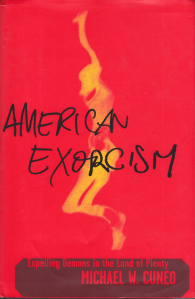

About the last people, ironically, that you’ll find researching demons are religion scholars. That’s perhaps a slight exaggeration, but there’s an embarrassment to the topic that serious academics just can’t shake. Nobody wants to be thought truly believing in that stuff. Michael W. Cuneo, who teaches sociology and anthropology at Fordham University, isn’t afraid to look. His American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty is a user-friendly, often witty look at what is an amazing phenomenon. Exorcism had pretty much gone extinct by the middle of the twentieth century. Then The Exorcist happened. Cuneo makes no bones about it—Hollywood wrote the script on what was to become a somewhat bustling business through the end of the millennium and beyond. And it wasn’t limited to Catholics. Protestants, mainly of Evangelical stripe, cottoned onto Deliverance ministry and joined the fray against the demonic.

About the last people, ironically, that you’ll find researching demons are religion scholars. That’s perhaps a slight exaggeration, but there’s an embarrassment to the topic that serious academics just can’t shake. Nobody wants to be thought truly believing in that stuff. Michael W. Cuneo, who teaches sociology and anthropology at Fordham University, isn’t afraid to look. His American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty is a user-friendly, often witty look at what is an amazing phenomenon. Exorcism had pretty much gone extinct by the middle of the twentieth century. Then The Exorcist happened. Cuneo makes no bones about it—Hollywood wrote the script on what was to become a somewhat bustling business through the end of the millennium and beyond. And it wasn’t limited to Catholics. Protestants, mainly of Evangelical stripe, cottoned onto Deliverance ministry and joined the fray against the demonic.

American Exorcism reflects Cuneo’s personal account of attending exorcisms. As he puts it at the end, no fireworks occurred. In fact, he’s skeptical that demons exist and he strongly suspects exorcisms work in the same way that a placebo does. He’s well aware that the majority of people he met and talked with in the making of this book disagree on that point. Cuneo himself attended at least fifty exorcisms, both Catholic and Protestant, and shysters among the exorcists were rare. Most were sincere, devoted people who are helping others in distress for no fees, no glory, and no promotion. They see a need, believe they know the diabolical cause, and take the devil by the horns (metaphorically speaking).

There is a solid mistrust between academics with their studied skepticism and exorcists with their eyewitness accounts that defy belief. Cuneo suggests that even what they think they see may not really be happening in the real world. My question, coming down to the end of the fascinating book, revolves around what exactly this real world is. There can be no doubt that present day concepts of exorcism are largely based on “the movie.” Cuneo seems just a bit reluctant to say what I also declared in my forthcoming book—pop culture, the movies, dictate reality for many people. At least in the realm of religion. Sacred institutions have lost their authority to make ex cathedra pronouncements about what is real and what is not. Few bother to, or can, delve into the tedious work of reading academic studies on the subject. It’s far easier to let the unseen presences behind the camera take over. Isn’t that what possession is about, after all?