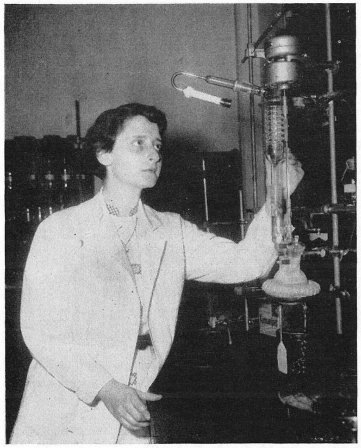

Dorothy Semenow

Dorothy Semenow[Pauling as Administrator]

As the 1950s moved forward, Linus Pauling’s increasingly public stances on nuclear weapons and peace issues emerged as a public relations problem for the California Institute of Technology’s administration, as they repeatedly were forced to respond to charges that Pauling was a communist. As this problem became more pronounced, three of the Institute’s trustees made good on threats to resign because of Pauling’s public image.

That image also drew the attention of fellow scientists around the country. In one instance, W. H. Eberhardt of the Georgia Institute of Technology asked Pauling about Louis Budenz, a former Communist Party member turned informant, who had testified before a government panel in early 1953 that Pauling was a “member of the Communist Party under discipline.” In his reply, Pauling explained that the accusation meant that there was no actual evidence that showed that Pauling was a member of the Communist Party. Pauling added that he was “pretty irritated” by Budenz’ testimony, but as Chairman of the Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Pauling was obliged to set his irritations aside as he dealt with a wide array of professional responsibilities.

As a division chair at Caltech, Pauling was, by default, forced to deny entry to any women applicants who wished to pursue graduate study within the unit. Caltech’s formal policy was that women not be admitted at any level, though they could be employed as post-doctoral research assistants.

In practice, even a post-doctoral appointment rarely happened. One potential post-doc, I. E. Keszler, was considered in the spring of 1953, but ultimately turned away by Lazlo Zechmeister because her interest in developing tests to determine the dyes used in wines was considered to be too tangential a research question. Women seeking to become graduate students did not, of course, receive even that level of consideration, but that would change the same year that Keszler was denied.

The woman who broke through Caltech’s glass ceiling was Dorothy Semenow, a graduate student in chemistry working with John D. Roberts at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. When Roberts accepted a position at Caltech, Semenow expressed a desire to relocate as well, so that she could continue working with him. After receiving an “informal application” from Semenow in February, Pauling brought her case to William N. Lacey, Caltech’s Dean of Graduate Studies. Lacey replied that he would have to take this situation to the Graduate Committee, who would then need to make a recommendation to the Faculty Board and also gain the approval of the Board of Trustees.

The following week, the division faculty deliberated on the language of a request that would be made to the Faculty Board asking that the Committee on Graduate Study be empowered to admit women as graduate students. The guidance emphasized in the request, which would be echoed as the process moved along, was that women would only be admitted

when, in the opinion of the sponsoring Division and of the Committee on Graduate Study, the applicant possesses exceptional qualifications for admission to graduate study and gives unusual promise of continuing scientific productivity.

Since the Committee on Graduate Study would be deciding on individual cases, Pauling requested that they also provide their opinion to the Faculty Board. Carl Niemann seconded Pauling’s request and it was passed without dissent, though some abstained. A month later, Pauling forwarded the division’s recommendation to the Faculty Board who quickly approved it. It would take until the end of spring for the Board of Trustees to also agree to admit women as graduate students.

Semenow’s next hurdle was for the faculty of the Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering to vote to admit her as a Ph.D. student. She cleared this hurdle by a vote of 17 to 3 in favor, with Donald Yost, Dan Campbell, and J. Holmes Sturdivant voting against. William Corcoran and B. H. Sage voted in the affirmative, but with the stipulation that Semenow be permitted entry as long as doing so not prevent a comparable male applicant from being admitted. An additional faculty member, William Lacey, voted in favor with the caveat that he was generally against the admission of women to Caltech, but thought that “since the Faculty voted to permit it, I believe that Miss Semenow’s case is a suitable one to try out on the Committee of Graduate Study.”

To get the Committee on Graduate Studies to approve Semenow, the division next had to prove that she was a promising student. Carl Niemann was asked to assist with this process and, in due course, met with Mary Sherrill, chair of Chemistry at Semenow’s undergraduate alma mater, Mount Holyoke College. Following this conversation, Niemann reported to Dean Lacey that “Miss Semenow has a genuine interest in chemistry as a profession and has every intent to continue in this field after receiving her Ph.D. degree.” This affirmation was enough to secure Semenow’s spot at Caltech.

With Semenow’s case decided, the Institute felt more free to admit other women as graduate students. In April 1954, the Committee on Graduate Study recommended that Estelle Maxine Fowler be admitted as a Ph.D. student in mathematics, and the following spring they approved Elizabeth K. Rosenthal for graduate study in biochemistry and Caroline S. Teichemann in aeronautics. It would take more than two decades for Caltech to take similar action on the undergraduate level — not until 1973 did a woman receive a bachelor’s degree from the Institute.

In 1955, just two years after being accepted, Dorothy Semenow completed her Ph.D. in chemistry and biology, becoming the first woman at Caltech to do so. Following that, Semenow opted to remain in Pasadena and attempted to continue her research without access to laboratory space.

As it turned out, this caused problems. In July 1957, Carl Niemann, writing as acting division chair, informed Semenow that she had been seen entering the division’s laboratories twice after hours with a key. Niemann asked Semenow to return her key and warned her that she could be arrested if she was caught again without the accompaniment of an authorized staff member. She was also warned that she was not to use the laboratory facilities under any conditions. Thus admonished, Semenow continued to push forward her research while staying out of trouble with the division.

In the years that followed, Semenow went on to earn another Ph.D., this one in psychology. She also continued to pursue chemical research, focusing on the molecular components of potential neurotransmitters of acetylcholine and norepinephrine, and often colloborating with her spouse, Donald Garwood, whom she met while at Caltech.

The couple reached out to Pauling in 1968 in hopes that he might help them to secure a research position at the University of California – San Diego, where he was working at the time. After looking over their research statements, Pauling’s colleague Robert Livingston judged that Semenow and Garwood’s work did not overlap sufficiently with the interests of UCSD’s Neuroscience department, and so ended the inquiry. This appears to have been Linus Pauling’s last major interaction with Dorothy Semenow, a pioneering figure in the history of the California Institute of Technology.