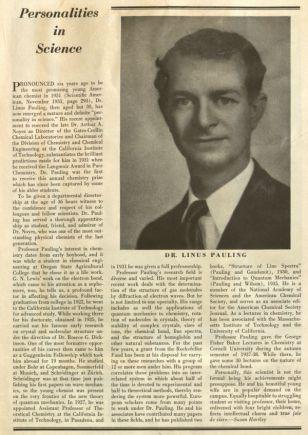

[Pauling as Administrator]

With its brand new building and innovative, well-funded research program, the Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering at the California Institute of Technology, under the leadership of Linus Pauling, was increasingly coming to be recognized as a model for chemistry departments and divisions around the country.

This boost is stature is clearly evident in Pauling’s correspondence. In one instance, John C. Bailar, Jr., Assistant Professor and Secretary of the Department of Chemistry at University of Illinois, Urbana, wrote to ask about ways in which they could follow Caltech’s model to improve their own research and instruction. Likewise, Joseph George Cohen, Director of the Division of Graduate Studies at Brooklyn College, noted his ambition to “pattern [their] administrative practices on those schools which occupy a position of leadership in American Chemistry,” and asked how Caltech ran its laboratories and what responsibilities they gave to their PhDs and graduate assistants. Pauling was always willing to give his advice.

Pauling’s recommendations were also commonly sought by other programs looking to hire new staff. Although his picks were not always a match, Pauling increasingly found himself in a position to influence the shape of research around the country. During the fall of 1938 for instance, Pauling recommended a professional colleague, Gilbert King, to fill a position at Duke University. King ended up going to Yale and then MIT instead. After learning that King would not be coming, Paul Gross of Duke again reached out to Pauling, asking for another name.

Lindsay Helmholz

This second time around, Pauling leaned more heavily on his role as division chair and began advocating for an up-and-comer within the division. This individual was Lindsay Helmholz, whom Pauling described as “one of our best men.” Though he was reluctant to lose Helmholz’ skillset, Pauling worked hard in selling him to Gross, highlighting his research and teaching skills while also emphasizing the range of material that Helmholz was familiar with, including topics in physical, structural, and general chemistry. Pauling further pressed Gross to offer Helmholz a permanent position, as he would be more likely to accept it. For added measure, Pauling noted that “Dr. Helmholtz is married to a very pleasant and attractive young woman, and I am sure you would consider the Helmolzes an addition to your community.”

Helmholz ended up not going to Duke, leading Pauling to recommend him again the following summer to Elden B. Hartshorn of the Department of Chemistry at Dartmouth College. Pauling once more praised Helmholz’ ability to teach advanced courses and lauded his experimental and theoretical research skills. And as with his communications to Paul Gross, Pauling concluded with more personal information

Dr. Helmholz is a pleasant and cultured young man and is married to a pleasant and cultured young woman. His father is head of the pediatrics division of the Mayo Foundation at Rochester.

Hartshorn responded that they were looking for someone for the following year and hinted that they may not have the facilities to support Helmholz’ research. Helmholz ultimately ended up at Washington University after working on the Manhattan Project during World War II.

Pauling saved his second-tier recommendations for less prestigious institutions, like the Department of Chemistry at his alma mater, Oregon Agricultural College. In this instance, F.A. Gilfillan, Dean of the School of Science at OAC, was looking for teaching fellows in 1939 and was eager to receive any ideas that Pauling might have in mind. In response, Pauling recommended Robert J. Dery, who had taught at Caltech for three years but had not completed his doctorate since he seemed “for some reason to lack the ability to carry on experimental research.” Dery, according to Pauling, was also “slow spoken, so that in conversation with him one may become impatient.” This habit did not affect Dery as a teacher however, as he spoke very well in front of an audience and, in Pauling’s estimation, was a good freshman instructor.

By April 1939, as the funding from the Rockefeller grant approached its second year, Pauling and Warren Weaver were still looking for someone to head biochemical research being supported by the grant. Pauling asked Weaver if he might further delay the hiring as no clear-cut match for the position had been identified. That June, the Rockefeller Foundation’s Board of Trustees, while discussing the following year’s budget, noticed that no one had been hired and questioned the need to approve the full $70,000 request for the following year. Ultimately the board agreed to the original request, but their hesitation to do so led Pauling to scramble.

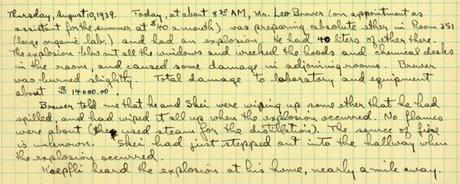

Pauling’s notes on the August 1939 explosion. Note in particular his closing sentence: “Koepfli heard the explosion at his home, nearly a mile away.”

In the meantime, Pauling continued to deal with the more mundane responsibilities that were assigned to him as chair. These included a wide range of hiccups presented by the move into the new Crellin Laboratory. One specific issue was the need to make sure that graduate students could access particular areas of the facility – most pressingly the student shop – that were normally only open during business hours. To solve the problem, Pauling requested that a lock be made for the shop that matched the locks on Crellin’s entry doors so that the students could enter more easily.

A much larger problem came to pass in August 1939, when a spark from a ventilating system motor ignited six liters of spilled ether in Crellin Room 351. Leo Brewer, who was in the room at the time, had been working with a twelve liter flask of ether on a ring stand. When he went to adjust the position of the flask on the stand, the bottom fell out of the flask. Brewer cleaned up the ether as best he could, but about five minutes later, as he wrote in his incident report, “suddenly there was a flash of fire which singed my hair, face, and hands.” He immediately left the room and “five seconds later there was an explosion which rocked the building” as the hoods sucked up the flames, igniting the ten gallons of ether in them. Students and stockroom workers equipped with gas masks and fire extinguishers combated the flames until firefighters arrived. In the midst of it all, a second explosion knocked over acid bottles, leading to reactions that produced poisonous gas. All told, the damage was assessed at $13,924.22 (the equivalent of more than a quarter-million dollars today).

Laszlo Zechmeister with the Pauling family, 1940.

While dealing with all of Crellin’s issues, Pauling also had to respond to increasing pressure from the Rockefeller board to find someone to head biochemistry research within the division. The more he thought about it, the more Pauling leaned toward hiring Hungarian chemist Laszlo Zechmeister, who had visited the previous fall. While current staffer Carl Niemann had shown promise, Pauling thought him too young to head the fledgling biochemical research program. Zechmeister, who was in his fifties, was arguably too old, but Pauling began to see his age as an advantage since he was certain someone would emerge from within Caltech itself to lead the program over the next ten to twenty years.

Zechmeister had maintained a correspondence with Pauling since his visit, keeping him informed in particular of Hungary’s increasingly close relationship with Nazi Germany. Zechmeister also told Pauling that, if there were a position available for him elsewhere, he would take it immediately. Pauling finally offered Zechmeister a professorship in organic chemistry in October 1939, which was quickly accepted. The only sticking point was that the contract needed to stipulate that the appointment was for one year only, as that was the longest period of time that Zechmeister was legally allowed to leave Hungary. Sadly, Zechmeister’s wife became sick before they came to Pasadena in 1940, and died the following year. And ultimately Zechmeister would not return to Hungary, spending the remainder of his career at Caltech.

Just two and a half years into his tenure as Chairman of the Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering at the California Institute of Technology, Pauling saw to completion a variety of plans originally set in motion by his predecessor A.A. Noyes, including the construction of a new building. With the onset of the Second World War, an influx of federal funding would create new opportunities as more researchers and projects filled out the division’s buildings. With observations made and lessons learned along the way, the war would also set the stage for Pauling to build off of what he had inherited and take the initiative in further shaping the division.