I received an invitation from a friend and former professor of mine inviting me and a number of his other students and colleagues to view Tarkovsky’s Stalker (Сталкер, 1979) at Chicago’s Gene Siskel Film Center on a humid Saturday night at the end of July. I wasn’t surprised to find that only a handful of people responded to the invitation, and most of that small group ended up cancelling. While only a small group of us attended the film, we were joined by fifty or sixty other die-hards. It’s not exactly a date movie.

Those familiar with the work of Andrei Tarkovsky will be hard-pressed to summarize his work with a single word. For the small group of people willing to tackle complex images with complex ideas, the films of Andrei Tarkovsky are like long-form invitations to a no-holds barred, philosophical free-for-all. The prospect of this is what makes Tarkovsky appealing to some and confusing to others. Given enough time, I did come up with a single word: an evening at the movies with Tarkovsky is exhausting.

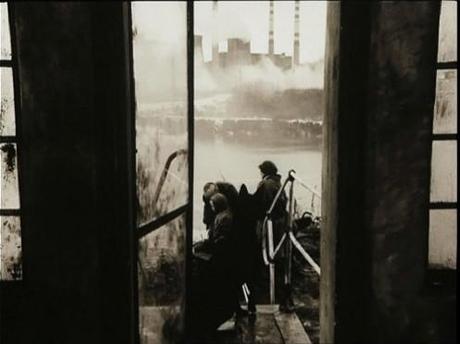

The film begins in a sparse, impoverished bedroom on the frontiers of a decaying industrial landscape. A passing freight train shakes a water glass on the table. A rotting wooden floor glistens with a shining, irascible dew. The walls are stained with water and chemicals. A machine hums in the distance. The Stalker leaves his home, against the wishes of his wife, and heads to a makeshift pub, where he meets the Writer and the Professor. They climb into a jeep and sneak through alleys, railways and abandoned garages to sneak through the barricades, where they are shot at and pursued. While it all looks faintly Soviet, everything is simultaneously indistinct.

Tarkovsky uses sepia-toned film for these portions, and when the trio finally arrives in the Zone, Tarkovsky switches to color film. Watching the 35mm reel projected on a large screen really served to dramatize the shift between these two types of film. The ‘Zone’ is filmed on the grounds of a long-abandoned power station in Estonia where nature has already worked to reclaim the crude, concrete structures and military apparatuses with flowers, roots, mud and earth. The effect is as haunting and beautiful as it is unsettling and portentous.

Much of the nuance and subtlety used in the Russian screenplay is lost in the translation to English subtitles. At best, the subtitles of this particular version provided strong hints at what was being said, though according to the Russian-speakers present at the screening, much of the poesy and rhythm of the language falls silent on our monolinguistic ears. Nonetheless, we glean a lot from their conversation, even if we’re tone-deaf. Here they talk about Art, Philosophy, Poetry, God and all the other Big Ideas. At the center of their conversation, however, is the subject of Desire. While ‘Stalker’ may be a film about everything, Tarkovsky wouldn’t be able to get at ‘everything’ without ultimately confronting the terrifying entity of Desire.

But to call ‘Stalker’ a two-and-a-half-hour film about Desire doesn’t do it justice. Like all other great films, there is something deeply spiritual about ‘Stalker.’ I won’t pretend to write as comprehensively about this aspect as Robert Bird does in ‘Andrei Tarkovsky: Elements of Cinema’ or other essayists do in Black Dog Publishing’s ‘Tarkovsky,’ but while watching Stalker, one can’t help but feel that he or she too is on a spiritual journey.

There is a moment towards the beginning of their excursion into the Zone where the Stalker points out their eventual destination, which is a mere 200 paces away. In the Zone, he says, the correct way is never the shortest. The Writer, fueled by impatience and alcohol, does not see the sense behind this and tramples defiantly through the grass. As he nears, he is blasted with a gust of wind and the voice of a man demanding that he go no further. None of the travelers are sure to whom the voice belonged, though like the quickly-sobered Writer, we aren’t sure that we’d like to find out. While this concept of the unexplained might upset the practical sensibilities of the Traditional American Moviegoer, this poetic trope serves to create an effective tool for exploring the auspices of the subconscious.

Freudians can have a heyday with the imagery in the film (such as the explorers treading into the Meat Grinder; a long, dark and wet drainage pipe), though in a way more aligned with Tarkovsky’s spiritual idealism, ‘Stalker’ is an exercise in metaphysics. The Writer, the Professor and the Holy Fool tread through a maze of wreckage and decay to directly confront the intangibility of their desires. The Writer wonders at one point how it is we can know what we truly desire. On the one hand, he says, my consciousness wishes for the triumph of vegetarianism; though all the while, my subconscious longs for a juicy steak. As my former professor noted after the film, if we could articulate our true desires, they would no longer be desirable. The men eventually find the room, though they all collapse in total emotional and spiritual exhaustion upon its precipice.

I suppose Tarkovsky could have ended the film there as we saw the men reveling in their spiritual wreckage, but instead, Tarkovsky brings them back out of the Zone and to the bar – joined this time by a dog who supposedly followed them back (again, don’t ask). The Stalker is reunited with his wife and daughter, who he affectionately calls ‘Monkey.’ She is paralyzed from the waist down and apparently mute as well, marred by the toxins and pollutants plaguing their home landscape. Yet, rather than reverting to the existential nihilism dominating contemporary cinematic parlance, Tarkovsky ends the film with a strange and ethereal promise.

Monkey sits at a table, little tufts of cottonseed drifting through the open windows. A jar and two glasses sit on the table. We hear a train pass and recede. The girl rests her head on the table, and a glass begins to move – we assume telekinetically. She pushes the glass to the end of the table, and repeats the experiment on another glass, pushing it off the table. It is a haunting final scene; stigmatizing language on one hand and elevating the spiritual on the other. It’s a genre of spiritual optimism rarely expressed in modern films, save for the rare gem like Terrence Malick’s Tree of Life.

The film exhausted us, so we abandoned our original plans to go out for a beer afterwards. Perhaps it was for the better. Some things are best reflected upon in silence. I often revisit these places in my dreams, and Tarkovsky prays when I cannot.