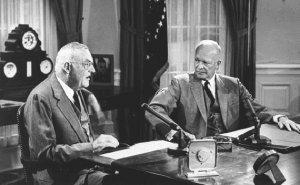

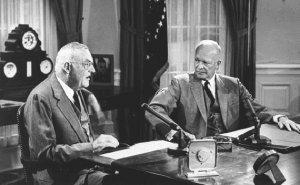

- U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles (left) and President Eisenhower (right)

The following is a research sample of a chapter on the American Empire in the Middle East in The People’s Book Project. This chapter was made possible through donations from readers like you through The People’s Grants. The new objective of The People’s Grants is to raise $1,600 to finance the development of two chapters on a radical history of race and poverty. If you find the following research informative, please consider donating to support The People’s Book Project.

The following sample is a compilation of unedited research, largely drawn from official government documents of the State Department, CIA, Pentagon, White House, and National Security Council, outlining the development of the Eisenhower Doctrine and the American imperial perceptions of the threat of ‘Arab Nationalism.’

The Eisenhower Doctrine and the Threat of Arab Nationalism

Following the Suez Crisis, Nasser’s influence and reputation was enormously strengthened in the Arab, Muslim, and wider decolonizing world, while those of Britain and France were in decline. Nasser’s support for nationalist movements in North Africa, particular Algeria, increasingly became cause for concern. Pro-Western governments in the Middle East stood on unstable ground, threatened by the ever-expanding wave of Pan-Arab nationalism and indeed, Pan-African nationalism spreading from North Africa downward. The United States, however, noting the power vacuum created by the defeat of Britain and France in the conflict, as well as the increasing support from the Soviet Union for nationalist movements in the region as elsewhere, had to decide upon a more direct strategy for maintaining dominance in the region.

As President Eisenhower stated in December of 1956, as the Suez Crisis was coming to a final close, “We have no intention of standing idly by… to see the southern flank of NATO completely collapse through Communist penetration and success in the Mid East.” Secretary Dulles stated in turn, that, “we intend to make our presence more strongly felt in the Middle East.” Thus, the Eisenhower Doctrine was approved in early 1957, calling for the dispersal of “$200 million in economic and military aid and to commit armed forces to defend any country seeking assistance against international communism,” explaining that, “the existing vacuum… must be filled by the United States before it is filled by Russia.” Thus, Eisenhower told Congress, this new doctrine was “important… to the peace of the world.” Some Senators opposed the doctrine; though, with powerful political figures supporting it, as well as the New York Times providing an unfailing endorsement, it was approved in early March of 1957. In the Middle East, Libya, Lebanon, Turkey, Iran, and Pakistan endorsed the doctrine in the hopes of receiving economic and military aid (even before the U.S. Congress approved it), King Hussein of Jordan endorsed it, and funds were further given to Iraq and Saudi Arabia.[1]

The main opposition to the Eisenhower Doctrine came from Syria and Egypt. Nasser later reflected that the doctrine appeared to be “a device to re-establish imperial control by non-military means,” and therefore he would “have nothing to do with it and felt it was directed at Egypt as much as at any communist threat.”[2] This was not, as it turned out, far from the truth. A State Department Policy Planning Paper from early December of 1956 discussed the formation of a new regional policy (which resulted in the Eisenhower Doctrine), and while focusing on the notion that, “[t]he primary threat to the interests of the United States and the West in the Middle East (especially oil, Suez Canal and pipelines) arises from Soviet efforts at penetration,” Nasser and Egypt figured prominently in this formulation, but couched in the rhetoric of the Cold War. In fact, “Soviet penetration” of the Middle East was stated to rest on three main factors, the first of which was identified as the “ambitions of Nasser and the willingness of Nasser and the Syrians to work with the Soviets, especially to obtain arms.” The other two main factors were identified as, “instability and divisions among the other Middle Eastern nations,” referring to Western puppet governments in the region, and “increased animosity toward the UK and France resulting from their military action against Egypt and intensified by the fact that their action was taken in conjunction with Israel’s invasion of Egypt.”[3]

Thus, while the strategy was presented as a means to prevent Soviet “penetration” of the Middle East, the actual content and objectives of the strategy being formulated were directly related to checking Egyptian influence in the region and beyond. Of course, Soviet advances in the area were of concern to the Americans, that cannot be denied, but the prevalence of Egypt and Nasserist influence as a decisive “Third Force” was undeniable as a source of fear among imperial strategists. The strategy overtly stated that “efforts to counter Soviet penetration” in the region “must include measures to… [c]ircumscribe Nasser’s power and influence.” Noting that the American stance during the Suez Crisis has “greatly increased our prestige and opportunity for leadership,” in presenting the view that the United States is “firmly committed to support[ing] genuine independence for the countries concerned,” the State Department document noted that the U.S. would have to avoid “counter suspicion that our aim is to dominate or control any of the countries or to reimpose British domination in a different form. For this reason, our actions will be largely self-defeating if they create a general impression that our objective is directly to overthrow Nasser.” That of course, implies that it is the “indirect objective” of the policy to overthrow Nasser. Noting that Egypt would likely oppose all the measures put forward by the United States in its regional policy, the Policy Planning Paper stated that, “We should play upon [Nasser’s] opposition to stigmatize Egypt as an impediment to peace and progress in the Middle East,” of which the objective would be “to mobilize opinion against Nasser and to circumscribe his power and influence.” The paper stated that it would be important to inform the U.K. and France that the U.S. objective of the program “is directed toward countering Soviet penetration in the Middle East and circumscribing Nasser’s power and influence,” and thus, it would “serve their interests as well as ours,” having in mind “the vital importance of the Middle East to Western Europe.” As such, the U.K. and France should be convinced to “avoid injecting themselves in the Middle East and leave to the US the primary responsibility of restoring the Western position in the area.”[4]

A National Security Council (NSC) report explained that the “opportunistic and nationalistic Nasser government of Egypt gained in influence throughout the area and other Arab heads of state were less able to resist the formation of governments which catered to this surge of nationalism.” Syria was an obvious example; however, even Western friendly governments had to submit to various nationalistic pressures, as Jordan abrogated the Anglo-Jordanian Treaty with Britain, and “King Saud, while publicly friendly to Nasser and the Arab cause, maintained an independent position using his influence for moderation on nationalistic elements, steering a course between the extreme pro-Soviet and strongly pro-West Arab groups.” It’s important to note how Arab nationalism is described as “the extreme pro-Soviet” course when it actually represented a “Third Force” not allied to either the West or East. While the U.S. had an “extremely favorable” position in the Middle East following the Suez Crisis, the USSR was subsequently “given the greatest credit in the Arab world for the cessation of hostilities in Egypt.” Egypt and Syria increased their economic and military ties with the Soviet bloc, and through such support to these and other Arab nations, “the Soviet Union appeared as the defender of the sovereignty of small countries and of Arab nationalism against the threats of Western ‘imperialism’.”[5] Explaining the “major operating problems” facing the United States in the region, nationalism was identified as the primary threat. The NSC Operations Coordinating Board report stated:

Throughout the Arab area there have been increasing manifestations of an awakened nationalism, springing in part from a desire to end both real and imagined vestiges of the mandate and colonial periods, but stimulated by opportunism, Soviet propaganda, aid and infiltration, and by Egyptian ambitions and intrigue. Because the former mandatory and colonial powers were from Western Europe, the nationalism has assumed generally an anti-Western form. This situation has created opportunities for Soviet exploitation, and has, at the same time, placed the United States in a difficult position. The natural U.S. sympathy with those genuinely desirous of becoming free and completely sovereign nations runs, at times, into sharp conflict with actions required to maintain the strength of the Western alliance and to support our closest allies.[6]

Further problems include the threat to Western economic interests in the area, with the potential for nationalization following the example of the Suez Canal, which could put at risk substantial U.S. private investments in the Arab world. Another major problem was with the divides within the Western alliance itself on how it viewed the Arab world and its problems. Significantly, “the United States sees in nationalism much that represents a threat to the West,” but “it tends to regard this nationalism as an inevitable development which should be channeled, not opposed,” whereas “Britain and France have seen this nationalism… as a threat to their entire position in the area.” The NSC paper lamented that, “It is likely that for the time being Nasser will remain the leader in Egypt,” but “the United States cannot successfully deal with President Nasser.” The United States, then, must determine “the degree to which it will actively seek to curb Nasser’s influence and Egyptian activities in the Near East and Africa.”[7]

Syria became an important part of this equation. Increasingly left-leaning, with major pipelines carrying oil to the Mediterranean supplying much-needed oil for Western Europe’s recovery, and the largest Communist Party in the Arab world, Syria was a strategic nightmare for Western interests. After the Suez Crisis, Syria and Egypt both edged toward closer ties with the Soviet Union, not out of an ideological proclivity toward communism, but because of a pragmatic approach toward preserving and expanding Arab nationalism, which the West was actively opposed to while the USSR had endorsed, naturally, as a means to gaining strategic inroads into the Middle East, not out of any benevolent conception of justice for colonized peoples. In 1956, President Eisenhower stated:

Syria was far more vulnerable to Communist penetration than was Egypt. In Egypt, where one strong man prevailed, Colonel Nasser was able to deal with Communists and accept their aid with some degree of safety simply because he demanded that all Soviet operations be conducted through himself. In Syria, where a weak man was in charge of the government [Quwatli], the Soviet penetration bypassed the government and dealt directly with the various agencies, the army, the foreign ministry, and the political parties. Syria was considered ripe to be plucked at any time.[8]

The fears of Soviet penetration were of course exaggerated beyond the on-the-ground realities, as per usual. The real fear was the potential for Syria to more closely align with Egypt and become a strong partner in Nasser’s non-aligned “Third Force” which happened to be in a location of major strategic interest to the West. As the Eisenhower Doctrine framed the language in terms of the Cold War confrontation between the West and East, the internal documents leading to the formation of the doctrine pointed to the isolation and diminution of Egyptian influence in the region as the main objective. Britain’s only remaining pseudo-protectorate in the region through which it could protect its oil interests was in Iraq, while its relationship with Jordan was faltering under nationalistic pressure. The British then, had a major interest in Syria, a an idea was being pushed through Iraq where the leader of the country, Nuri al-Said, “had sought to take the leadership of the Arab nationalist movement away from Egypt by instituting a ‘Fertile Crescent’ union of Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan.” The British objective and vision for the region, not coincidentally, “corresponded with this ambition.” Syria was viewed as a potential point through which to secure access to oil by ensuring a pro-Iraqi government, as well as checking Arab nationalism and Nasser.[9]

In October of 1957, the United States produced a National Intelligence Estimate analyzing “probable developments affecting US interests” in the Middle East “during the next several years.” The outlook for the United States and the West in the Middle East “has deteriorated,” stated the estimate. The USSR’s influence has increased by “supporting the radical element of the Arab nationalist movement,” meaning Nasser. The NIE stated that, “radical Arab nationalists control only Egypt and Syria” at the moment, however, “sympathy and support for their strong anti-Western, revolutionary, and pan-Arab policies come from a substantial majority of the Arabs of the Near East,” while the indigenous support for the West in the region “comes largely from the outnumbered and often weakly-led conservative nationalist elements.” Acknowledging that the regimes in Syria and Egypt were likely to maintain for a few years, their reliance upon the Soviet Union would likely increase, and, moreover, “Nasser and the Syrian leaders will probably continue to exert a powerful influence over radical Arab nationalists throughout the area, except in the unlikely event of their emerging clearly as Soviet puppets.” Even if these specific regimes collapsed, noted the NIE, “the radical Arab nationalist movement will continue as a basic element in the Near East situation.”[10]

The “conservative grouping” which supports the West in the region, consists of Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Iraq, and Lebanon, “forms a loose coalition of regimes that look to the US for aid because of their common interest in the existing system and opposition to the forces of revolution represented by the radicals.” While they do not oppose Arab nationalism in general, for it also justifies their own self-rule, they remain conservative and opposed to radical elements typified by Nasser. The NIE noted that the potential “for broadening or consolidating the position of the conservative forces in the Arab states are poor, although these forces will continue to be an important factor in the area.” One of the main problems was the continued Arab-Israeli dispute, of which prospects for a solution were poor. The NIE warned that the United States believed “that there will almost certainly be some armed conflict in the area during the next several years,” likely in Syria, Jordan, Yemen, and potentially with Israel. While France and the U.K. have lost influence in the region, the USSR has increased its own, with supplying arms to Egypt, Syria, and Yemen, and the U.S. is the main representative of the West in the Middle East. As such, the NIE stated, the region “has thus become a principal arena of the contest between the US and the USSR.”[11]

Since the Suez Crisis, “Nasser has become… the spokesman and symbol of radical Pan-Arab nationalism.” Yet, the conservative forces in the region, especially Iraq, Lebanon, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia, remained increasingly distrustful of Nasser, and thus welcomed the Eisenhower Doctrine “as an opportunity to strengthen their own positions,” resulting in “a division of the Arab Near East into two loose groupings.” The radical Pan-Arab nationalist movement of Nasser and Syria “advocate the union of all Arabs in a single state,” and are “both the most dynamic and the most violent in their anti-Westernism, the most interested in a military buildup as a symbol of Arab strength, and at the present time the most activist in their hostility toward Israel.” Nasser and the Syrian leaders, stated the NIE, “are revolutionaries who believe in replacing many traditional social and economic institutions with a state socialism of their own devising.” Importantly, the NIE observed that, “[t]he majority of politically conscious Arab Moslems throughout the Near East, particularly the middle class intelligentsia, are sympathetic to this concept of Arab nationalism,” and believe that the interests of the West in the region are “Israel, oil, and domination of the area.” Further, they “also believe the West to be opposed to their concept of Arab unity.” The conservative elements, which reject the radical notions of Arab nationalism, reject ties to the Soviet Union, and draw themselves close to the West, are “largely confined to the upper and professional classes and [have] little popular support.” In other words, the pro-West regimes are simply dominated by “conservative and traditional” elites, while the majority of the population of the region support Nasser’s vision of Pan-Arab nationalism.[12]

Oil interests in the region remained paramount for the West. The NIE took note of the fact that the “non-Communist world looks increasingly for its petroleum requirements to the vast reserves of the Middle East,” which was “particularly true of Western Europe,” which in 1957, “consumes almost three million barrels of oil per day, of which 72 percent comes from the Middle East,” and that rate was expected to increase by 1965. Nationalistic governments and movements in the region were exerting increasing pressure upon the “existing pattern of oil production and transportation” in seeking “increased revenue and more control over oil operations.” Luckily for the West, the conservative elements control the major oil producing areas, but transportation of oil through pipelines and waterways go through areas dominated by the radical Arab nationalist regimes. In fact, 35% of oil going to the West from the region was transported by pipeline, while 65% went through the Suez Canal. The NIE noted, however, that “Egypt and Syria are unlikely, except under extreme provocation, to exercise their capability to stop the flow of oil from the Persian Gulf area to the Mediterranean.” Opposition to Israel was identified as “the principal point of agreement among all factions of Arabs and acute tension between the Arab states and Israel will continue.” The Cold War struggle between the West and East “is regarded as a battle of giants which concerns the Arab world only insofar as it intrudes in Arab affairs or offers opportunities to the Arabs to advance their own interests.” Thus, Arab views toward the Soviet Union and the West are not framed in the Cold War dialectic of the “Free World” versus “Communist dictatorship,” but rather “the result of past experience, present friction, and future aspirations,” which naturally put the West in the part of imperial aggressors, while the Soviet Union can legitimately portray itself as ‘anti-imperial.’ The United States will continue to represent the West in the region, but “Britain, France, and other Western states will be critical of US policy if it does not act effectively to protect Western interests, particularly in petroleum, when threatened.”[13]

Western influence had increased among the conservative Arab regimes over the preceding year, but has failed to be recognized “among the Arab public,” who fail “to understand Western indignation at Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal Company and at his taking Soviet arms.” The French-British-Israeli invasion of Egypt confirmed the radical Arab nationalist portrayal of “Western imperialists,” and, while U.S. actions during the crisis increased its favor in the region, the “Soviet threats against the UK made an equal or greater impression on the Arab public.” The U.S. stance during the crisis “was misinterpreted among the Arabs as an indication that the US intended to back the Pan-Arab program against the UK and France, and many became confused and disillusioned when this turned out not to be the case.” While radical Arab nationalism will continue over the following years, stated the NIE, “[t]he forces of conservative Arab nationalism are likely to continue to be generally identified with the West,” and in some areas this could lead to “instability.” Israel, for its part, “will continue to receive outside financial and diplomatic support [largely from France] and will persist as a dynamic force within the area,” as well as seeking “to keep its armed forces qualitatively superior to those of its Arab opponents.”[14]

For Western interests in the region, a number of factors had to dictate American policy. Naturally, the possibility of cooperation with Syria and Egypt remained slim, while conservative Arab governments were “likely to become progressively more dependent upon the US,” which would mean that “economic progress in these states will be regarded in the area as an index of the value of association with the US.” The increasing “public expectation of improvement in economic standards and welfare will impose difficulties upon governments,” as the “radical nationalist governments of Egypt and Syria are committed to ambitious social and economic reforms,” though they may likely fail to “fulfill their expectations, even with Soviet assistance, and they will probably experience political difficulties as a consequence.” For the conservative governments, which are home to the vast oil reserves of the region, they will have the “financial resources with which to effect reforms which would probably broaden the base of popular support and thus ultimately strengthen their position and that of the conservative grouping.”[15]

Syria and Jordan: The Evolution of a Crisis

The Syrian Crisis emerged between July and October of 1957, after the Ba’ath Party (an Arab Socialist party) won control of the Parliament and Cabinet in early January, with increased Syrian disputes with Turkey over territory, reluctance to grant the Saudi ARAMCO company a pipeline across the country (owned by the Rockefeller Standard Oil Company), and the acceptance of left-wing Arab groups, the “moderate” Syrian leadership was increasingly sidelined. The United States and its Western allies, particularly Britain, had been involved for a number of years in supporting various coups in Syria. One coup was supposed to take place in 1956, but was outflanked by the importance of the Suez Crisis. Codenamed Operation Straggle, it was felt that the plans could be resumed once the British and French had left Suez. Thus, in late 1956, the British and Americans began again discussing “certain operational intentions regarding Syria,” and the CIA stated that “the UK, France, Turkey, Israel, and Iraq all… would welcome US participation and support in strong measures to check or counter the leftward trends in Syria.” With the passing of the Eisenhower Doctrine, Syria had been identified “as evidence of Russian intent” in the region. Syria, of course, denounced the doctrine, and American strategists, such as Allen Dulles at the CIA, increasingly painted Syria with a Soviet brush.[16]

Jordan played an increasingly important role in this situation. King Abdullah, long supported and in fact, put in power by the British, had been assassinated by a Palestinian in 1951. In 1953, King Hussein emerged as the conservative leader of the country. Jordan, situated between Israel, Syria, and Saudi Arabia, was a pivotal player in any schemes at regional “stability” and preventing the spread of Pan-Arab nationalism. As Britain’s influence in the region dissipated, King Hussein sought to cement his regime’s ties with the Americans. Jordan had, for years, been subjected to cross-border raids from Israeli commandos, and the conservative pro-Western government of Jordan had to subdue national public opinion to refrain from striking back. The U.S. attempted to pressure Jordan into a peace settlement with Israel, but when Colonel Ariel Sharon destroyed a West Bank village in 1953, killing sixty-nine Palestinians, most of whom were women and children, “such a hope [had] been dashed to smithereens,” said a U.S. official at the time. Jordan had to wrestle with the reality of being home to a massive Palestinian refugee population, which was the source of enormous instability and caution for any regime in power. While King Hussein, due largely to domestic pressures, refrained from joining the Baghdad Pact (an alliance between Britain, Iraq, and Turkey), once Nasser had purchased Soviet arms in 1955, both the UK and United States began to see Hussein’s Jordan as “virtually impotent” in the confrontation of “universal popular Jordanian enthusiasm for [the] flame of Arab political liberation ignited by Nasser’s arms deal.” Thus, reported an American official in Amman, the capitol of Jordan, the “[p]olitical situation in Jordan is disintegrating and resulting instability is playing into [the] hands of anti-Western nationalists and Communists.”[17]

The British, in response, attempted to entice Jordan to join the Baghdad Pact, which was looked favourably upon by King Hussein. However, when news of this spread to the West Bank, wrote Douglas Little, “anti-Western demonstrations erupted and pro-Nasser Palestinians demanded that Hussein sever his ties with Britain and rely instead on Soviet arms and Saudi gold.” Thus, lamented a British official, “If Saudi/Egyptian/Communist intrigue can prevent Jordan joining the Pact… despite the King and Government wishing to do so… how far has the rot spread?” The “rot” referred to by the British official, of course, was Arab nationalism. Many American officials felt that Britain would be completely extricated from Jordan, leaving CIA Director Allen Dulles to comment in early 1956 that, “The British… have suffered their most humiliating defeat in modern history.” King Hussein shortly thereafter removed the head of the Arab Legion, which was the British-controlled Jordanian army, and put the army under absolute Jordanian control, leading the British to cut Jordanian economic and military aid in retribution. The Americans, however, felt this was a smart move by Hussein, as the “King is now [a] hero and no longer [a] puppet.” Hussein put in place a new leader of the Arab Legion, described by some as an “anti-Western opportunist,” of whom the British presented as having an objective for Jordan that, “is likely to be a military dictatorship on the lines of Colonel Nasser.” This leader, Abu Nuwar, even invoked many concerns among the Americans, who were wary of his pro-Nasser stance and his ties to Palestinian leaders in the West Bank. With the Suez Crisis under way, Jordan requested Iraq send hundreds of military advisers, to which Israel responded with “savage blows” against the Arab Legion, in Eisenhower’s own words, increasing the fear that, “Jordan is going to break up… like the partition of Poland.”[18]

In October of 1956, elections in Jordan led to the formation of a Government coalition of Communists and anti-Western nationalists, “led by Sulieman Nabulsi, a pro-Palestinian East Bank activist whom [King] Hussein reluctantly named prime minister on the eve of the Suez war.” As British participation in the Suez war became clear, Jordan’s government threatened to toss out the Anglo-Jordanian Treaty of 1948, leading Arab Legion chief Abu Nuwar to warn U.S. diplomats that, “If [the] US wants to salvage anything in Jordan,” it would have to act quickly to “furnish military and economic aid… [to] compensate for British aid which will soon be ended.” Hussein warned the Americans that Nuwar and Nabulsi were even considering Soviet aid as a replacement for British subsidy. Thus, the United States jumped into Jordan with $30 million in aid. With the Eisenhower Doctrine unveiled in early 1957, Hussein quietly endorsed the program, to which he was rewarded with suitcases of cash from the CIA, and in April, Hussein forced the prime minister to resign, instigating large anti-Western protests. At that time, however, Allen Dulles informed the National Security Council, “The situation in Jordan had reached the ultimate anticipated crisis… The real power of decision rests largely with the Army, whose loyalty to the King is uncertain.” Two days later, amid protests denouncing the Baghdad Pact and the Eisenhower Doctrine, Nuwar, the head of the Army, attempted to oust King Hussein in a coup. The King, however, was not taken by surprise. With the help of the CIA’s Kermit Roosevelt, he had mobilized loyalist army factions who forced Nuwar into exile in Syria. The crisis, however, continued, as massive anti-US demonstrations took place in Amman and Jerusalem, leading Hussein to ask Secretary of State John Foster Dulles if he could count on US support in proposing “to take a strong line in Jordan, including martial law on the West Bank.” Dulles then urged Eisenhower to send a battalion of US Marines into the Eastern Mediterranean “to signal US support for the embattled Hussein.”[19]

The United States then immediately granted $10 million in economic aid to Jordan, followed closely with $10 million in military aid, both provided through the auspices of the Eisenhower Doctrine, designed to ensure that the Arab Legion remained as “as effective force for the maintenance of internal security,” which translates into domestic repression. Jordan got a new Prime Minister, ostensibly pro-Western, and America increasingly replaced the British as the imperial master of Jordan. Problems persisted, however, as Secretary Dulles noted, as within “wretchedly poor” Jordan, the Palestinians “were a continuing menace to stability,” and “the King sat on dynamite where the refugees were concerned.”[20]

The Syrian Crisis

At the same time, as the crisis began to boil over in Syria, Eisenhower stated that, “If by some miracle stability could also be achieved in Syria,” by which he means pro-Western subservience, “American would have come a long way in an effort to establish peace in that troubled area,” by which he means domination. The CIA, for its part, was already encouraging right-wing factions of the Syrian military to “join forces effectively against the leftists.” In May of 1957, the CIA was attempting to remove “the pro-Communist neutralists” and “achieve a political change in Syria.” With Syrian elections, both Communists and Ba’athist made large gains, while an oil refinery was being constructed at Homs by Czech engineers from the Soviet bloc, and Soviet military advisers made inroads into the nation, resulting in a $500 million grain-for-weapons deal signed with Soviet Premier Khrushchev in July of 1957. In August, the National Security Council’s Operations Coordinating Board produced a report explaining that, “Syrian leaders seem more inclined to accept Soviet influence blindly than in any other country in the area… There was evidence that the Soviets are making Syria the focal point for arms distribution and other activities, in place of Egypt.” Within two days, the United States gave authorization for the covert operation against Syria, which the CIA had been planning for months, aiming to install the former Syrian pro-West leader, Shishakli. This operation, however, according to the U.S. Ambassador to Syria in 1957, was “a particularly clumsy CIA plot” which had been “penetrated by Syrian intelligence.” It was later revealed that, “[h]alf a dozen Syrian officers approached by American officials immediately reported back to the authorities so that the plot was doomed from the start.” Therefore, on August 12, the head of Syrian counterintelligence expelled known CIA agents, arrested their local assets, and put the U.S. Embassy under surveillance. Eisenhower expelled the Syrian ambassador to the United States, which was reciprocated with Syria expelling the American ambassador. Painting the picture of a Syria which was about to “fall under the control of International Communism and become a Soviet satellite,” Secretary Dulles supported invoking the Eisenhower Doctrine.[21]

On August 21, 1957, an emergency meeting on Syria was held at the White House, and Secretary Dulles asked the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to attend, stating that, “We are thinking of the possibility of fairly drastic action… so come with anybody he needs in that respect.” Though the actual minutes of the meeting remain classified, Eisenhower’s memoirs reflect on some of the discussion that took place: “Syria’s neighbors, including her fellow Arab nations, had come to the conclusion that the present regime in Syria had to go; otherwise the takeover by the Communists would soon be complete.” The U.S. would then encourage Iraq and Turkey to mass troops along their borders with Syria, and “if Syrian aggression should provoke a military reaction” – note how it’s defined as “Syrian aggression” as opposed to “reaction” or “defense” to an aggressive military buildup on its borders – the United States would “expedite shipments of arms already committed to the Middle Eastern countries and, further, would replace losses as quickly as possible.” As such, the U.S. Sixth Fleet was again ordered to the eastern shores of the Mediterranean, as it was during the Jordanian crisis earlier that year, while U.S. jets were sent from Western Europe to a NATO base in Turkey. Over the following two weeks, the Americans slowly backed down from their aggressive strategy, which threatened to provoke a major regional war drawing both the Soviet Union and the United States directly into the conflict. Soviet leader Khrushchev wrote a letter to Eisenhower in early September warning him not to intervene in Syria. John Foster Dulles claimed that the crisis had created “a period of the greatest peril for us since the Korean War,” saying that Khrushchev was “more like Hitler than any other Russian leader we have previously seen.” In typical Orwellian fashion, changing the actual crisis from that of a major covert and potentially overt American aggression in the region, Dulles, when speaking to the press, expressed his “deep concern at the apparently growing Soviet Communist domination of Syria.”[22]

While the conservative Arab allies were hesitant to pursue aggressive American policies against Syria, Turkey seemed to be ready for war, as even “despite words of caution from American diplomats and NATO officials,” Turkey “refused to demobilize the 50,000 troops they had massed along the Syrian frontier.” Dulles attempted to placate the Soviets, explaining that Eisenhower was convincing the Turks to retract, and Khrushchev warned, “if Turkey starts hostilities against Syria, this can lead to very grave consequences, and for Turkey, too,” which was a NATO ally, and thus, if Turkey was “to go it alone in Syria,” the Soviet Union would “attack Turkey, thereby precipitating an open, full scale conflict between ourselves and Russia.” With this in mind, U.S. officials bribed Turkey with economic and military aid to demobilize the border in late October. Following the crisis, Syrian leaders saw a dual threat of either Soviet domination of their country or Turkish invasion. In response to this, they promoted a formal union with Egypt along the lines espoused by Pan-Arab nationalism, and in early 1958, the United Arab Republic (UAR) was formed between Syria and Egypt. The Americans then feared that Nasser would use the UAR “to threaten Lebanon, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and Iraq and perhaps engulf them one by one.”[23] However, despite the American fears that the UAR would seek to absorb other Arab states, the United States felt that a merger with Egypt would repress Communist elements in Syria, and that open hostility to the UAR would only incur Arab resentment. Thus, while the UAR was formed on 1 February 1958, the United States formally recognized it on 25 February, and the Syrian crisis came to an end.[24]

U.S. Policy After the Syrian Crisis

On 24 January 1958, a National Security Council report on “Long-Range U.S. Policy Toward the Near East” was issued which explained that the Middle East was “of great strategic, political, and economic importance to the Free World,” as the region “contains the greatest petroleum resources in the world and essential facilities for the transit of military forces and Free World commerce.” Thus, it was deemed that the “security interests of the United States would be critically endangered if the Near East should fall under Soviet influence of control,” and that the “strategic resources are of such importance” to the West, “that it is in the security interest of the United States to make every effort to insure that these resources will be available and will be used for strengthening the Free World,” noting also that the “geographical position of the Near East makes the area a stepping-stone toward the strategic resources of Africa.”[25] The Report went on note:

Current conditions and political trends in the Near East are inimical to Western interests. In the eyes of the majority of Arabs the United States appears to be opposed to the realization of the goals of Arab nationalism. They believe that the United States is seeking to protect its interest in Near East oil by supporting the status quo and opposing political or economic progress, and that the United States is intent upon maneuvering the Arab states into a position in which they will be committed to fight in a World War against the Soviet Union. The USSR, on the other hand, had managed successfully to represent itself to most Arabs as favoring the realization of the goals of Arab nationalism and as being willing to support the Arabs in their efforts to attain those goals without a quid pro quo. Largely as a result of these comparative positions, the prestige of the United States and of the West has declined in the Near East while Soviet influence has greatly increased. The principal points of difficulty which the USSR most successfully exploits are: the Arab-Israeli dispute; Arab aspirations for self-determination and unity; widespread belief that the United States desires to keep the Arab world disunited and is committed to work with “reactionary” [i.e., dictatorial] elements to that end; the Arab attitude toward the East-West struggle; U.S. support of its Western “colonial” allies [France and Britain]; and problems of trade and economic development.[26]

These points of “exploit” are, further, accurate. The United States, affirmed the NSC report, “supports the continued existence of Israel,” and “our economic and cultural interests in the area have led not unnaturally to close U.S. relations with elements in the Arab world whose primary interest lies in the maintenance of relations with the West and the status quo in their countries – Chamoun of Lebanon, King Saud, Nuri of Iraq, King Hussein [of Jordan].” These relations, stated the document, “have contributed to a widespread belief in the area that the United States desires to keep the Arab world disunited and is committed to work with ‘reactionary’ elements to that end,” while the USSR can proclaim “all-out support for Arab unity and for the most extreme Arab nationalist aspirations, because it has no stake in the economic, or political status quo in the area.” In its look at the advances of Communism in the region, the report stated that, “Communist police-state methods seem no worse than similar methods employed by Near East regimes, including some of those supported by the United States,” while the “Arabs sincerely believe that Israel poses a greater threat to their interests than does international Communism.” Lamenting against perceptions of the West in the region, the NSC document noted that the Arabs “believe that our concern over Near East petroleum as essential to the Western alliance, our desires to create indigenous strength [i.e., police-states, dictatorships, strong militaries] to resist Communist subversion or domination, our efforts to maintain existing military transit and base rights and deny them to the USSR, are a mere cover for a desire to divide and dominate the area.”[27]

Unfortunately for the United States reputation, the NSC report stated, “[t]he continuing and necessary association of the United States in the Western European Alliance makes it impossible for us to avoid some identification with the powers which formerly had, and still have, ‘colonial’ interests in the area.” In other words, yes, the United States supports colonialism and imperialism in the Middle East. Further, “[t]he continuing conflict in Algeria excites the Arab world and there is no single Arab leader, no matter how pro-Western he may be on other issues, who is prepared to accept anything short of full Algerian independence as a solution to this problem,” and thus, this creates “fertile ground for Soviet and Arab nationalist distortion of the degree of U.S. and NATO moral and material support to the French in Algeria.” While the area is rife with “extremes of wealth and poverty,” the blame is put on “external factors” such as “colonialism” as well as “unfair arrangements with the oil-producing companies, and a desire on the part of the West to keep the Arab world relatively undeveloped so that it may ultimately become a source of raw materials and the primary market for Israeli industry.” The NSC document then stated that, “we cannot exclude the possibility of having to use force in an attempt to maintain our position in the area,” but that, “we must recognize that the use of military force might not preserve an adequate U.S. political position in the area and might even preserve Western access to Near East oil only with great difficulty.”[28]

As an American objective in the region, the NSC document stated that, “[r]ather than attempting merely to preserve the status quo, [the United States should] seek to guide the revolutionary and nationalistic pressures throughout the area into orderly channels which will not be antagonistic to the West and which will contribute to solving the internal social, political and economic problems of the area.” However, the report went on to essentially counter this point with the policy objective of seeking to “[p]rovide military aid to friendly countries to enhance their internal security and governmental stability,” or in other words, to maintain the status quo, and, “where necessary, to support U.S. plans for the defense of the area.” The document did, however, recommend that when a “pro-Western orientation is unattainable,” to “accept neutralist policies of states in the area even though such states maintain diplomatic, trade and cultural relations with the Soviet bloc… so long as these relations are reasonably balanced by relations with the West.” The United States should “provide assistance… to such states in order to develop local strength against Communist subversion and control and to reduce excessive military and economic dependence on the Soviet bloc.”[29]

In dealing with the “threat” of Pan-Arab nationalism, the NSC report recommended that the United States should proclaim its “support for the ideal of Arab unity,” but to quietly “encourage a strengthening of the ties among Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Iraq with a view to the ultimate federation of two or all of those states.” The aim of this would be to create a “counterbalance [to] Egypt’s preponderant position of leadership in the Arab world by helping increase the political prestige and economic strength of other more moderate Arab states such as Iraq, the Sudan, Saudi Arabia, and Lebanon.” In Syria, the aim was simply to seek “a pro-Western, or if this is not possible, a truly neutral government.” Further, it was essential to continue “friendly relations with King Saud and continue endeavors to persuade him to use his influence for objectives we seek within the Arab world.” Referencing the potential use of covert or overt warfare and regime change, the document stated that the United States had to “[b]e prepared, when required, to come forward, as was done in Iran [with the 1953 coup], with formulas designed to reconcile vital Free World interests in the area’s petroleum resources with the rising tide of nationalism in the area.”[30]

Contribute to The People’s Grant:

Andrew Gavin Marshall is an independent researcher and writer based in Montreal, Canada, writing on a number of social, political, economic, and historical issues. He is also Project Manager of The People’s Book Project. He also hosts a weekly podcast show, “Empire, Power, and People,” on BoilingFrogsPost.com.

Notes

[1] Peter L. Hahn, “Securing the Middle East: The Eisenhower Doctrine of 1957,” Presidential Studies Quarterly, (Vol. 36, No. 1, March 2006), pages 39-40.

[2] Ibid, page 41.

[3] Document 161, “Paper Prepared in the Bureau of Near Eastern, South Asian, and African Affairs and the Policy Planning Staff,” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955-1957, Vol. 12, Near East Region; Iran; Iraq, 5 December 1956.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Document 178, “Operations Coordinating Board Report,” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955-1957, Vol. 12, Near East Region; Iran; Iraq, 22 December 1956.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ivan Pearson, “The Syrian Crisis of 1957, the Anglo-American ‘Special Relationship’, and the 1958 Landings in Jordan and Lebanon,” Middle Eastern Studies (Vol. 43, No. 1, January 2007), pages 45-46.

[9] Ibid, pages 46-47.

[10] Document 266, “National Intelligence Estimate,” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955-1957, Vol. 12, Near East Region; Iran; Iraq, 8 October 1957.

[11 – 15] Ibid.

[16] Douglas Little, “Cold War and Covert Action: The United States and Syria, 1945-1958,” Middle East Journal (Vol. 44, No. 1, Winter 1990), pages 68-69.

[17] Douglas Little, “A Puppet in Search of a Puppeteer? The United States, King Hussein, and Jordan, 1953-1970,” The International History Review (Vol. 17, No. 3, August 1995), pages 512, 516-519.

[18] Ibid, pages 519-522.

[19] Ibid, pages 522-524.

[20] Ibid, pages 524-525.

[21] Douglas Little, “Cold War and Covert Action: The United States and Syria, 1945-1958,” Middle East Journal (Vol. 44, No. 1, Winter 1990), pages 69-71.

[23] Ibid, pages 73-74.

[24] Peter L. Hahn, “Securing the Middle East: The Eisenhower Doctrine of 1957,” Presidential Studies Quarterly, (Vol. 36, No. 1, March 2006), page 44.

[25] Document 5, “National Security Council Report,” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958-1960, Vol. 12, Near East Region; Iraq; Iran; Arabian Peninsula, 24 January 1958.

[26-30] Ibid.

Advertisement