Today is the day I have been dreading for more than a

month…a day that marks the end of the first phase of my Boeing 737 First

Officer training and the day the FAA tested my systems knowledge. I started preparing well before class

actually got started, but ground school officially began three weeks ago. As with any airplane I’m not trained to fly,

the first time I peered into the 737’s cockpit, the sea of lights, switches, gauges,

levers and buttons meant very little to me.

I must admit I was more than slightly concerned about what I had gotten

myself into and even wondered a time or two why I had elected to leave the

relative comfort of the MD80 and an airplane with which I was intimately

familiar.

Today is the day I have been dreading for more than a

month…a day that marks the end of the first phase of my Boeing 737 First

Officer training and the day the FAA tested my systems knowledge. I started preparing well before class

actually got started, but ground school officially began three weeks ago. As with any airplane I’m not trained to fly,

the first time I peered into the 737’s cockpit, the sea of lights, switches, gauges,

levers and buttons meant very little to me.

I must admit I was more than slightly concerned about what I had gotten

myself into and even wondered a time or two why I had elected to leave the

relative comfort of the MD80 and an airplane with which I was intimately

familiar.

With each day of class and each system mastered, the cockpit began to make a little more sense. One panel at a time, the 737 cockpit has become less of a mystery and more like home…small, cramped and noisy. Don’t tell my wife I said that!

The honest truth is that school isn’t much fun. I can’t name a single pilot who actually enjoys going to school on a new airplane. There may be people out there who enjoy the process, but I’m certainly not one of them. Of course, there are gratifying aspects of the training experience, but the rare moments of pleasure are often overshadowed by the stress of the process.

The majority of phase one took place in the classroom. I showed up on day one expecting this part of the course to focus primarily on aircraft systems, but by day two I was in the simulator with a hand full of airplane. Granted, I haven’t been through a new airplane course in 13 years, but ground school encompassed more than I expected and uncovered more than a few holes in my preparation, mainly in procedures and flying techniques that I wasn’t expecting to have to know at such an early stage. The idea was to teach the details of a particular system in class then hop in the simulator to see how it actually worked…and more importantly, what happens when it doesn’t work as designed.

During my first training session in the simulator, the syllabus called for pre-flight, before starting engines and taxi checklists only. But after those were all complete and with time to spare, the instructor asked, “Hey, you guys want to fly this thing?” What were we going to say...no? Not a chance. This is my first experience with an airplane equipped with a Primary Flight Display like the one equipped on the 737NG, so it was good to see it in action. It’s the sort of thing you can read about all day, but until you see it in action, it’s terribly difficult to grasp.

Yesterday, we attended what is lovingly known as “stump the dummy.” No, that isn’t an official name and no one but the students use the term, but it’s an accurate description of the day. After completing ground school, the assumption was that we knew everything there was to know about the airplane, and that was a bad assumption. So they sat us down in a room with an instructor who grilled us for hours. Not surprisingly, he discovered a few additional holes in our knowledge.

Today, we took three tests. The first was an FMS evaluation which we completed on an electronic trainer in one of the classrooms. We were required to prepare the cockpit for departure, load the FMS and demonstrate proficiency with just about anything we might need to do while on the ground or in flight. We didn’t get a grade on the FMS test, but we weren’t allowed to make any mistakes either…so I guess I got a 100 on that one. That’s my story anyway.

The second test covered emergency memory items. We were required to make a 100 on that one or we’d have to come back for another attempt. I’m amazed by the number and nature of the memory items on this jet. We had 14 procedures to recite and several of them were…well…verbose! Reciting such a long-winded emergency procedure when an engine is on fire or the air is being sucked from the passenger cabin just seems silly, but Boeing writes these procedures and we follow them to the letter. I strongly suspect this is an issue of liability, since the Boeing Company would most likely wash their hands of any accident where the crews didn’t use the accepted manufacturer’s procedures.

With respect to memorizing the emergency procedures, we basically memorize them two ways…verbatim, to satisfy the instructors and the FAA, and practical action, where we’re more concerned about completing the procedure quickly and correctly than we are about getting every insignificant word in the right place.

I made a 100 on the test, so on to the third and final hurdle.

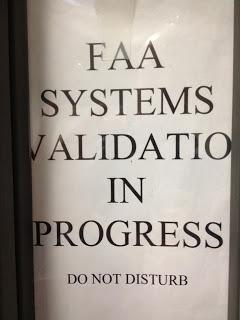

Preparing for the systems exam is where I spent most of my efforts. The last time I did this, the systems validation consisted of a one on one oral exam. That’s my preferred method primarily because I enjoy talking about airplanes and I’m much better at verbalizing my knowledge than I am at interpreting a written exam. Unfortunately, the current method for testing our systems knowledge is by written exam.

From a bank of questions that we never saw ahead of time, the computer randomly generated a 100 question test. It may be a flaw in my personality…I choose to think that it is not…but merely passing this exam would not be good enough. I spent the better part of a month before class started learning this airplane for a number of reasons. First, I wanted to reduce the stress level as much as possible. Second, I genuinely want to know as much about the airplane as I possibly can; I think my passengers deserve that. Third, I wanted to ace the test.

I made a 99 on the exam…and I’m ticked that I missed that one question!