For several richly-deserved reasons, evolutionary psychology has gotten a bad rap. Its sins range from rampant reduction to ridiculous speculation. But not all evolutionary psychology is created equal — there is a softer, subtler, more insightful form that investigates emotions or affects. This form also has the virtue of being grounded in actual neurophysiology rather than imaginary modules. The leading researchers in this field are Jaak Panksepp and Antonio Damasio. I discovered their work just when I was about to write-off evolutionary psychology as a bad blend of mental metaphors, optimal adaptations, and just-so stories. But as Panksepp and Damasio observe, minds are not simply cognitive computing devices flawlessly executing subconscious routines: they are awash in emotions that have evolved over eons for good evolutionary reasons. Cognition, in other words, is comprised not just of thoughts but also of feelings.

In a recent essay (“Animal Spirits”), Stephen Asma describes how his perspective on all this was impacted by a recent trip to ancestral and emotive Africa. Anyone who has spent time in the bush will know — or feel — exactly what he is describing. The realities and atmospherics of life and death in these environments are positively electrifying. But as Asma notes, this is not the kind of electricity that drives computers:

After you spend time with wild animals in the primal [African] ecosystem where our big brains first grew, you have to chuckle a bit at the reigning view of the mind as a computer. Most cognitive scientists, from the logician Alan Turing to the psychologist James Lloyd McClelland, have been narrowly focused on linguistic thought, ignoring the whole embodied organism. They see the mind as a Boolean algebra binary system of 1 or 0, ‘on’ or ‘off’. This has been methodologically useful, and certainly productive for the artifical intelligence we use in our digital technology, but it merely mimics the biological mind. Computer ‘intelligence’ might be impressive, but it is an impersonation of biological intelligence. The ‘wet’ biological mind is embodied in the squishy, organic machinery of our emotional systems — where action-patterns are triggered when chemical cascades cross volumetric tipping points.

Emotions have of course long been used to explain (or partially account for) religious ideas. Freud (and many who uncritically follow him) argued that primal fear generated ideas that eventually came to be characterized as “religious.” But this is too simple. Sensing this, Freud also argued that parental attachment — an evolutionarily ancient trait in mammals, also played a role. While this surely is correct, it still leaves things too simple. As the anthropologist RR Marrett recognized long ago, religious ideas and feelings are always Janus-faced: there is a positive aspect which he called mana, and a negative which he called taboo.

The positive aspects, or affects, were of course the subject of William James’ The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902). Though it remains a classic and something that should be read, I’ve always found it a bit mushy and almost mystical. Even so, James reminds us that religion is never just an idea — it is also an experience that entails the full array of human emotions, including not just fear but also love. More elaborated (or cognitively inflected) emotions, which Damasio characterizes as “feelings,” also have an evolutionary basis — these include awe, curiosity, and wonder. James’ insights have been ably extended, and situated within an embodied-evolutionary framework, by James Fuller. His Spirituality in the Flesh: Bodily Sources of Religious Experience (2008) is a superb collection of essays on these intersections. They remind us that purely cognitive accounts of religion will always fall short, or partially miss the mark.

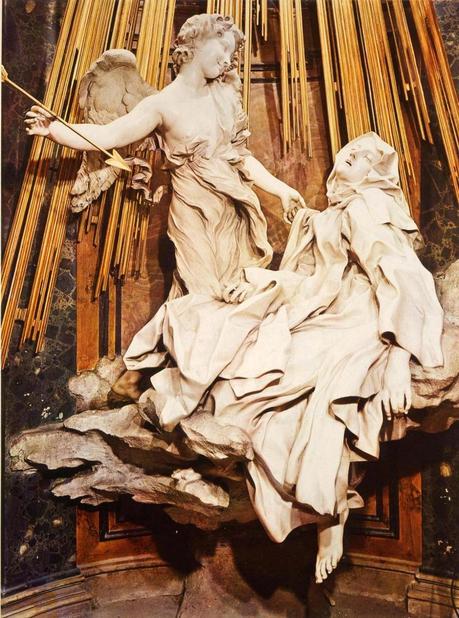

St. Theresa’s Spiritual-Sexual Ecstasy