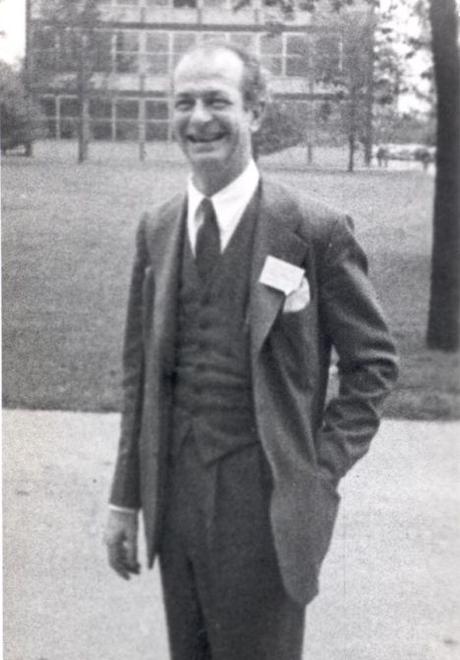

Linus Pauling, 1949

Linus Pauling, 1949[Exploring Linus Pauling’s popular writings on the shape of post-war science, part 4 of 5.]

“Our job ahead.” Chemical and Engineering News, January 1949

The onset of 1949 brought with it the beginning of Linus Pauling’s one-year term as president of the American Chemical Society, and Pauling’s article “Our job ahead” outlined the message that he wished to convey to the society. In it, Pauling specifically addressed the financial concerns being faced by the ACS as well as the scientific community at large.

The society’s problems centered on the need to manage operating costs and member remunerations in the midst of rising costs of living. More broadly though, Pauling saw for the society a responsibility to try to improve financial conditions for science as a whole. Pauling argued that the destruction of war, in tandem with the massive consumption of natural resources required by the war effort, had resulted in increasing levels of poverty throughout the world. Pauling encouraged the ACS to do its part to combat the problem by supporting and participating in global interdisciplinary scientific cooperation.

Pauling also pushed for ACS support of basic research, believing that work of this sort was most likely to lead to significant breakthroughs. Doing so would be made all the more effective by the creation of a National Science Foundation, which would issue and administer unrestricted grants on behalf of the federal government. It was Pauling’s ultimate vision that the majority of research dollars be provided by the federal government, with supplementary funding being made available by state governments, permanent endowments, private foundations, and industry.

“Chemistry and the world of today.” Chemical and Engineering News, September 1949.

The themes put forth by Pauling in his initial message to the ACS – particularly the need for a National Science Foundation – were continued in his presidential address, delivered in fall 1949.

Pauling opened his talk with a broad question, “What can I say under the title ‘Chemistry and the World of Today?'” His answer was “that I can say anything, discuss any feature of modern life, because every aspect of the world today – even politics and international relations – is affected by chemistry.”

Pauling’s all-roads-lead-to-chemistry perspective informed his strong support of a potential National Science Foundation and his firm belief in the value of basic research. He lamented the ongoing struggle for funding faced by so many of his colleagues, and pressed the notion that even applied science was dependent on advances in basic science. Moreover, Pauling suggested that applied science often received the credit for ideas that had initially been discovered or cultivated by basic researchers.

Above all, Pauling believed that, in the post-war era, “…a nation’s strength will lie largely in the quality of its science and scientists.” That noted, Pauling emphasized that government funding for scientific research should not be funneled toward military channels. To this end, it was the responsibility of the ACS, as an organization representing American chemists, to make its voice heard in the fight for the creation of a National Science Foundation.

During Pauling’s presidential year, the concept of the NSF had been put forth in political circles but had not yet been acted upon. Looking forward to that day (which would, in fact, come the next year) Pauling put forth an ideal scenario where the NSF would fund $250 million a year in research, while science-dependent industries would fund an additional $75 million. Of this latter contribution, Pauling believed that private funding ought to be considered as a form of insurance rather than charity, since it was certain to fuel the scientific discoveries necessary to drive industrial development.

“Structural chemistry in relation to biology and medicine.” Second Bicentennial Science Lecture of the City College Chemistry Alumni Association, New York, December 7, 1949. Baskerville Chemical Journal, February 1950.

At the end of 1949, Pauling gave another high profile public lecture, this time to the City College Chemistry Association in New York. In this talk, he focused on the relationships between structural chemistry, biochemistry, and molecular medicine.

Pauling began by citing the role that chemistry had played in catalyzing immense achievement in medicine over the preceding half-century, referencing in particular the discovery and refinement of chemotherapeutic agents including antibiotics. That said, Pauling was quick to point out that scientists still had a very poor understanding of the principles and structural attributes underlying chemotherapeutic functions. It was Pauling’s belief that “…if a detailed understanding of the molecular basis of chemotherapeutic activity were to be obtained, the advance of medicine would be greatly accelerated,” and that structural chemistry was fast approaching a point where it could produce this understanding. Once done, Pauling suggested that the decade or two that followed would surely offer significant advancements in the scientific understanding of medicine and the development of new pharmaceuticals.

Pauling then identified a collection of major areas where he thought biomedical research should be focused. The first involved developing a detailed molecular structure of 1) chemotherapeutic substances (i.e., antibiotics and other medications), 2) the organisms against which they are directed (bacteria, viruses, etc.), and 3) the human organism which they are meant to protect. A second major program of work should delve into the nature of the forces involved in the intermolecular interactions between the above substances and organisms.

Pauling pointed out that the last quarter century had seen great progress in the first goal – the science of organic chemistry had been developed and the structures of many organic compounds had been confirmed. But progress elsewhere, though promising, had not come about so quickly. For questions related to the physiology of disease-causing organisms and of the human body itself, advancements were fated to be slow simply due to the immensity of the task. In addition, structural chemistry was a fairly new field and, although it was growing quickly, the stock of previous discoveries upon which one might expand was finite (research thus far had mainly focused on the structures of amino acids and peptides).

The latter goal, an understanding of the intermolecular interactions between chemotherapeutic substances and the organisms they are meant to treat or defeat, had seen the least progress of all. It was a complicated task for sure, and though he had very little data in hand, Pauling offered a back of the envelope theory about what might be going on, speculating that

…some drugs operate by undergoing a chemical reaction with a constituent of the living organism, and that others operate by the formation of complexes involving only forces that are usually called intermolecular forces.

Regardless, Pauling felt that work in these areas would prove integral to the conduct of future medical research, and he put forth his own work on sickle cell anemia as an example of how other investigations might unfold. Specifically, Pauling and his team had discovered that the hemoglobin present in the red blood cells of afflicted individuals differed structurally from normal hemoglobin. Were other investigators able to develop a similar molecular understanding of a given disease, producing new treatments would be that much easier, since chemotherapeutic agents could be tailored to fit a particular molecular architecture. Work of this sort would

…represent the first time that a chemotherapeutic agent had been developed purely through the application of logical scientific argument, without the significant interference of the element of chance.

Similar to his call for an NSF, Pauling encouraged the creation of an institute for medical chemistry that would train a new generation of students to apply chemistry to medical problems. Doing so, in Pauling’s view, ought to be prioritized due to its potential significance to the health and happiness of all people.