Much has been made of the revival of ‘90s style – the boxy suits, mallcore tees, and chunky sneakers. If you scroll through the new arrivals section at SSENSE, you’ll find tons of references to that decade’s punk, skate, and even corporate dress culture. The silhouettes are baggy; the clothes hint at teen angst. Even for people who don’t care for most of the clothes, which includes me, it’s hard to deny there’s a bit of sweet sentimentality here that naturally comes with nostalgia. I remember the ‘90s fondly.

The clothes are just superficial, however, covering up what I think is the more defining revival – the sense of irony that was pervasive during the early-aughts. It’s the idea that some things can be so awful, so ugly, and so stupid, they’re ironically considered good. The actual ‘90s wasn’t about irony, it was about apathy, the other defensive mechanism we use to shield ourselves from scrutiny. Irony is about turning something on its head and laughing at it; apathy is about not caring at all. Either way, both are a dissimulation – a way to conceal our true feelings.

Princeton professor Christy Wampole wrote a good opinion piece on this at The New York Times, where she says irony is the ethos of our age, “the primary mode with which daily life is dealt.” However, since this was published years ago, it was more about the middle class, often white, hipster that lives in coastal cities – the kind that yearns for authenticity, but shuns sincerity. Wampole writes that irony is used today as a defensive mechanism to preempt shame, a tool to hide vulnerable emotions:

Take, for example, an ad that calls itself an ad, makes fun of its own format, and attempts to lure its target market to laugh at and with it. It preemptively acknowledges its own failure to accomplish anything meaningful. No attack can be set against it, as it has already conquered itself. The ironic frame functions as a shield against criticism. The same goes for ironic living. Irony is the most self-defensive mode, as it allows a person to dodge responsibility for his or her choices, aesthetic and otherwise. To live ironically is to hide in public.

The perfect example of this is the gag gift, the sort of thing you find in the crowded aisles of a dimly lit Spencer’s Gifts shop. Gag gifts are a way to avoid doing the hard work of actually getting a good present. Finding a personal, meaning gift is stressful; it forces us to look deeply into both ourselves and the other person – as though the first wasn’t hard enough. It can feel intimate and momentous. It sets us up for failure. What if the other person doesn’t like the gift? What if they don’t show us the reaction we hoped for? As Wampole writes, “I somehow cannot bear the thought of a friend disliking a gift I’d chosen with sincerity.”

So, we get the gag gift. A kitschy painting we found in a thrift store; a coffee mug with a corny message; a humorous book that’s not actually meant to be read. You can’t fail with these kinds of gifts because their awfulness is the entire point. At best, you and your friend will share a momentary laugh. At the worst, your friend will politely smile and you can brush it off by saying you never really cared about this in the first place.

This is fashion today – clothes that are so ugly, they’re great; clothes so dumbed down, they show you don’t take yourself too seriously. After almost two decades of relentless editorial coverage on factories and garment construction, it almost feels freeing. Even designers such as Rick Owens and Martin Margiela, known for their very conceptual designs, are rather serious. See Eugene Rabkin’s tisk-tisking what he calls “fashion hipsters” over at The Business of Fashion. Rabkin has always been a joyless critic, but never moreso than when he’s talking about DHL tees and Gosha hoodies.

What we are witnessing is the rise of the fashion hipster — a new consumer class that in its self-image and purchasing habits is not driven by the notion of luxury but by characteristics normally associated with hipsterism — irony, camp, and insider humor. […] The jacket has all the characteristics required for fashion hipster appeal – it is instantly recognizable to the select few through the logo, signaling that you belong to the well-informed in-club at the forefront of fashion, but signaling nothing to the masses. It possesses a sense of irony – it is a security jacket but not. And it has an element of campy humor – it’s so bad that it’s good.

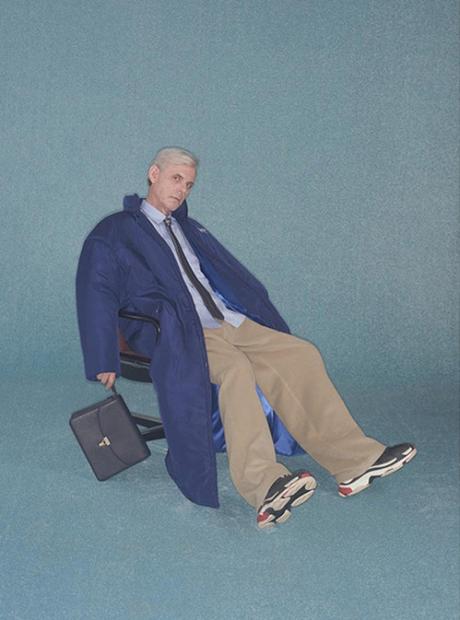

I admit, I own some intentionally ugly clothes. A few months ago, I was telling my friend Pete, who writes at Put This On, about how I own a pair of Raf Simons’ Ozweegos (pictured above). I wear them with black C.O.F. jeans and a matching black Margiela five-zip. The thing about ugly shoes, much like ugly gifts, is that you can’t fail. If you’re honest with yourself, you know when a suit is poorly tailored. If you look ugly in ugly shoes, you’ve somehow gotten it right.

But there comes a point where irony suffocates everything else, making it difficult to be sincere. And the best things in life are sincere – films, art, and even social relationships. In The King’s English, Henry Watson Fowler wrote: “any definition of irony – though hundreds might be given, and very few of them would be accepted – must include this, that the surface meaning and the underlying meaning of what is said are not the same." Sincerity is taking a stand, putting yourself out there, and saying what you think is true (including what you find beautiful). Irony subverts this so people never know what you mean. There’s an element of Vetements that’s poking fun at the fashion industry, but it’s hard to tell who wearing those clothes understands the joke. Demna, in fact, avoids any intellectualizing of his work, almost as though he’s trying to preempt criticism. “Fashion shouldn’t make you dream,” he said. From The Independent:

“Clothes” are exactly what they see fashion as: meaning stuff for people’s backs, as opposed to high-falutin concept garments. “It’s very product-orientated,” says Gvasalia, sounding like anything but an avant-garde fashion designer thought to be at the very cutting-edge. “There are no illusions of, ‘Oh, we want to create a dream about fashion.’ We just want to create clothes that people want to have.

There’s admittedly something oppressive about traditionalism and the avant-garde. They somehow swing too far in the other direction, missing the point that clothes ought to be fun. I don’t mind a bit of campy humor – cheekiness has been the cornerstone of many traditional wardrobes, including prep (see Chipp’s novelty ties). I think the distinction here is less about aesthetics and more about approach.

In her NYT opinion piece, Wampole asks: “where can we find examples of nonironic living? What does it look like?” The answer can be found in those who are very young or very old. A four year-old child will go throughout her day without an ounce of irony. “She likes what she likes and declares it without dissimulation. She is not particularly conscious of the scrutiny of others. She does not hide behind indirect language.” There’s a lot of fashion nowadays that’s continually self-referencing, just layers and layers of meta humor, and encouraging consumers to buy ugly, stupid clothes they’ll dispose of in a year, much like the gag gifts that eventually wind up in landfills. I think it’s OK to love and wear ugly things, so long it’s done earnestly, despite the risks. Ask if something conceals or reveals, if a purchase is something you genuinely love and find meaningful. Ask if this is just an inside joke that’ll get old before you even get to take it home. Ask if you’re feigning indifference only because you care deeply. “The most important question,” writes Wampole. “Ask how would it feel to change yourself quietly, offline, without public display, from within?”