By Alan Bean

By Alan Bean

Just over three years after Curtis Flowers was convicted for murdering four people at a Mississippi furniture store in 1996, his attorneys have filed an appeal. You may wonder how it could take three years to compose an appeal brief, especially in a case so open-and-shut that a jury took only 29 minutes to render a guilty verdict.

This wasn’t Curtis Flowers’ first courtroom rodeo. In fact, he has gone to trial on these charges six times, more than any other capital defendant in the history of American jurisprudence.

Convictions in Flowers 1 and 2 were reversed by the Mississippi Supreme Court due to gross prosecutorial misconduct (primarily arguing facts not in evidence) and racially biased jury selection procedures. Other trials ended in hung juries, largely because DA Doug Evans, fearful of another reversal, didn’t take heroic measures to keep African Americans off the jury. In the most dramatic case, five Black jurors voted to acquit while seven White jurors found Evans’ case convincing.

I have been working to attract major media attention to this case since 2007. Apart from a British Broadcasting Corporation story, and some good trial coverage by CNN in 2010 (here and here) I have come up empty. The case received a lot of blog attention during the most recent trial, but (as is often the case) attention flagged post-verdict.

Recently, Paul Alexander, a veteran journalist with a number of well-received books and a host of high-profile magazine articles to his credit, released an eBook on the Flowers case and followed up with a Daily Beast article. Alexander still wants to write a full-length book on the Flowers story but thus far has been unable to get a publisher to bite even though he has an established reputation.

Like me, Alexander has concluded that Flowers couldn’t possibly have been the trigger man in 1996. There is no meaningful physical evidence linking him to the crime. The witnesses the state has used to tie him to the crime scene are almost comically lacking in credibility and contradict one another at every turn. Flowers had no motive for wanting any of the victims dead, he had no way of procuring the murder weapon, he lacked the expertise and experience to dispatch four victims execution-style without resistance, he didn’t even have a car to drive to and from the scene.

If the case is that weak, why were White jurors in Winona, Mississippi so convinced by the state’s case that, after dealing with administrative matters, they arrived at a verdict in a matter of seconds?

That’s the key problem here. If Curtis Flowers is an innocent man, parts of Mississippi haven’t moved far beyond the undisguised racism of an earlier period. To examine this case closely and critically is to conclude that prosecutor Doug Evans decided to pin a horrific murder on the most likely Black suspect he could find, and shaped the evidence to fit a conclusion he reached on a hunch.

That is precisely what happened, but no one wants to admit it. Accusing small town Mississippi officials of racism is so 1963. We’ve been there and done that. We desperately want to believe those days are gone for good.

And in a sense they are. Thus far the Supreme Court of Mississippi has slapped Doug Evans hand every time he broke the rules in the to convict Mr. Flowers. The state’s highest court has repeatedly sanctioned Evans for racial bias.

The Flowers case reveals two Mississippi’s at war with one another. Unfortunately, every time the Supreme Court accuses Evans of breaking the rules, the only remedy is to let him give it another go–as if the racial bias in this case has been unintentional or inadvertent.

Part of the reason this appeal brief has taken three years to complete is that the old Mississippi (represented by Doug Evans and his associates in Grenada) have refused to hand over critically important information to the Flowers team.

A final reason for the delay is that defense counsel worked hard and long for permission to present what might be the most damning indictment of Evans to emerge in the course of this ancient saga. Unfortunately, their valiant efforts came to naught.

As a result, the justices of the Mississippi Supreme Court will not learn that Patricia Hallmon/Odom/Sullivan, the woman the state’s timeline is built around, recently served time in federal prison for tax fraud. Doug Evans knew his star witness was under federal indictment at the time of Flowers’ 2010 trial (his former assistant was defending her and the two men were in frequent contact) and failed to notify defense counsel. For legal reasons beyond my pay grade, Evans dodged a bullet and the embarrassing facts concerning his star witness were ruled out of bounds.

In a major departure, the Office of Capital Defense in Jackson, Mississippi reached out to the Death Penalty Project at Cornell University’s Law School for assistance. This turned out to be an excellent decision. Cases like this demand fresh eyes and the best legal counsel in America. The involvement of world-class attorneys made all the difference in Tulia and Jena, and the Flowers case is no exception. It appears that Sheri Lynn Johnson, the James and Mark Flanagan Professor of Law at Cornell, did the heavy lifting on the Flowers appeal. The writing and the argumentation are lucid and compelling in every particular.

Most significantly, from my perspective, the Flowers appeal incorporated almost all the arguments I have raised in my blogging over the past six years. They may have been influenced by my work, or they may have arrived at similar conclusions because that’s where the evidence leads. I really don’t care. The arguments are now on the record–that’s all that matters.

Let me boil 204 pages of legal argument down to a few highlights

Summary of Flowers appeal

Although Doug Evans has long dismissed my contention that no other capital defendant has been tried six times in the United States, the attorneys responsible for this appeal brief scoured the record and were unable to find another capital case that has been tried more than five times. This is one of the reasons why they argue repeatedly that the verdict should be vacated, Flowers released from solitary confinement in Parchman prison, and the State of Mississippi barred from retrying this case on double jeopardy grounds. At some point, somebody needs to say enough-is-enough. If you couldn’t get a final conviction in six attempts, it’s over.

Amen to that.

There is one major departure from my take on this case, but even here I am impressed. Flowers’ team makes a compelling argument that the state could have made a much more convincing case against Doyle Simpson and his brother Emmit than they made against Curtis Flowers. According to the state’s theory of the crime, Curtis Flowers left his home early in the morning and walked to the parking lot of the Angelica clothing factory where he stole the murder weapon from an unlocked car belonging to Doyle Simpson. Flowers then returned home, changed clothes, walked to the Tardy furniture store, killed four people, and ran home.

This tortuous tale was built around the testimony of Patricia Hallmon, Flowers’ neighbor.

Making Doyle Simpson the prime suspect removes most of the problems that have dogged the state’s case from the outset. There is a general consensus that the murder weapon belonged to Doyle Simpson and no one has ever explained how Flowers knew where to find the gun. If Flowers had been searching cars at random, the defense argues, he would hardly have started with Simpson’s old and filthy-dirty vehicle.

All these problems would have disappeared if the state had directed its suspicions to the actual owner of the gun.

According to trial testimony, Simpson was eliminated as a suspect because coworkers claimed he had been at the Angelica plant on the morning of the murder. Unfortunately, the officer who made these claims didn’t take names or record actual comments, so this allegation is open to question. Trial testimony suggests that Simpson regularly left the plant in his vehicle during work hours and his own sister has repeatedly testified that she saw him driving around on the morning of the murder. Curtis Flowers didn’t own a car, which explains why the state’s theory of the case involves so much walking and running. Point the finger at Doyle Simpson and a much simpler scenario emerges.

Moreover, Porky Collins has testified that he saw two Black men arguing in front of the Tardy furniture store shortly after the crime took place. Collins noted that a remarkably dirty, tan vehicle was parked on the boulevard next to these two men.

That’s a perfect description of Simpson’s car.

There’s more. When police officers went to the Angelica plant to interview Doyle Simpson shortly after the murder, Doyle’s brother was on the premises and ran from the police. In fact, Doyle initially accused his brother of stealing his gun.

When asked where he got the murder weapon, Doyle lied to the police.

No one has ever explained how a man like Curtis Flowers, with no military experience or gang involvement, could calmly execute four victims execution style with no sign of flight or a struggle. There may be people who can control a room like that, but Curtis Flowers is not one of them. As I have repeatedly argued, if you add a second gunman this problem evaporates.

However, because Doyle Simpson was immediately excluded as a suspect, his home was never searched and he was never tested for the presence of gunshot residue.

So, with all these factors working against him, why didn’t the state regard Doyle Simpson as a suspect?

Because it didn’t matter which Black man took the fall and Roxanne Ballard, the daughter of Bertha Tardy, believed Flowers was the culprit. She didn’t know Curtis personally, but she saw a small paycheck in his name on her mother’s desk and, still in shock, made a wild imaginative leap.

Curtis had worked at Tardy’s for three days but quit showing up for work and was eventually replaced.

The state argues that Curtis was angry because Bertha Tardy sacked him for failing to show up for work for a full week. But as the defense argues in the appeal, Bertha Tardy had good cause to be angry with Flowers, not vice versa.

I haven’t singled out Doyle Simpson for suspicion because, like Curtis Flowers, I fail to see a motive. Although the appeal doesn’t make this argument, it could be theorized that Doyle and his brother were paid to kill one of the four victims and, after making a botched job of the hit, ended up eliminating all the witnesses as well.

The appeal doesn’t go there because proving that Doyle Simpson was the trigger man isn’t the point of their argument. The law states that the state must not only prove its case against the defendant beyond a reasonable doubt, the jury must conclude that the state’s theory of the crime makes more sense than all the alternative explanations. In the appeal, defense counsel argues with effortless grace that Doyle Simpson makes a far more convincing suspect than Curtis Flowers.

It’s hard to argue.

The appeal brief makes the obvious point that if you believe one of the people who say they saw Curtis Flowers on the morning of the crime, you must disbelieve all the other witnesses. These people agree on virtually nothing and their testimony conflicts at virtually every point. I have spelled this out in my extensive blogging on this case and won’t repeat my argument here.

But the appeal demonstrates in detail how the state manipulated hapless witnesses. One woman was repeatedly brought in for questioning until she named Flowers as the man she saw leaning against Doyle Simpson’s car the morning of the murders. Her initial description of the man she purportedly saw bore no resemblance to Flowers. Since the woman was sleeping with Doyle Simpson at the time, it is likely that she invented her testimony out of whole cloth in a misguided attempt to stand by her man.

Thirty-nine days after first talking to the police, Porky Collins was asked to identify the man he saw in front of Tardy furniture shortly after the crime. Shown a picture containing Doyle Simpson, Porky said it might have been him. Then he was shown a photo array including the face of Curtis Flowers and opined that Curtis may also have been the man he saw. Only when one of the officers asked if he knew Curtis Flowers did Porky Collins make a definite identification. But at the first trial, he was again unsure if Flowers was the right man.

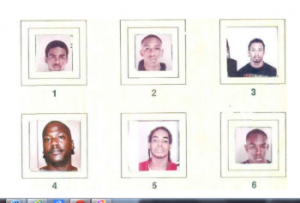

The confusion becomes perfectly reasonable when you see the photo array investigators employed. The other five Black men Porky Collins was shown were younger, had lighter complexions and different hairstyles than the man investigators were singling out for special attention. Not only that, they used a head-shot of Flowers while head-and-shoulders pictures of the other men were used. Finally, the picture of Flowers was of much higher resolution. If you don’t believe me, check it out for yourself:

I was also pleased to note that Flowers appeal brief accused Doug Evans of grossly misrepresenting the testimony of Sam Jones, the elderly Black man who was the first person to witness the horrific crime scene. Jones repeatedly insisted that he arrived at the store at 9:30 am, but Doug Evans suggested to the jury that Jones arrived half an hour later, at 10:00 am. The DA had several reasons for working this sleight of hand. Jones clearly testified that there was no bloody footprint when he arrived (he was adamant on this point) but that when he returned at 10:20 with the local police chief, the footprint was plainly evident.

In addition, a 9:30 arrival time would have meant that, if other witnesses are to believed, Flowers remained at the scene of the crime for up to forty-five minutes.

The Flowers appeal eviscerates Odell Hallmon, the man who was testified, at different trials, that Curtis Flowers confessed to him in prison and that he and his sister, the aforementioned Patricia Hallmon, invented their testimony because they wanted to cash in on the $30,000 reward. The Flowers appeal presents Odell Hallmon as the least credible witness to take the stand in the State of Mississippi since the Civil War (my characterization, not theirs).

Here’s an interesting comparison. Between 2003 and 2010, Odell Hallmon racked up almost four dozen disciplinary citations. In sixteen years of incarceration, Curtis Flowers has never been written up for misbehavior. Not once. And yet Evans sticks with his sordid witnesses because, without them, he has nothing on Curtis Flowers.

Prior to the 2010 Flowers trial, the defense team asked Max Mayes, a private investigator from Jackson Mississippi who had formerly put cases together for the Hinds County (Jackson) District Attorney’s office. Mayes reported that the Flowers case represented the worst single criminal investigation he had ever witnessed. The defense responded by asking Robert Johnson, the former police chief of Jackson, Mississippi, to appear as an expert witness. The trial judge refused to allow Johnson to testify, but in a special hearing outside the presence of the jury, Johnson left no doubt that his testimony would countered Doug Evans’ claim that the Flowers case was a model of investigative work. The judge, Flowers’ attorneys argue, got it wrong. They are right.

I have also argued that the single grain of gunshot residue purportedly discovered on the right hand of Curtis Flowers is meaningless, an argument that had never been made previously. At trial, the defense tried to get Dr. Jeffrey Neuschatz of the University of Alabama-Huntsville qualified as an expert on gunshot residue. Neuschatz was prepared to testify that one grain of residue on the hand of a man who had spent the day in a police car and a police office was to be expected and thus had no probative value. Once again, the trial judge refused to allow the testimony. Once again, the appeal says, he got it wrong.

It was harder to frame a Batson challenge (racial bias during jury selection) in Flowers 6 than in earlier trials. After James Bibb was charged with perjury after holding out for an acquittal in Flowers 5, he was accused of perjury. Eventually the Mississippi Attorney General’s Office took over the prosecution and dropped the charges for lack of evidence, but the damage was done. Black jurors made little attempt to hide the fact that they didn’t want to serve on the jury. But by dissecting the voir dire process, Flowers’ attorneys make a strong case that Doug Evans was just as determined to seat an all-white jury in 2010 as he had been when the Supreme Court sanctioned him for racial bias in earlier trials.

Evans badgered Black persons with distant ties to the Flowers family, but paid no attention to White persons who knew people close to the defendant. Evans knew that more than one Black juror would likely result in another hung jury, so he found a token Black person he knew would vote with the majority. So many Black members of the venire disqualified themselves and so many White jurors claimed they could be impartial even though they admitted having formed a strong opinion on the guilt-innocence issue that defense counsel couldn’t possibly eliminate them all. This argument is made in carefully researched detail and occupies at least a fifth of the appeal.

The resulting bias within the jury, the attorneys argue, is reflected in the 29-minute “deliberation”. Since it takes that long to deal with the procedural issues every jury confronts, there was no time for real deliberation at all, suggesting that the jury had reached its verdict before the first witness took the stand. When you get such a rapid verdict in a case this remarkably weak, the appeal argues, you have a biased jury by definition.

This explains why it was so important to show the Supreme Court justices that the state had a far more compelling case against Doyle Simpson than against Curtis Flowers. This fact was so obvious that only a biased jury could have missed it. Moreover, when state witnesses as comically compromised as Odell and Patricia Hallmon are taken at face value, the jury can’t be basing its verdict on the evidence presented at trial.

I was pleased to see that the appeal focused on the frequent conversation between jurors and local law enforcement during trial. The strange case of Lawanda Williams, a Mississippi College law student serving as an intern for the defense team, received the attention it deserves. On her way to the courthouse, Williams, who is Black, was pulled over by a White police officer who told her to keep her hands on the wheel and her eyes straight forward. When the professionally-dressed intern informed the officer that she was headed to the courthouse, she was told to drive straight there and to leave town as soon as the trial was over.

When this abuse of authority was brought to the attention of trial judge Joseph Loper, he accused the woman of inventing her story. This level of judicial bias shocked the defense team and is used in the appeal to demonstrate the degree of racial animus present in the courtroom.

The people responsible for perpetrating this judicial travesty on the good people of Mississippi have never been exposed to this kind of penetrating, relentless scrutiny in the seventeen years since Doug Evans arrived in Winona to investigate this case. Evans, who has close ties to the proudly racist Council of Conservative Citizens, came of age in a Mississippi determined to maintain white supremacy (their term of choice) at all costs. Evans imbibed this doctrine as a child but, unlike many White Mississippians, he has never questioned the culture that shaped him. It was so easy for the Granada prosecutor to convince himself that Curtis Flowers (or any other Black man in Winona lacking a good alibi) was guilty of the most shocking crime perpetrated in Montgomery County since two black men were sadistically lynched in the rural community of Duck Hill half a century earlier.

My parting comment is aimed at the journalists in my audience. Please give the full appeal your careful attention and ask yourself what would happen if this case was taken out of the hands of Doug Evans and turned over to the Mississippi Attorney General’s office. Is there even a slim possibility that, in such a scenario, Curtis Flowers would stand trial for an unprecedented seventh time. I can’t see it. Remove Doug Evans from the legal equation and this case crumbles under its own weight. It is that flimsy. And yet dozens of White jurors have chosen to convict. You have to ask why even if you don’t want to reckon with the answer.