them and kill them.

Thus, racism in Ferguson, itself a product of the segregationist policies of the Jim Crow era, is institutionalized in the very legal structure, tax and revenue structures, city planning and law enforcement institutions. Such circumstances do not require an overt articulation of racism, nor for it to be enforced by individual white racists (though both of these realities also occur and are encouraged by such a system).

The same logic also applies to the official system of slavery that existed in the United States prior to the Civil War. The slave system was an inherently and obviously racist system. However, there were (on occasion) slave owners who would treat their “property” with kindness, even those who criticized and opposed the system of slavery, but would still participate within that system. The realities of the institutional system of slavery meant that despite an individual’s personal views and preferences, they operated within a system which was racially structured, and thus, were made active participants and supporters of a racist system of domination and exploitation.

If one white slave owner were to free his slaves and promote equality and justice, he would lose his entire economic, social and political base of power within the society, be ostracized and made irrelevant and ineffective. Further, the newly-freed slaves would likely be captured and sold to other slave owners, with ‘freedom’ a short-lived and largely symbolic experience. The actions of a moral individual within an immoral institutional structure cannot change anything alone.

What is required is the collective action of many thousands and hundreds of thousands of individuals, working together to make the costs of such a system greater than its perceived benefits, forcing institutional change. Collective and large-scale actions will, in time and struggle, force reform and gradual change from the top-down. Alternatively, collective action and radical struggle will add to this same pressure, but also propose, organize and initiate alternative methods and visions for social organization and objectives, promoting more revolutionary alternatives.

The events and reactions in Ferguson, New York and increasingly across much of the country and even internationally represent the emergence of a powerful new and resurgent force in society, the reactivation of people power. From urban rebellions and ‘riots’ in Ferguson and Berkeley, to mass arrests and protests in New York and Los Angeles, to the civil disobedience in Miami, Boston, Chicago, Seattle and beyond, America is witnessing the first few weeks and months of a powerful new social movement which promises not to go away quietly. Nor should it.

With chants of “shut it down!” the demonstrators recognize that their power comes in the form of being able to disrupt the normal functioning of society. Institutional racism has led to immense injustice, segregation, exploitation and domination over life in America. The realities of present-day America are the modern manifestations of an institutional system of racism which pre-dates the formation of the United States itself. The current unrest is a reflection of the fact that solutions must go to the core of the problem, within the founding and functions of the institutions themselves.

America may have a black president, but he still has to live in the White House. Black Americans may have more political freedoms and opportunities than in previous decades and centuries, but they still have to live in a society shaped and dominated by institutional racism.

The black population has been kept at the bottom of the social order in the United States since the U.S. was founded as a country (and in fact, long before then). This has been unchanged over the course of several centuries. If progress is defined as one black man being able to rise to a position over which he exerts immense power over a society that continues to subject the majority black population to institutional racism, then ‘progress’ needs to be redefined. An individual, alone, cannot alter the institutional structure of society. Obama is not a symbol of a “post-racial” America, he is a symbol of the continued existence of an “institutionally racist” America, where one can have a black president overseeing a white empire, at home and abroad.

Obama is the exception, not the rule. The rule is Ferguson; the rule is Michael Brown and Eric Garner. The rules need to change. The rules need to be broken and replaced. The rule of racist and imperialist institutions and ideologies must be smashed and made obsolete. The rule of the people must become the law of the land. The road to justice runs through Ferguson, driven by the collective action of thousands of individuals, taking the struggle into the streets with the very real threat that if true liberation is not achieved, the system has lost any sense of legitimacy. When the cost of subservience to the status quo is greater than the cost of changing it, the people will “Shut It Down.”

Andrew Gavin Marshall is a freelance researcher and writer based in Montreal, Canada.