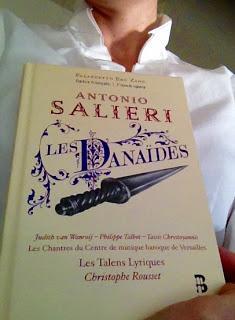

Look at that cover design!

In some corner of my mind, Salieri will always be F. Murray Abraham. I can't help it. To be honest, this was one of the reasons that I jumped at the chance to review a gorgeously-produced recording of his sweeping 1784 opera, Les Danaïdes. Another reason was that it was simply and irresistibly beautiful (see left.) It has the kind of apparatus I can't resist, with critical essays in French and English, lucidly written and in a nice typeface. (I do realize that I'm revealing novel facets and depths of my nerdery, here...) With Les Talens Lyriques led by Christophe Rousset, the musical quality promised to be similarly luxurious, and I was not disappointed. There is an energy and brio to the entire performance that is irresistible. There's also orchestral creativity and moral nuance that I found fascinating. I'm not alone in this. Berlioz, seeing a performance in the 1820s, enthused about the éclat of the drama, the harmonic cooperation of chorus and orchestra, and the talent of the singers. Even without the benefit of dramatic tableaux, it's easy to echo his praise.

In this recording, the opera is given a superb treatment by Les Talens Lyriques. There's a gorgeous tone to the strings throughout, and the ensemble does credit to the score's moments of lightness and celebration as well as to its driven, ominous energy. Throughout, Salieri uses contrast very effectively, alternating rejoicing choruses with tyrannical plotting or duets for Hypermenèstre and Lyncée. The chorus is specialized in baroque music, and it shows: their timing and their diction are alike impeccable. The accomplished soloists also deserve great credit for their attention to text and the emotional urgency with which they invest characters without a high degree of individuality. (I found the opera as a whole engaging and gripping, but the characters are types, if well-developed ones.) Thomas Dolié ably fills secondary roles necessary to the political dimensions of the drama. Judith van Wanroij and Philippe Talbot are the star-crossed lovers Hypermenèstre and Lyncée. Both sang with plangent tone and expressivity throughout. They have a particularly lovely duet, "L'amour à jamais nous enchaine." Their exclamation that nothing but death could break their bond of love could rightly be seen as ominous. Both singers do credit to their increasingly desperate situation. Tassis Christoyannis, whom I saw as Don Giovanni, sings impressively about his implacable hatred as the tyrant Danaüs. His rage is presented not as mere scenery-chewing, but the result of a deep, even paranoid suspicion. The opera's finale finds the chorus proclaiming the ceaseless punishment of his wickedness. Significantly, the tyrant himself is rendered voiceless.