Not that lockdown was a new concept even in the mid-17th century. The Byzantine emperor Justinian tried to lock down Constantinople in the 6th century to prevent seamen and traders bringing the plague into the city. He imposed quarantine regulations but ultimately they were ineffective and at the height of the infection, the citizens of the greatest city on earth were dying at the rate of 5,000 a day. That outbreak of plague effectively brought an empire to its end. Later, in the 13th century, notably in Italy and France, there were more successful attempts to impose cordons to protect individual towns and cities from the waves of plague like the Black Death that periodically engulfed the continent.

What marked the example of Eyam out from other lockdowns was this: the measures that the people of that Derbyshire village took in cutting themselves off were not to protect Eyam from infiltration of disease (it was already too late for that) but to contain the pestilence within their bounds and not let it spread to neighbouring villages or to the nearby city of Sheffield. It was a remarkable act of self-sacrifice and one that touches me personally, for members of my own family lost their lives in Eyam during the fourteen month lockdown.

gravestones and tombs in Eyam churchyard

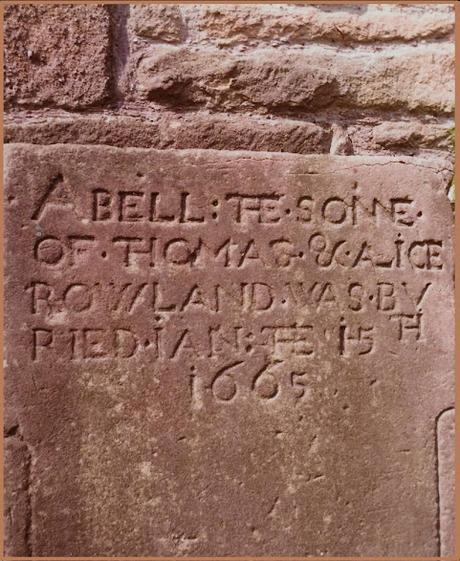

Here's how it happened. The plague arrived in Eyam in August 1665 in a bale of cloth sent from London to the village tailor. His assistant opened it to air it and a host of plague-carrying rat fleas were released. The unfortunate assistant was the first to die, within a week, and many other villagers soon contracted the disease. The village rector met with his parishioners and persuaded them that the moral thing to do was to isolate the whole village. An exclusion zone and warning signs were set up around the parish boundaries and amazingly no one left the village during the whole period. Eyam was self-sufficient to a degree but appealed by notice for foodstuffs from outside and these were duly provided t regular intervals at a boundary stone which was disinfected daily as was the money that was left to pay for the produce. Strict hygiene rules and social distancing were practised within the village with, for instance, the regular church services moving to an outdoor location. And plague victims were interred not in the churchyard, but close to their houses, to speed up the burial process and to minimise the movement of plague-ridden corpses.My paternal ancestor Abel Rowland (son of Thomas and Alice) is buried in Eyam churchyard (see his gravestone pictured below). He had the good fortune to die at the beginning of 1665, just months before the plague hit the village. Of the 800 inhabitants, 260 died of the plague in a 14 month period, statistically way higher per capita than the death rate in any other village, town or city in the land. That's members of 76 different families, the Rowlands among them. Such collectively bravery.

Abel Rowland's gravestone in Eyam churchyard (photo: Ray Rowland)

There was an understandable upsurge in interest about Eyam, the plague village, during the recent Coronavirus pandemic - and by the way that hasn't entirely left us, as in England there are currently about 1,000 new cases per day and despite the vaccination programme nearly 3,000 people right now are hospitalised with one variant or another - but my interest predates Covid, back to my father's family tree investigations in the 1970s. He grew up in Bakewell, some 4 miles from Eyam as the crow flies, and conducted extensive research into the parish records of the villages in the locale: Ashford, Baslow, Eyam, Hassop, Over Haddon, Rowland (yes, a family seat of sorts), Stoney Middleton and Tideswell. Our ancestral connection to Eyam led me to research more and I made the remarkable story of what had happened in the plague village into an English and Drama project for the year ten children I taught at a comprehensive school in north London in the late 1970s.Of course it's impossible for me to write about Eyam and lockdown without referencing obvious parallels with the Covid years and to take our present government to task. The fact is that the UK used to have the best and most well-maintained measures in place to combat a major health emergency (be that epidemic or pandemic), and this according to regular World Health Organisation audits. For decades we were best-in-class. That all started to change when the Tories got back into power in 2010. Cameron's coalition government made the decision to reduce funding for pandemic readiness and this trend only accelerated once the Tories were in complete control after the 2015 general election. The number of hospital beds reduced, stocks of PPE were not renewed, respirators and ICU facilities were not maintained to previous levels and so by the time Covid-19 arrived at the beginning of 2020, the UK was way down the list of well-provisioned countries, our emergency plans were rusty and our ability to react effectively to the pandemic was seriously impaired - as we all know now and as the ongoing enquiry will ultimately document in forensic detail. Tory apologists say it was a calculated risk to slash spending in the decade and that we just got unlucky. 24 million people (a third of the population) contracted the disease and a quarter of a million died as a result. Not good enough. The UK has consistently been in the top ten worst impacted countries in the world and we're still there (number 9 currently).

To compound matters, our own cavalier idiot of a Prime Minister started off claiming it was all a lot of fuss about nothing and ended up on a ventilator himself, then there was all the flouting of lockdown regulations by government officials and advisors (with Cummings and Co. fleeing the capital much as Charles II had done in 1665). But far more pernicious was the scale of cronyism and profiteering that went on as a rash of contracts for making PPE, for building respirators, manufacturing test kits, throwing together 'Nightingale' hospitals, outsourcing lab capacity went to firms in which Tory MPs or their immediate families had a strong financial stake. I hope the enquiry will not shirk from disclosing the true magnitude of the hundreds of millions of pounds of tax-payers' money thus misspent.

Let's hope that when the next pandemic arrives, for there will be one at some point, useful lessons have been internalised from the Covid years.

a plague doctor

To send you off with anger in your hearts for the grasping, greedy, incompetent crew (Cummings, Dorries, Gove, Hancock, Johnson, Kwarteng, Patel, Truss, Zadawi and all), my latest incendiary poem.A Plague Doctor Writes...A pox on you rats and fleas of Westminster I say!A plague on both your houses, such a verminousself-serving horde. No sooner had you unfurled your contaminated roll of shoddy than suddenly poured forth such contagion, an overwhelming devilment of virulent spores which has infectednot only Commons or Lords but the wider body politic and brought our misfortunate land downto its very knees. A pestilence on the mop-head of that festering jester, clown prince of calumny.But we need deliverance from the whole bunchwhose stench has become insufferable, beyondwhich plasters, vinegar poultices, smoking sageor sprigs of lavender could mask. You should allbe torched. My prescription? A mighty bone fireof all your vanities! I urge that a conflagration fit to purge us of your pestilence should rage soon.Thanks for reading, S đŸ’€ Email ThisBlogThis!Share to TwitterShare to Facebook