Kiya Babzani, co-owner of the specialty denim empire Self Edge, is mostly hush about who patrons his stores, but he shared as story once of the most unlikely of customers. One day he received an order for a few things from Flat Head and Iron Heart. Having run the credit card a few times and getting the charge declined, he became suspicious of fraud. So he looked at the customer’s delivery information – Owenscorp in Paris – and reached out. “Oh it’s for Rick,” the buyer explained. “Sorry if the credit card didn’t go through. He wants these things sent to his studio."

Rick, of course, refers to Rick Owens, who is reverently known to his fans as the “Lord of Darkness.” His clothes are masterpieces in terms of pattern making, far surpassing anything you’d find on Savile Row, but they’re cut for the clinically underweight. The shoulders are narrow, sleeves tiny, and chests tight. If you can somehow muscle your way into his clothes, however, they become beautiful, black coiling sculptures. Owens drapes and twists materials such as beaten lambskins and silky cottons to create garments that look like they’re decaying monastic robes in some space-age Brutalist future.

What brought Rick Owens to Self Edge? The thing that unites almost every American clothing experience: the hunt for the perfect flannel shirt. Owens found his in the form of a red buffalo check flannel from Iron Heart, but then lost it a year later. His assistant emailed Kiya again, asking if he had another (“it’s his favorite,” she pleaded). Kiya didn’t, but found the same model in blue. "No worries, just mail it. We’ll dye it,” she replied. Of course, that’s impossible. Once a check has been made, you can’t change it into a different color because the yarns have already been woven. But who’s going to question Rick Owens’ garment making techniques – or deny him of his favorite flannel?

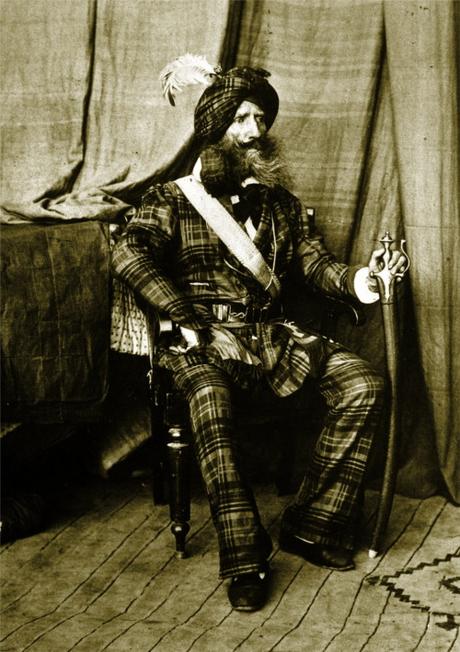

After blue jeans and white t-shirts, few things define American wardrobes as well as plaid flannel shirts, but they didn’t start here. Instead, they take their patterns from the Scottish Highlands – tartans, in other words, which at one point were considered so dangerous that the British parliament banned them as part of the Dress Act 1746. This was shortly after the Highland clans were defeated in the Second Jacobite Rebellion. Fearing that any outward showing of Highland pride would lead to more uprisings, parliament banned wearing tartans at all outside of military use. “To put it in modern parlance, they would be seen as terrorists,” said historian Peter MacDonald in an Articles of Interest podcast episode. “Or freedom fighters, depending on which side you were on, but that was the reason for the ban.”

Much like how banned books become the cool thing to read, banned plaids became the cool thing to wear. In the decades following the Dress Act, there was a romantic revival of all things Highland, particularly among people who lived outside the region. Suddenly, people across the Borders and in England started wearing tartan. And when Parliament finally gave up and repealed the Dress Act, these colorful plaids migrated to India, where they were remixed with local dyes and transformed into colorful madras. Those in North America, of course, also started wearing tartans as part of their daily dress.

Some of the first people to start wearing tartan in the Americas didn’t do so willingly. They were the African slaves of Scottish plantation owners in the West Indies. It’s ironic since many of these Scots didn’t choose their life, but had it imposed on them by the Scottish and English courts, which threw them out to the islands for committing crimes. “The Highlander was an object of hatred to his Saxon neighbours,” Lord Macaulay once wrote in his History of England. “When the English condescended to think of him at all, — and it was seldom that they did so, — they considered him as a filthy abject savage, a slave, a Papist, a cutthroat, and a thief.”

Like other plantation owners, the Scots in the West Indies made fortunes off of farming, largely because they didn’t have to deal with the nuisance of actually paying for labor. They often dressed their slaves in their cast-off clothing – partly to save on additional clothing costs, but also at times to show off their wealth (the livery of house slaves were often of better quality than those worn by field workers, and some wore the sort of tartan dresses you see above). There was another reason to force slaves into wearing tartan. Since slaves were considered property by the state, runaways were often identified by the uniqueness of their livery – as their tartans were often specific to a plantation or family. So, if and when captured, they were then sent back to their owners. The film 1745 by the Akande sisters, Moyo and Morayo, explores some of this painful history.

In the same Articles of Interest episode, Avery Trufelman talks more about the history of these plaids. They’ve become integral to a certain kind of working class uniform, which has been since remixed by punks, queers, and hipsters. The start of the episode has a funny anecdote by Anna Pulley, a writer who said she didn’t know who should could hit on anymore when she moved from Chicago to San Francisco (the second being a city where almost every office looks like a sawmill). When I talked to Frank Muytjens a few years ago, he said that he incorporated the lumberjack look into J. Crew’s catalog because he liked how lesbians wore the style – buffalo check shirt, Red Wings, and all – in New York City’s hip Chelsea district.

For a blog called Die, Workwear, I have a surprising number of plaid flannel shirts. Dressier ones, such as those from Portuguese Flannel and Proper Cloth, go great with chunky Arans, heavy tweeds, and waxed cotton Barbours. More substantial varieties, on the other hand, are natural accompaniments with workwear. In the right material, these can be so comfortable that they can even double as pajamas. I’ve tried over a dozen brands over the years, which I thought I’d list here and review. Hopefully you can find your perfect flannel somewhere in this list.

Uniqlo

I’m generally a fan of Uniqlo. The store is great if you want reasonably well-made basics at affordable prices. Their flannels for me, however, have been a disappointment. I bought a couple back in 2014, but they’ve since seen little wear. Most of the time, I prefer to reach for beefier fabrics. Uniqlo’s are good in that they’re affordable, often available on sale for a little more than $20, but they suffer in terms of weight. These are soft, but thin, and a little closer to your standard dress shirts made with tartan patterns. Wear these if you want the look of a flannel but don’t expect much warmth. For affordable options, I would sooner check out Vermont Flannel and Duluth Trading instead. I haven’t tried those myself, but they garner good reviews online.

J. Crew’s Wallace & Barnes

J. Crew’s Wallace & Barnes is one of the best values right now in menswear. The clothes have more of a boutique feel than J. Crew’s mainline, are made from better materials, and are inspired by vintage pieces that Frank Muytjens and his team once collected for the company’s archives.

I particularly like their flannels. Their earlier fall versions are a bit too lightweight for my taste, but the heavier winter varieties are nice and substantial (look product descriptions that use the term heavyweight). Like many of Wallace & Barnes’ workshirts, these are triple-needle constructed and have a chambray lined yoke to help with durability. They’re wonderfully thick and sturdy, but are also soft enough to wear without an undershirt. They run a little full, however, so size down if you want a slim fit. For under $100, these feel like the kind of good, honest basics that have mostly disappeared from the market.

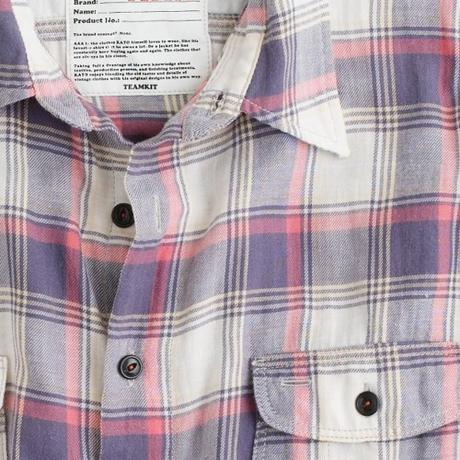

KATO Brand

Some readers may remember KATO from J. Crew’s “In Good Company” section. Their cream and purple flannel, pictured above, appeared many years ago as part of the mall outfitter’s online selection, back when acquiring Japanese goods was still rare for many people. They’re harder to find now that they’re not longer at J. Crew (most of their distribution is in Japan), but worth a look if you can track something down.

The company’s designer, Hiroshi Kato, is passionate about classic Levi’s workwear, which is why you see so many vintage-inspired details here – cat eye buttons, curved chest pockets, and chainstitch runoffs. But unlike other vintage workwear companies, KATO’s shirts still feel contemporary, fitting in just as well with Engineered Garments as they do with Club Monaco. Their fabrics, while often a little flimsy, are also extra soft, I imagine because they’ve been put through an enzyme washing process. This may be because KATO’s parent company also owns one of the largest denim manufacturing and washing facilities on the West Coast.

RRL

Like other designer lines, it’s hard to characterize RRL’s flannels because they change from season to season. Some that I’ve bought are close to the sort of loose-weave, substantial work shirts that you might find at a flea market. Others are a bit more akin to an average mall-branded shirt, but made with better finishing and trims. Either way RRL is always worth a look. Ralph Lauren’s team has the design experience and production scale necessary to offer the kind of unique weaves and finishing processes that can be hard to get from boutique lines. The two shirts above, for example, have been washed in a way to achieve an uneven color.

RRL’s flannels are often a little trimmer through the waist than others on this list, but they’re reasonably forgiving. They also come in the kind of plaids that I think are easier to combine with workwear. Less Barbour; more ranch jackets and chore coats. And while they’re not inexpensive, they’re well-priced at around $185 at full retail. You can find them at Mr. Porter, END, Stag Provisions, Canoe Club, and Ralph Lauren’s own site. For other vintage-styled flannels, check out Levi’s Vintage Clothing.

Gitman Vintage

Like with RRL and Wallace & Barnes, I wish Gitman Vintage’s flannels were a little shorter. Actual vintage flannels, particularly those from the immediate post-war period, are nice in that they’re short and come with a square hem, which makes them easier to wear untucked. Many of the more modern varieties of vintage styles, on the other hand, come with a gently curved hem and mid-way length that sits somewhere in no man’s land – too long to wear untucked, but not properly long enough to actually tucked. Depending on your outerwear, you may want to go with something else.

Still, Gitman Vintage is nice in that they’re solidly constructed and made in the USA (if that matters to you). They also have a classic Americana look that makes them easy to wear with more classically minded wardrobes. This season, they have a triple yarn construction that I think look really handsome. You can find them at Division Road (a sponsor on this site), Unionmade, BlackBlue, Mr. Porter, End, East Dane, Need Supply, and Gitman’s own site. Corridor is also worth a look if you’re into this kind of thing.

Nigel Cabourn

Nigel Cabourn’s critics like to say that his collections don’t change enough from year to year – and it’s true, but I think that’s a good thing. Cabourn makes clothes inspired by vintage military and mountaineering gear. They’re functional, handsome, and carefully considered. My Surface parka, which I bought from the company many years ago, is still one of my favorite pieces of outerwear. Since Cabourn doesn’t feel the need to wipe the slate clean and begin anew every season, you’re often still content with your purchases many years after purchasing them.

Every winter, he releases a small collection of flannels to go along with his workwear. One of my favorite pieces from him is a reversible design with a heavily brushed underside. I almost never wear the brushed side out – it’s too comfortable against the skin – but it’s a nice, heftier flannel that can almost double as a shirt jacket. My only quibble is that the smoked mother-of-pearl buttons feel a little out of place on such a rugged garment, but the fabric is so thick that perhaps proper work-style buttons wouldn’t do. You can find these on eBay.

Five Brothers

Five Brothers used to be an American manufacturer of genuine workman shirts and you can still find their flannels second-hand. The ones I’m talking about, however, are the Japanese versions that are made for the fashion market. They’re a little trimmer and a lot shorter. And while the cotton doesn’t age that well – it gets stiffer and rougher with each wash, rather than softer – I love their vivid colors, hefty triple-yarn construction, and unique designs. Hunky Dory has some good photos of their shirts.

Context Clothing and Hickoree’s used to carry Five Brothers flannels, but it looks like they no longer do. You can sill find them, however, at Rakuten (an online marketplace that connects Japanese sellers with overseas customers). It can take a while to figure out how to shop on Rakuten, but this YouTube tutorial helps ease you through the process. These flannels are a solid value at $70 and probably the best option if you prefer a shorter silhouette to neatly sit under cropped jackets.

Pure Blue Japan

Pure Blue Japan’s sunburned work shirt is perfectly suited for the work of Adobe Illustrator jobs and cubicle farming. To be sure, the best sunfaded work shirts are always going to be the ones with authentic wear patterns, but if you, like me, never actually get to see the sun, then this pre-distressing is pretty convincing. The shirt is slimmer fitting than actual vintage varieties, while having the kind of worn-in look that makes workwear outfits charming. And while again not inexpensive at $290, I find I wear mine all the time. The one I bought is the version you see above, which is now unfortunately sold out, but this ever-so-slightly different plaid serves the same purpose.

The only thing I don’t like about the shirt is the odd button placement on the left chest pocket, but if you unfasten the button, only the buttonhole shows and it’s mostly unnoticeable. You can see how it looks when worn at Blue in Green’s Instagram.

John Lofgren

John Lofgren, a favorite in the workwear scene for his boots and sneakers, used to have flannel shirts. I own the one pictured above, which was released many years ago as part of the company’s clothing collection. Unfortunately, he no longer makes apparel under his own line, but he recently produced two shirts for Eastman. I haven’t handled those, but from photos, they look similar to the shirt I own. And if so, you can expect the fabric to be comfortably soft, but also have a slightly coarse, dry texture that gives it some rugged appeal. There are lots of vintage-inspired details here, such as the chin strap, cat-eye buttons, and extra stitching around the pockets. The style has a repro feel that allows it to sit well with other vintage-styled workwear.

Indigofera Norris

Colors just look like colors when you’re shopping for clothes, but how those yarns were dyed will determine how they age. Reactive dyeing, for example, is a process that results in longer lasting and deeper colors. Iron Heart calls their reactive black denim jeans “Super Black” because they don’t easily fade. Alternatively, yarns can be treated to sulfur or acid dyeing (the first is typically used for cotton, while the second is reserved for wool). These techniques are usually less expensive, but the colors are less brilliant and fade easily. This is why, when you have two black shirts, one can look dull and dingy after a few washes, while the other looks as deep in color as the day you bought it.

Smart designers like the ones behind Indigofera, however, know how to use sulfuric dyes to their advantage. The company has tons of great flannels, such as their kitten-belly soft Byrson and sturdier, heavyweight Dawson. My favorite from them is their Norris. These are buffalo check flannels made from a 3x1 twill weave. And since the darker yarns have been treated to indigo or sulfuric dyes, they fade like your jeans. In the photo above, you can see how their indigo shirts age over time. They have the same design in khaki-and-charcoal, as well as green-and-black. You can find these at Standard & Strange, Rivet & Hide, and Pancho & Lefty. Just be sure to size down.

Flat Head

Far and away, my favorite flannels are from Flat Head. A couple of years ago, they had something they called their “Winter Wear” line, which was distinguishable by the clothing label you see in this post. The fabrics were heavy, about 12 ounces, I’d estimate, and triple brushed on the reverse side. The result is one of the best feeling flannels you could ever put on. They’re made in a rugged workwear style, no less, but they’re somehow more comfortable than six-ply cashmere sweaters or brushed-cotton dress shirts. You can even use them as pajamas, as I sometimes do.

Unfortunately, the “Winter Wear” collection looks like it’s no longer around, but the company’s expertise in fabrics remains. I really like the turquoise check this season, pictured above. “The patterns are created with vintage shuttle looms, which can do a proper slack weave,” Kiya of Self Edge explains. “That gives their fabrics a more three-dimensional look.” The only thing to watch out for are the many, and often confusing, sublines. Flat Head’s mainline flannels are inspired by the patterns and details of work shirts from the 1950s, while Glory Park takes after those shirts that came a decade later. Kiya admits: “They change the branding and naming of their flannels every few years, and honestly it’s hard for most retailers to even keep up with their (mostly) nonsensical naming structure.” So long as the main company is Flat Head, however, you can be assured the flannel is really good. You can find them at Self Edge, Rivet & Hide, Tate + Yoko. Note, for these, you’ll want to size up.

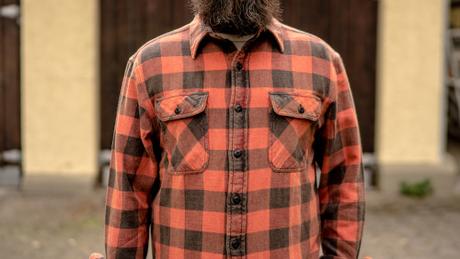

Iron Heart’s Ultra Heavy Flannels

Since Flat Head’s “Winter Wear” collection is no longer around, the next best option is Iron Heart’s ultra-heavyweight flannels. Like those from Flat Head, these are made from an uber-thick 12oz fabric with a heavily brushed underside. They also come with felled seams, which I find to be more comfortable to wear against bare skin, and are smartly designed without a clothing label at the neck, which could otherwise irritate the skin. The heavy brushing inside not only helps trap heat, but also blocks wind. These flannels can be a little starchy at first, but they soften up wonderfully over time.

Their only limitation are the designs. Iron Heart specializes in a particular kind of workwear aesthetic with a motorcycle edge. These flannels have Western style yokes, which I find look better with certain clothes than others (good for heavier ranch and motorcycle jackets, but looks off to me under chore coats). They’re one of the priciest flannels on this list, although if it matters to you, they also have the best resale value. Frankly, I’m amazed it’s so hard to find anything comparable in terms of construction. These seem like the sort of quality work shirts that should be offered by traditional workwear manufacturers, but I haven’t found anything as sturdy or comfortable. Maybe that’s why even Rick Owens is a convert.

You can find Iron Heart’s flannels at Division Road, Self Edge, Rivet & Hide, Canoe Club, and Iron Heart’s own store. They run very trim, so consider sizing up.

Shopping Vintage

In a talk with The Fashion Law, Courtney Love once said of the Saint Laurent FW13 collection: “It reminds me of Value Village. Real grunge. I love that rich ladies are going to pay a fortune to look like we used to look when we had nothing.” The quote reminds me of how, if for no other reason than authenticity, the best flannels are often vintage.

For a good vintage flannel, try scouring local thrift stores, eBay, and Etsy for names such as Big Mac, Big Yank, and Big Mike (there were a lot of “Big” labels back in the day). Frostproof and Five Brothers are also great, the second of which was mentioned above. If you’re looking for a more curated selection, Wooden Sleepers in Red Hook, Brooklyn would be my first stop. Their store is pictured above, as well as at the very top of this post. You can shop at their selection at their brick-and-mortar, online shop, or Instagram. They take phone orders.

The often-touted signs for what determines a good garment are frequently overstated, but they hold pretty true for vintage apparel. Second-hand flannel shirts are often better if you can see a made-in-USA tag. It’s also generally a good idea to stick to natural fibers, such as pure cotton or cotton-wool blends, rather than anything mixed with polyester. And it helps to look for old-school details such as cat-eye buttons, chin straps, and chainstitch runoffs. These alone won’t make for a great flannel, but they get you closer to something that looks special instead of mass-market.

Since buying second-hand can be dicey, look carefully for hidden snags, holes, and coffee stains, which can be particularly hard to spot on busier designs. One trick is to hold something up to the light to see if anything shines through. If you’re buying online, triple-check measurements. The fit on these things can vary wildly, even within the same label. Flannels don’t need to fit perfectly, but they should be within the ballpark.