This is the fourth segment of an ongoing series. You will want to checks out the first three segments before proceeding:

Five Days to Christmas

Five Conflicting Accounts

Mayhem and Memory

JeJuan Shauntel Cooks is a prisoner in the Eastham Unit in Lovelady, Texas. Ten years ago, he was sentenced to life in prison for allegedly firing two shots at a Milam County Sheriff’s Deputy. Cooks insists he couldn’t have committed the crime because he wasn’t carrying a gun.

Beathard arrives

By the time Jay Beathard arrived on the scene, a full hour had passed since shots were fired and Shaun Cooks was safely sequestered in a Hearne PD patrol car. Most of the officers who initially flocked to the scene had dispersed.

Beathard had been tasked with investigating the incident for the Sheriff’s department. He visited briefly with Sheriff David Greene before asking Chris White to walk him through the events of that evening. When he had the gist of the story, he says, he escorted White out of the crime scene and started looking for evidence.

Beathard likely found Taser wires stretched around the front end of White’s car. The Taser itself was lying on the passenger side of the vehicle. He found two shell casings from White’s gun. They were lying between 12 and 18 feet of the driver’s side of the police car’s trunk.

Next, he recovered the videotape from White’s dashcam. Then the big discovery; a semi-automatic handgun lying in a ditch. It was just a few feet from where the suspect had allegedly been lying when he fired two shots at officer White.

As we have seen, the evidence suggests that White was still in the throes of what police officers call an “adrenaline dump” (the technical term for this condition is Acute Stress Disorder (ASD). Because ASD can impact memory, it is likely that Beathard had a very hard time coaxing a coherent narrative out of his fellow officer.

But one thing was clear. White had no doubt that two shots had been fired at him at pointblank range. That’s why he asked the Hearne officers to check him for wounds when they arrived on the scene; he couldn’t believe that somebody could fire from such close range and miss. Twice.

And why, Beathard must have wondered, did the suspect stop firing after two shots?

Beathard’s dilemma

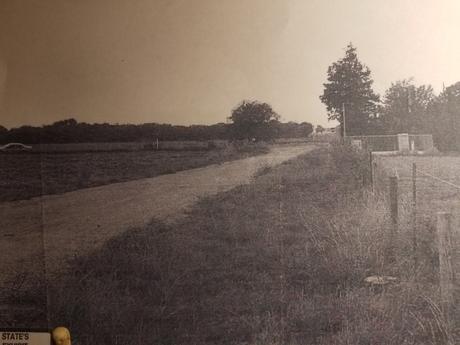

The photo above is an aerial shot of the crime scene. Most of the action took place within 150 feet of the intersection of FM 485 and CR 260. If White’s gun jammed, and couldn’t be found, the suspect might have tossed it. If a young, strong man grasped a gun by the barrel and put his full strength behind it, the gun could easily have traveled 150 feet. As the picture indicates, a large outcropping of trees stood less than 25 feet from the scene. For all Beathard knew, the gun could be anywhere within a 100-foot radius of the crime scene, and much of that territory was heavily wooded.

With the aid of a good metal detector, the weapon and shell casings could be recovered, but it would be a slow and tedious process.

If the gun hadn’t been lying there in full view, Beathard would have been in a tough spot. White was insisting that shots had been fired in his direction. Beathard believed him. So there had to be a gun. Somewhere.

The suspect had placed five lives at risk (including the life of a little baby) by fleeing a traffic stop at speeds in excess of 100 MPH; then he tries to murder a highly respect officer in cold blood. But after all that, he wouldn’t serve more than a year of two of State Jail time.

They had to tie Cooks to a weapon.

Planting a gun is serious business. In theory, if an officer is caught in the act, his career is over. But who would know?

Besides, the maximum sentence for shooting at a cop is 99 years. A Black felon who has already served serious prison time wouldn’t stand a chance at trial. And he’d know it.

Was Cooks incapacitated?

The Beathard-White narrative insists that, although White’s taser discharged, the defendant was never incapacitated. All the officers who testified at trial explained that a Taser fires two sharp probes which separate as they travel toward the target. To incapacitate a suspect, both probes must make contact, and they must be separated by at least four inches. One probe was found in Cooks’ jacket; the other, according to the Beathard-White narrative, was never found.

Cooks insists that he was Tased. Repeatedly. The second probe wasn’t found at the scene, he claims, because it was lodged in the small of his back. An EMS tech was summoned to the scene to remove the probe. The wound was bleeding so badly when he arrived at the Milam County Jail that he had asked for medical attention.

There are two good reasons why the Beathard-White narrative has no room for a Tased suspect. A man who is incapacitated by a taser, can’t roll over and fire a gun. And he can’t run. The Beathard-White narrative has Cooks doing both these things. White testified that one or both of the taser probes must have missed their mark. But is this likely?

On the dashcam tape played at trial, White can be heard telling first responders that “I saw he had a gun, so I tased him.” He might have said, “I thought he had a gun” (the trial transcript includes both versions and I don’t presently have access to the tape). Asked about this at trial, White said he had misspoken, but this is unlikely. The statement was made spontaneously, without reflection. This close to the action, White wasn’t thinking about creating a coherent story for a jury.

Secondly, a tased person will normally recover full functionality as soon as the taser stops cycling. White emphasized that, after fleeing for cover, he repeatedly pulled the trigger of his taser. If the taser probes found their mark, Cooks would have been tased repeatedly. Repeated Tasing is a much debilitating than taking a single jolt. After being arrested, Cooks says, officers had to drag him to a police car because his legs couldn’t support his weight.

The origins of the 9mm story

Legality aside, there are several downsides to planting a gun. There would be nothing but the officer’s word to connect the weapon to the suspect. You couldn’t run standard forensic tests on the weapon because the suspect hadn’t touched it. There would be no gunshot residue (GSR) on the weapon or on the hands and clothing of the suspect.

But since cases like this almost never go to trial, that was a small risk. Besides, if a defense attorney asks why every investigative protocol in the book had been violated, you could just say it wasn’t necessary. Turn the trial into a swearing match between a Black drug dealer and a Sheriff’s deputy and there is nothing to fear.

A third possibility

The gun could have been placed next to the fence by the suspect or by Jay Beathard. Or, it could have been dropped by any one of the dozen-or-so officers who flocked to the scene.

White testified at trial that, as he waited for Beathard to arrive, he visited with his fellow officers with the Milam and Robertson County Sheriff’s departments and from the Hearne and Cameron police departments. White related to most of these men on a first-name basis. He told them that the suspect had fired two shots at him. He asked them to check to make sure he hadn’t been wounded. He showed them where Cooks was lying when the shots were fired.

These men were angry. Someone had tried to murder one of their own.

All these men were on the lookout for the Twilight rapist, purportedly a young Black man with an appetite for white women. The guy in the Hearne PD patrol car might not be the Twilight Rapist, but he had been with two young white women. According to Cooks, several comments to this effect were made while he was being taken into custody, at the County Jail, and by Beathard himself.

The officers at the scene were familiar with the suspect sitting handcuffed in a Hearne PD patrol car. Over the past three years, Cooks had been stopped repeatedly by officers in his home town of Hearne who were hoping to find drugs in his possession. His home had been searched repeatedly. Traffic stops were a routine occurrence. The police always came away disappointed, which is why DA John Paschall, the reputed boss of Robertson County, used a confidential informant to plant drugs in Cooks’ vehicle.

But where was the gun?

All the officers at the scene possessed motive and opportunity for planting evidence. They all knew an investigating officer was on the way but would be delayed in arrival. How easy it would have been to drop a throw-down gun where J. Beathard was sure to find it? The Cooks-White incident happened less than ten minutes from Hearne. So, there was even time for an officer to leave the scene, drive to Hearne, fetch a throw-down gun, and return before Beathard arrived.

No shell casings from the 9mm weapon were ever found. It was dark, of course. Very dark. But a good flashlight and a half-decent metal detector could easily have found any brass casing within 20 feet of the spot where the shots were allegedly fired. Beathard didn’t bring a metal detector with him. When he returned to the scene a few days later in the light of day, he still didn’t have a metal detector with him. How do we explain this lack of interest in finding the shell casings from the 9mm?

According to trial testimony, Officer Doug Veach assisted Beathard in his investigation. Veach would have been an excellent corroborating witness for Beathard, just as Shawn Sayers, the Hearne officer who made the actual arrest, could have corroborated White’s testimony. Neither man was interviewed or subpoenaed to testify. Was this a cost-saving measure; or was Beathard worried that Veach and Sayers might contradict the official narrative?

There is an unwritten law that cops don’t testify against fellow officers. It’s a feature of the thin-blue-line philosophy. Once you’re in the brotherhood, your back will be covered. You will rarely hear two police officers present conflicting testimony at trial. They agree on a common narrative, and they stick to it.

What about the video?

If, as I argue, there was only one burst of gunfire that night, and if all the shots emerged from the barrel of White’s .45, why are their two bursts of gunfire, separated by thirteen seconds, on the tape introduced into evidence at trial?

According to White’s testimony, just a few seconds elapsed between the shots Cooks fired at him, and the shots he fired at Cooks. Although he didn’t see the gun, White says he heard two shots. He fled behind his patrol car, repeatedly pulled the trigger on his Taser. Then, when he saw Cooks running back across the pasture in the direction of the Mercedes, White reached for his .45 sidearm fired two shots at Cooks. Cooks fell to the ground with both hands exposed. Meanwhile White stood fifteen feet away calling for backup. This action unfolded very quickly; which is why only 13 seconds separate the shots fired by Cooks 9mm from the two shots White fired from his .45. (To get a visual picture of this testimony, check out the picture immediately above this paragraph. Cooks would have been lying about halfway between the “260” marker and the red location pin when he allegedly fired his weapon. The Mercedes would have been parked at the central “485” marker.)

In the second segment of this series, I mention a phone conversation with Shawn Sayers, the Hearne PD officer who actually arrested Sean Cooks. Sayers insists that he didn’t head for the crime scene until he heard White saying over the radio that shots had been fired. But when Sayers arrived at the intersection of 485 and 260, the suspect wasn’t on the ground, he was up and running. And he wasn’t running toward the Mercedes, he was running parallel to the fence (again, checking out the arial photo will help). If Sayers’ memory is accurate, White must have remained behind his police car for at least a full minute. And, if he was pulling the trigger of his Taser every five seconds, Cooks would have remained incapacitated until White dropped his Taser and pulled his .45 side arm.

But according to the video introduced at trial, less than fifteen seconds elapsed between the first two shots, from Cooks’ 9mm, and the second burst of gunfire from White’s .45. If Sayers has it right, that tape has been altered to fit the Beathard-White narrative.

Even if they had been inclined to tamper with the tape, did White and Beathard possess the technical chops to make it happen?

According to trial testimony, the VHS tape removed from White’s Mobile Vision dash camera was converted to DVD format before being shared with the District Attorney, the defendant and defense counsel. This was standard procedure at the time. Some of the cars used by the Sheriff’s department already had digital recorders, but White’s patrol car didn’t.

In the early days of 2010, machines designed to transfer analog VHS tape into a digital DVD format (or vice versa) were a practical necessity. You can still buy one new for around $150 or pick up a used unit on eBay for much less (but why would you?) The Sheriff’s department had such a machine. Until the dash cameras in all the patrol cars had converted to a digital format, it was a practical necessity.

Suppose the VHS tape revealed only a single burst of gunfire? For Beathard, that would have been inconvenient. And easily remedied. Once the recording had been transferred into digital format, it could be altered endlessly. (If you doubt me, this YouTube video from 2012 shows how easy it is.) One burst of gunfire could become two by copying the initial sound and pasting the sounds at a later point in the recording. Any inconvenient sounds could be eliminated with the click of a mouse. A duration of over a minute could be reduced to 13 seconds by simply cutting out a period of the recording. The second burst of gunfire could be muted, or enhanced, at will to make it sound as if two different guns had been fired.

You could even transfer the resulting tape from DVD back to VHS if you wanted to.

This certainly doesn’t prove that Beathard and White did any of these things; but it would have been a task any ten-year-old could manage.

Mr. Cooks has always maintained that the entire video is a reenactment. It had been raining the night of the incident, he says, and the field was soggy. But in the video introduced at trial, he says, dust can be seen trailing from White’s car as it drives across the field.

Since I don’t have a copy of the tape from White’s car, I can’t speak to any of that. But tiny modifications to the tape would have produced the desired effect.

Remember that White’s vehicle stopped within a foot or two of the fence. The only thing visible on the video is the portion of the pasture on the far side of the fence that was illuminated by the car’s headlights. Since the picture didn’t change throughout the video, alterations to the audio would have been unnoticeable on the video.

The long version of the tape

The tape didn’t stop running when Mr. Cooks was handcuffed. As previously noted, up to a dozen officers, from four separate jurisdictions, were on the scene. They were chatting with White and one another, before Beathard removed the tape from White’s patrol car and much of this conversation was captured on tape.

Cooks says that, as he was being led to the Hearne PD vehicle, a Hearne PD officer announced that, if he had made the arrest, Cooks would still be lying in the field. Other officers, Cooks says, told the officer to be quiet.

Cooks’ story can’t be corroborated, but, under the circumstances, it is easy to imagine something of the sort being said. The conversation recorded on tape was almost certainly angry, violent, vulgar and blatantly racial. The kind of talk sure to raise questions.

What if the longer version of the tape-recorded eyewitnesses like Sayers, and possibly White himself, describing the scene in ways that diverted from the official narrative?

Whatever was on the longer version of the tape, Beathard and White fought hard to keep it from the ears of a jury.

A rare occurrence

Officers are killed in the line of duty much less often than you might suspect. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, only fifty-five police officers were killed in the entire nation in 2010 (which is as close to late 2009 as I can get). Forty-seven of these murders were committed by white males, seven by Black males, and one by an Asian male.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, law enforcement is the eighteenth most dangerous occupation with a fatality rate of 13.1 per 100,000 officers.

In the entire United States, in the five years between 2015 and 2019, a total of four (4) police officers were shot and killed while trying to arrest and cuff a suspect. That’s one a year. In 2016, this killed-while-making-an-arrest scenario didn’t play out a single time in the entire United States.

If Cooks tried to kill a police officer in 2009, he was committing a crime that is vanishingly rare.

A broken chain of custody

Officer White was both the chief witness against the accused and, disturbingly, the custodian of the evidence room for the Milam County Sheriff’s department. Most significantly, White had custody over the dashcam video. At trial, Officer Beathard testified that he took custody of that video at the scene. Fair enough. But at some point, likely the next day, he delivered the tape to the person in charge of the evidence room: Chris White.

At trial, defense counsel didn’t need to prove that JeJuan Shauntel Cooks was innocent. The burden of proof belonged to the state. Defense attorneys just need to muddy the waters by creating a credible counter-narrative. As this segment makes clear; that wouldn’t have been difficult. But it didn’t happen.

Why? That’s for next time.