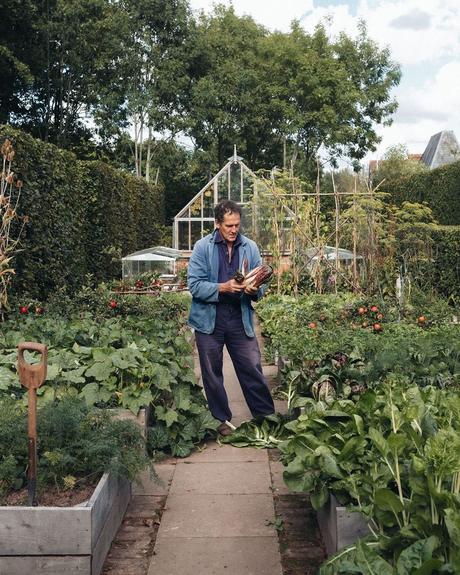

About eighteen years ago, Monty Don, the British horticulturist and human Peter Rabbit, penned an article for The Guardian titled "Dirty Dressing." It was about how to dress for the dirty task of gardening. "Never wear tight trousers," he advised. "Always buy trousers at least one waist size too big, make sure that the pockets are big enough to comfortably hold penknife, hanky, string, phone, pencil, labels, and perhaps a mint or two. [...] If you are not familiar with their joys, high-rise trousers are fantastically comfortable and keep your lower back warm. My children still squirm with embarrassment every time they see me in them (which is most days) but that is probably some kind of seal of approval."

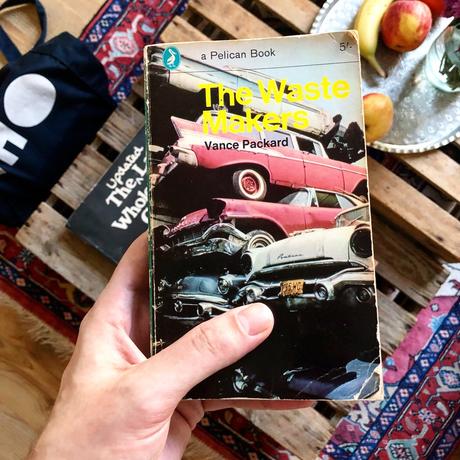

I remember being charmed by his intransigent views; each proclamation was stated matter-of-factly without the need for justification or even elaboration. "Do this, that, and the other thing." Sometimes, it feels like writers are unwilling to criticize anything nowadays or put their foot down on something they know. This admittedly includes me, a menswear writer who feels it's impossible to responsibly dole out generalizable menswear advice because people have different needs, personalities, and lifestyles.

So, in the last few years, I've been doing this series called "Excited to Wear," which isn't about things everyone should buy-no one can recommend those-but simply the things I'm most excited to wear for the new season. These posts allow me to get a bit Monty Don-ish, with my tongue firmly planted in my cheek and with the recognition that I'm only speaking about my personal views. Here are ten things I'm excited to wear as the weather gets cooler. There's also a fall/ winter playlist at the end for you.

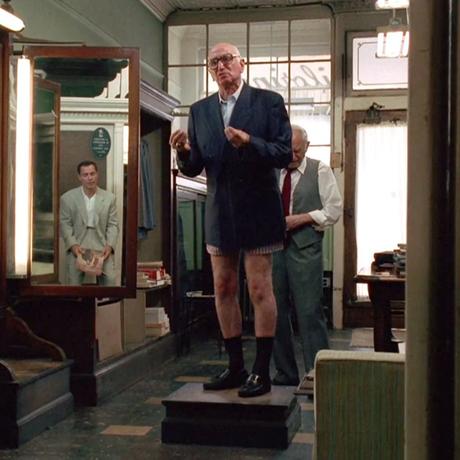

When I first got into tailoring, I worried about crossing the line and ending up on the wrong side of traditional. I stuck to tweeds in unassailable patterns such as houndstooth and herringbone; I eschewed gilt buttons because I thought they were too Old Money. When it came to slip-on shoes, I thought penny loafers were fine because they still had a whiff of everyman credibility, but tassel loafers were so obviously privileged that even Yale graduate George HW Bush used them as an epithet.

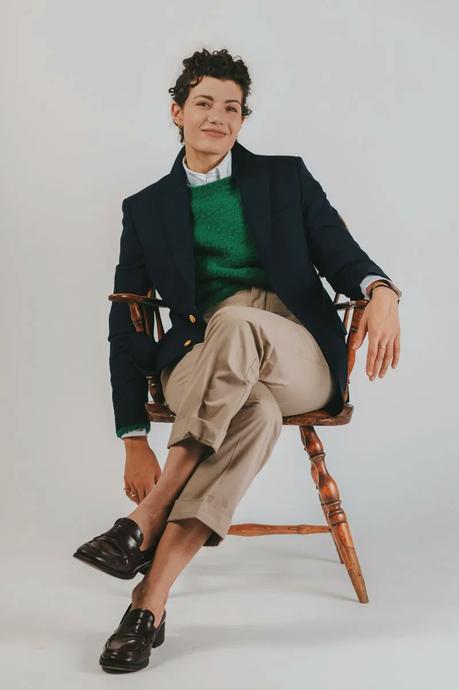

Over time, whether because of age or growing confidence, I've been drifting in the other direction. I'm more interested in the fustiest of tweeds, such as what you'd expect to be worn by an elderly man living on the Scottish highlands. I like tassel loafers more than their penny-strap counterparts. And I've been really into blazers.

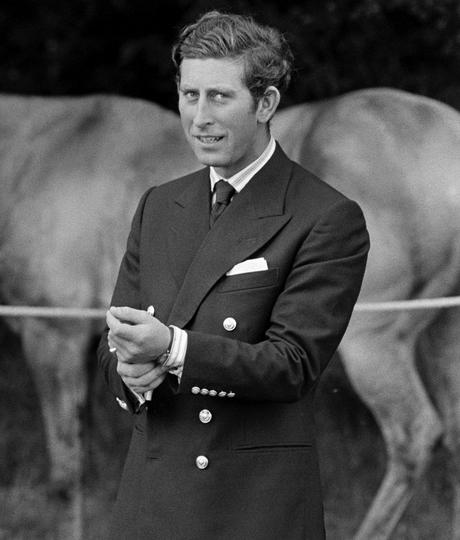

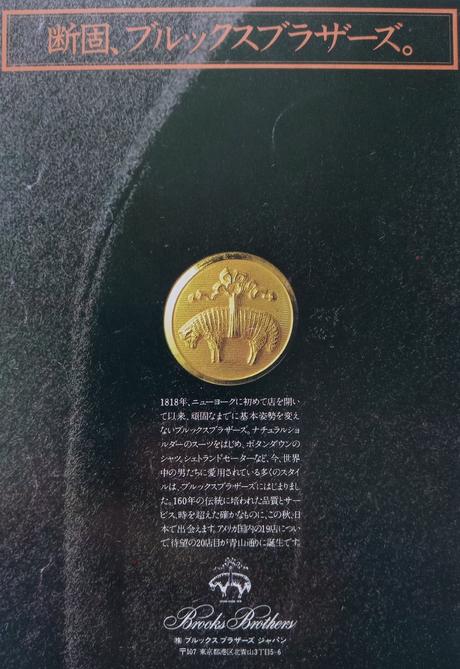

There are two often-recited stories about how blazers got their name. The first is that the term was initially applied to the red jackets worn by members of the Lady Margaret Hall Boat Club, which were so bright that they visually "blazed" on the blue waters. The second is that the term was used for the navy serge uniforms that the Captain of the HMS Blazer decorated with gilt shank buttons when Queen Victoria made her unexpected visit. The blazer's true origins are murky, but we know one thing for sure: the term today is chiefly used to describe tailored jackets, often navy in color, decorated with metal buttons, although sometimes it's also used to refer to the boldly striped jackets worn by members of rowing clubs. Such metal buttons typically carry an organization's insignia, signifying the wearer's membership or association.

In the genus of tailored clothing, which is already on its way to extinction, authentic blazers have gone the way of the dodo. While searching for gilt buttons die-stamped with the crest of my alma mater, I discovered The Connecticut Store recently closed. They were the best online source for buttons made by the Waterbury Button Company, America's last and most storied blazer button manufacturer. Before their closure, they carried Waterbury's entire catalog (almost), which meant you could get buttons for almost any school or trade organization. Apparently, Waterbury's parent company felt the licensing fees for each university became unworkable, particularly as the demand for these buttons declined, so now they only make them upon a university's request. Ben Silver also recently exited the blazer button business entirely. "Not enough people were buying them," a sales rep told me. If you want blazer buttons nowadays, you're mostly limited to ones featuring a fashion brand's logo or some faux aristocratic crest.

I have two blazers: a single-breasted made from tropical wool, which features gilt buttons die-stamped with the crest of my alma mater, and a double-breasted made from a heavier serge, which has gilt buttons stamped with California's state seal. The second is less satisfying because the insignia doesn't feel as personal (hence my search for more alma mater buttons), but I'm still excited to wear it. My friend Peter notes that metal buttons are the easiest way to ensure a navy DB is unambiguously not an orphaned suit jacket. "You can choose serge or hopsack, add swelled edges or patch pockets, but most people won't notice those details," he said. "Metal buttons, conversely, are the time-tested distinction and arguably the most obvious."

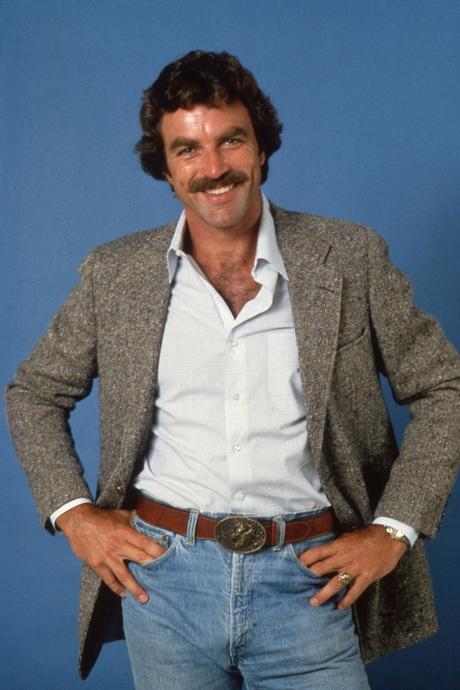

Blazers look great with tailored trousers and oxford button-down collars or dressed down further with jeans, Western shirts, and cowboy boots. They can be preppy, kingly, artsy, or rock-and-roll. While it's hard to get gilt buttons die-stamped with the insignia of certain organizations nowadays, you can still find handsome brass buttons on eBay or Etsy for about $50/ set. Add them to tailored jackets made from navy hopsack, black velvet, or tartan wool. The best thing about the DB version is that the flappy fronts add volume and shape when the jacket is worn open. It's like a cardigan but with a more flattering shoulder line and lapels that cross over the body in an armorial way.

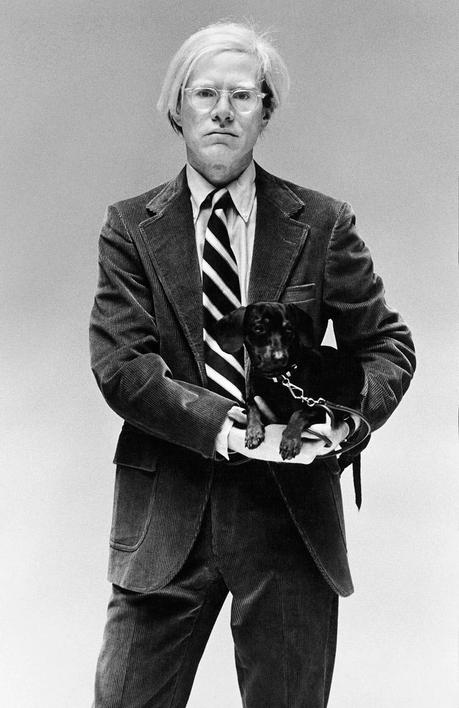

The Corduroy Appreciation Club holds annual meetings most years on November 11th, the date that most closely resembles the vertical ribs on corduroy. At their fifth annual Grand Meeting in 2010, my friend Jesse Thorn delivered a rousing defense of this beloved fabric. Velvet, he asserted, is evil, worn by knaves, scoundrels, and dictators who gather together nightly to toast to their latest swindles. Corduroy, on the other hand, is noble. It's the fabric of workingmen decompressing before a crackling fire, students cracking tomes open in the library, and farmers rolling up their corduroy sleeves to bring in the fall harvest.

"For a thousand years, corduroy has stood for what is right in our lives," Jesse said. "Intellectual rigor. Fresh air. The comfort of a crackling fire. It is a fabric as forgiving and enduring as our spirits at their best. What's truly special about our fabric is that it a fabric for being and for doing. For relaxed enjoyment and for taking care of business. For reading ancient tomes and for building great societies. Corduroy is the fabric of living."

We know this is true because corduroy is one of the few tailoring materials that improves with age. Slick worsteds are best when freshly pressed and clean; woolen flannels lose their charm once they become baggy and threadbare. But corduroy looks good rumpled, its plush ribs crushed and patchy. There's something democratic about corduroy because you can't buy or imitate the visible marks of authentic wear. The more time and use you put into a corduroy garment, the better it looks.

About ten years ago, I bought a single-breasted corduroy suit in the color of a fox squirrel's belly. It admittedly sat untouched for the first few years, mostly passed over for tweed sport coats and whipcord trousers. The late Charlie Davidson, who dressed jazz legends such as Miles Davis and Chet Baker at The Andover Shop, once said that tailored jackets need to hang for a year before he'd wear them. So perhaps my suit just needed to marinate. With due time, I've found it to be a useful garment around November, particularly for going to Thanksgiving dinners. Worn with oxford button-downs and suede loafers, it makes you look polished and presentable without any of the stiff formality that can be inherent in tailored clothing.

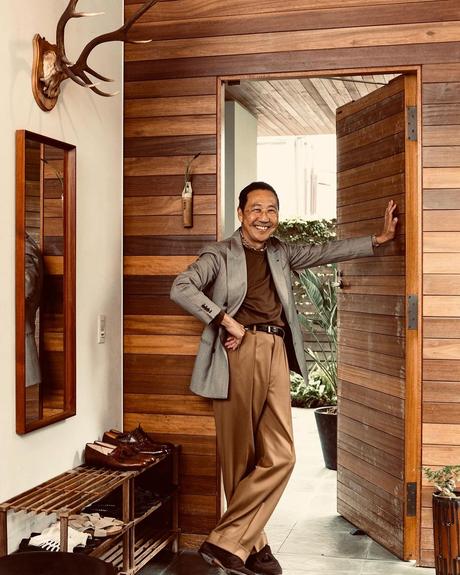

I'm looking forward to breaking out my corduroy suit, five-pocket cords, and RRL corduroy work pants this season. The pants go well with things such as Shetland knits, chambray work shirts, and trucker jackets. If you primarily work from home, five-pocket cords are a softer, more comfortable alternative to raw denim. They make you feel dressed up without looking overly precious, particularly when paired with t-shirts and cardigans. Speaking of which, I've been eyeing Lemmermayer's alpaca cardigans ever since seeing this photo of Yasuto Kamoshita.

Back in the day, men's dress was governed by TPO (time, place, and occasion), which is how we got terms such as morning coat, dinner suit, and smoking jacket. No one cares about these rules anymore, but they haunt our ideas about aesthetics like a specter. A navy, one-button, single-breasted, peak lapel suit made from a glimmering wool-mohair blend looks best worn at night to upscale restaurants because of the historical legacy of eveningwear, whereas a lumpy, brown, three-roll-two tweed looks perfectly at home while drinking a pint at a pub during the afternoon.

Options: Bryceland's. I also like these fatigues from Filson, Buck Mason, RRL, Engineered Garments, and J. Crew. Additionally, you can get post-war German Army Bundeswehr cargo pants on eBay for pretty cheap. They're made from moleskin, but not the plus British kind. This feels more like canvas. Be sure to size up, as a size 32 will measure 16″ across the waist (so, not vanity sized).

In that sense, I'm excited to wear what I call "evening tweeds," which are country outfits you can wear to get dinner in the city. That means tweed sport coats in citified colors such as grey instead of the more rustic browns or olives, and then paired with charcoal whipcord trousers and black calfskin tassel loafers that gleam under moonlight. Worn with a white spread collar shirt and a black silk knit tie, this kind of outfit can look very dressy. Or it can be dressed down with a white snap-button denim Western shirt, keeping to the idea of a rustic outfit in city colors. For something a little more sophisticated, try a button-up shirt in ecru, which is white with a drop of grey or yellow. Plain white dress shirts worn with a dark tailored jacket but no tie can look sad, like the night sky without stars. By pushing the fabric towards ecru or bone, the open collar looks more intentional.

I had Sartoria Solito make me a jacket like this last year from this Fox Brothers cloth: slate grey, glen check, and in a slightly darker shade so that it can be more easily worn with mid-gray trousers. A lighter shade would require charcoal flannel trousers. This mid-gray herringbone tweed would also make for a good suit, which you can wear with black denim Western shirts. Plus, grey tweed jackets are a great accompaniment to jeans-blue in the afternoon, black at night.

When I visited Naples for the first time in 2012, my friend Gianluca Migliarotti, director of , brought me to a tailoring workshop in the ritzy district of Chiaia. It was nightfall, however, so I didn't have a good sense of where we were going. From what I could tell, he led me down one of the quieter streets, where we entered a courtyard, went up some marble stairs, and knocked on a wooden door that I could barely see in front of me. When the door opened, a softly lit room with warm red walls appeared, and standing in front of us was Antonio Panico, dressed in a navy suit, light blue shirt, burgundy oxford-weave tie, and black suede chukkas.

For those unfamiliar, Panico is a legendary Neapolitan tailor who once served as the head cutter at Rubinacci, then called London House, after the departure of Vincenzo Attolini, the man most widely credited with having invented the soft-shouldered silhouette that now defines Neapolitan style. It's said that Panico's cutting skills are so good that he once made a summer safari jacket out of a seven-ounce cloth, which is so light that it's traditionally reserved for papal clothing. As is customary in Naples, the tailor offers you a small cup of espresso when you enter their workshop, even at night. "Ve site giè pigliato o' cafè?," they'll ask ("Have you had coffee?).

I returned home from that trip still thinking about how elegant Panico looked in those black suede chukkas, which visually anchored the seriousness of his outfit while adding a dash of pleasant unexpectedness. I've wanted a pair of black suede shoes since, but held some reservations. Black suede risks looking at velvet, which ventures too far into dandy territory for me, and suede gets patchy as it ages. That can look charming in brown suede but potentially less appealing in black.

Last year, I finally purchased a pair of black suede tassel loafers from Morjas (the model appears no longer stocked, although they have Belgian and penny strap versions). I've found that black suede doesn't look right with spring/ summer outfits, but they come into their own during the cooler months, particularly in the evening. Black suede tassel loafers sit nicely with more formal outfits, such as suits in grey flannel or navy pinstriped worsted; penny strap versions can be teamed with oversized sweaters and tailored trousers in textured materials, such as flannel, moleskin, or corduroy. I still think more basic materials such black calfskin or brown suede are more useful and versatile, but black suede can be excellent for variety. I'm looking forward to wearing them this season, and when I do, I'll remember that night in Naples.

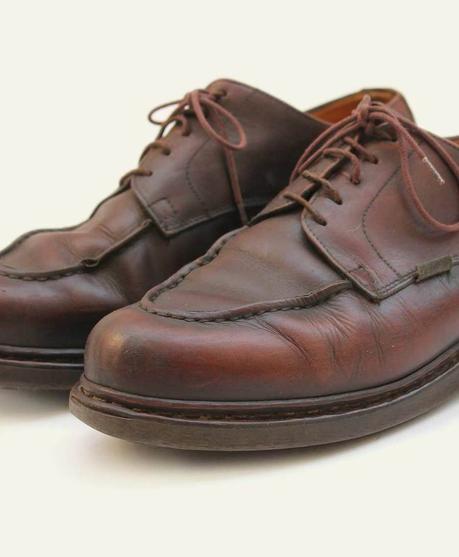

At his San Francisco trunk show last year, I met up with Seiji McCarthy, the Philadelphia transplant who moved to Tokyo to work as a bespoke shoemaker. When you close your eyes and imagine bespoke footwear, you likely picture those sleek Continental shoes shaped like New York pizza slices. McCarthy's shoes are different. Rather than overly finessing the details, he makes what I admiringly describe as "elevated Alden." The shoes have almost shaped toes, slightly higher side walls, and conservative styling. They're the Platonic ideal of American footwear, a natural anchor for three-roll-two sack suits, button-down collars, and polo coats. When McCarthy told me he draws inspiration from Ralph Lauren, I immediately thought: "that's why I like this guy's work."

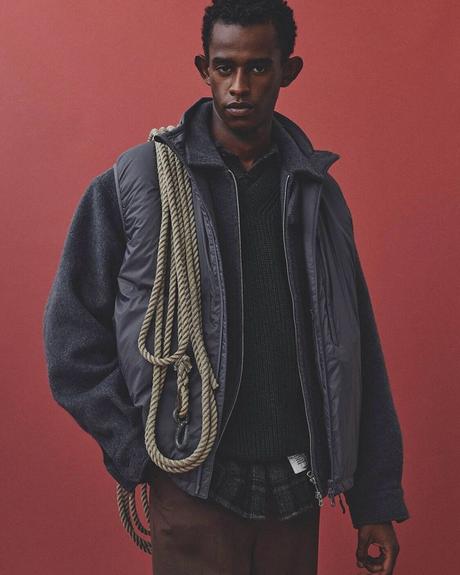

When I met up with McCarthy, he wore a navy double-breasted Tailor CAID blazer, blue Rubato chambray work shirt, suede Alden LHS loafers, and olive green Bryceland's P-13 cargo pants. I liked the outfit so much that I bought a pair of P-13s a few months later. The design is inspired by the USMC P-44s, a military cargo style coveted by vintage collectors and workwear enthusiasts. Like the P-44s, Bryceland's P-13s feature an unapologetic high-rise, generous leg, and spacious side pockets initially designed to hold military food ration packs. However, it's missing the flapped butt pocket that earned this style the nickname "monkey pants." I've always liked the design, but I didn't want to explain to friends and co-workers that this wasn't a poop shoot but rather an incredibly cool mid-century detail initially made to hold a camouflage poncho. It's difficult enough explaining how patched pockets mean my sport coat is actually casual.

These P13s have become one of my favorite purchases this year. They go great with vintage tees, flannel work shirts, denim trucker jackets, chunky fisherman knits, and all-black Blundstone boots. The unfinished iron buttons promise to patina and rust with age, adding another layer of detailing. The only thing is that you need to size up (check measurements). If you purchase the unwashed version, as I did, you'll also find that they fit like cardboard initially, which throws off the silhouette. After a cold wash, the heavy cotton herringbone twill softens up nicely.

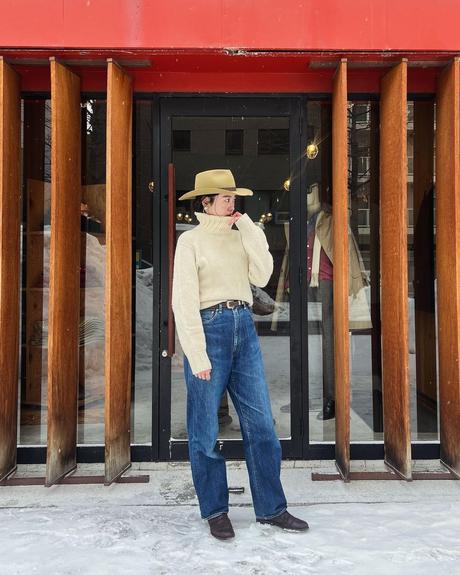

Nothing defines the American fashion experience more than the search for the perfect pair of jeans. Rummaging through racks and trying on endless pairs, finding that nearly all are too tight, too baggy, or not long enough in the rise. In the last few years, I've been into two specific cuts: a slim-straight leg that's more forgiving to my aging body than the APC New Standards that were popular twenty years ago; and bootcut jeans that have come roaring back with the revival of Westernwear.

I found the first through the recent Polo Ralph Lauren x Naiomi Glasses collaboration. They come in two variations, plain and embroidered, and in three colors ( off-white, taupe brown, and washed blue). I don't particularly like the pre-distressing on the washed blue version, but the other two have been my go-to on days when I don't want to think about how to dress. They have a slightly higher rise, which makes them easier to team with sport coats, and enough room in the leg that you don't look like John Tory.

There are lots of other models in this category worth considering: Resolute's 710 and 711, Orslow 105 and 107, Full Count 0105, TCB 60s, Kaptain Sunshine 1930s straight leg, 3sixteen CS, and Levi Vintage Clothing's 1947 501s (perhaps the most classic). Gustin recently loaned me a sample of a new higher-rise, fuller leg cut they've developed, which is set to be released later this month. I was very impressed. It's again a slightly higher rise, fuller leg cut without being baggy. I think of them as "grown-up jeans" for guys who are used to wearing slimmer styles but find that cut doesn't suit them in their middle age. Additionally, I was really impressed by the 1980s/ 1990s 501s that my friend David Lane recently posted (pictured above). He tells me that the ones with a six-button fly have a higher rise. It's always safer to buy vintage denim in-person since you can try them online, but if shopping online, try to get them from someone who can give good sizing advice. Wooden Sleepers has a bunch of vintage Levi's.

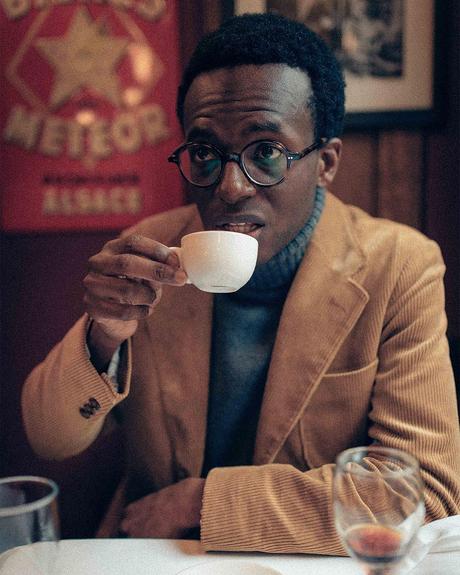

For bootcut jeans, Bryceland's 893 features a high rise, square hip, flat seat, and a gently flared leg that sits comfortably over cowboy boots. It's available in a brighter blue indigo denim (non-selvedge) and a Johnny Cash black sateen. The cut is inspired by vintage Lees, which Peter recently picked up on eBay (he tells me to look for the made-in-USA label and double-check measurements, as they're definitely not vanity size). My friend Willy, pictured above, has also been into Wrangler's bootcut. "They make me look like I'm 80% legs," he told me. Wrangler's online photos are not terribly inspiring, but when you see how Willy styles them, these $40 jeans become very tempting.

Centuries ago, the Inuit, indigenous to the Arctic regions of North America and Greenland, figured out something essential to their survival: you could stay warm in a frozen shelter. The secret to igloos lies in the snowflake's crystalline structure. When compacted into snow, the material is chiefly made of air, sometimes upwards of ninety-five percent. The Inuit know they need something with enough fluff for insulation, but also structure for building. So they cut blocks of wind-packed snow drift from the ground-halfway between packed snowballs and frozen ice-and then stack them into hollow catenary structures. Once inside, their body acts as a furnace, radiating out and circulating heat inside through convection. It's estimated that the interior of an igloo can be 40F to 60F warmer than its environment, just based on the person's body heat alone.

Outerwear works in much the same manner. Air pockets help retain heat, which is why parkas stuffed with fluffy down feathers or spongey synthetics are warmer than 22oz wool overcoats, which in turn are warmer than cotton trucker jackets. This season, I'm excited to break out a padded Monitaly bomber I purchased years ago. Made from deadstock parachute fabric, it has a big, round body with enough room to accommodate chunky woolen knits or cotton hoodies.

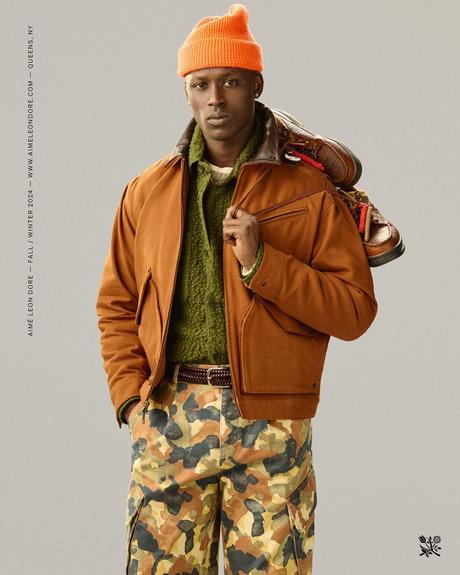

It also creates one of my favorite silhouettes: a circle stuck atop two legs. It's the look that Central Saint Martins graduate Fredrik Tjærandsen sent down the runway in 2019 when he dressed models in translucent rubber bubbles as part of the school's annual fashion show. The structures had a valve at the top, and once deflated, these surreal, shape-shifting spheres turned into shimmering dresses. This is also the same silhouette I admired as a bright-eyed youth, standing in line to get into nightclubs to see men participate in an emergent dance scene called freestyle. Back then, men wore a big rounded top, often in the form of an oversized anorak, Starter jacket, or bomber, which they layered over chunky knits or jerseys and then teamed with baggy jeans. To me, that silhouette has always been cool, evoking the edginess of youth street culture and the rugged masculinity of mid-century military uniforms. Check out the music videos for "Nas is Like," and "Survival of the Fittest" for style inspiration.

If you're interested in playing with a new silhouette this season, the lollipop shape is one of the easiest to incorporate since it shows up so heavily in workwear. A vintage Lee 101-J trucker jacket has dropped shoulder seams and a slightly cropped length, giving it a vaguely rounded shape. An MA-1 bomber will be even more bubble-like and have a thin, ribbed collar that goes well with hoodies underneath. For hoodies, I like the ones from Bare Knuckles this season. They're made from a heavy 450 gsm cotton, garment dyed, and then given an enzyme potassium spray to emulate a sun fading effect. The fit is slightly wide across the shoulders and body, with a cropped length to hit your waistline. Once tucked into a bomber, they help create the look and feel of a heat bubble surrounding your torso.

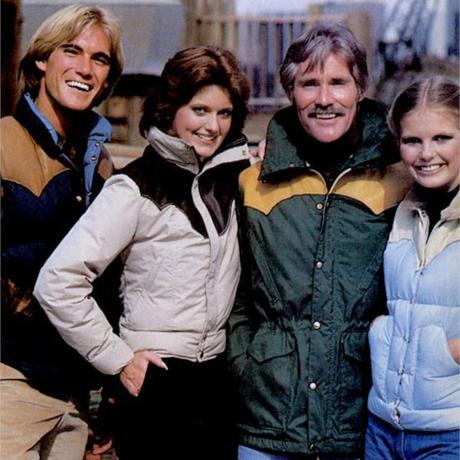

In the early 1970s, Francis "Cub" Schaefer was sitting in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, surrounded by a surplus of down comforters he couldn't sell under the label Rocky Mountain Featherbed. So he hired two clothing designers, Peter Carman and C'Anne Baker, to turn the material into down puffers and vests distinguished by a seamless, single-piece leather yoke inspired by Native American capes. They weren't the first to put a Western yoke in ski gear; the neighboring brand Powderhorn Mountaineering had been doing it for nearly a decade. Still, the jackets and vests proved popular with local ski instructors and their wealthy clientele who enjoyed wearing cowboy hats as part of the local ski scene. Soon, Rocky Mountain Featherbed was doing brisk business, seeing their Gore-Tex outerwear combined with Norwegian knits and Westernwear at nearby ski slopes. But after a dry winter and the maturity of some loans, the company went belly up in 1981, shutting down the operations of an outerwear brand with an unusual name that hinted at its blanket beginnings.

Like with many cool things in menswear, I only learned about the company when it was revived by some Japanese investors (this was the premise of David Marx's book ). A few years ago, I picked up a Rocky Mountain Featherbed Christy jacket from Mr. Porter during an end-of-season sale. I admit the price felt hefty for what I received-a nylon Taffeta jacket stuffed with 90/10 down-feather 700 fill power, finished with a sheepskin collar, and decorated with the company's signature leather yoke. But over time, I've come to appreciate how the jacket straddles the divide between cowboy and ski bum style. It has also opened me up to styling ideas that I describe as "1970s cold cowboy," which is what I imagine a ski instructor would have worn somewhere in the midwest-Colorado, Utah, or Wyoming-during that fabulous decade that saw glamorous tailoring and a Westernwear revival.

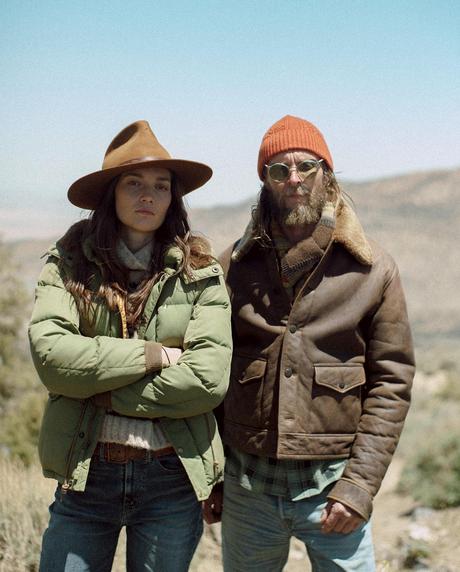

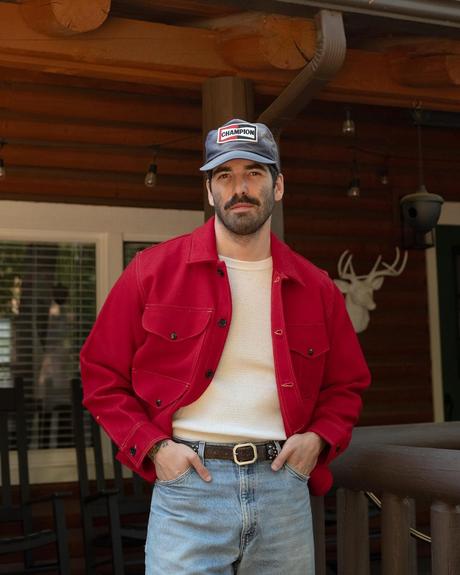

The key to the look is mixing and matching Americana, workwear, and Westernwear, often in a way that involves creative layering. Think: denim Western shirts, Fair Isle sweaters, mid-century Cowichan cardigans decorated with sporting motifs, slim-straight jeans or moleskin trousers secured with turquoise inlaid Native American belt buckles, Filson Mackinaws teamed with chunky turtlenecks and five-pocket cords, trucker caps or Stetson cowboy hats sitting atop Rocky Mountain Featherbed outerwear, chunky oversized sunglasses, and of course hiking boots. The Instagram accounts sideadjuster, masksantafe, and bozemanvintage are great for inspiration.

If you've been into menswear for a while, you likely already have a bit of prep and workwear in your wardrobe, perhaps even peppered with some Westernwear. So just try some unique styling combinations, such as wearing a thin merino turtleneck underneath a chamois shirt, teaming them with moleskin jeans and a pair of oiled suede roper boots. A Western yoked down vest and a chunky pair of sunglasses can finish the look.

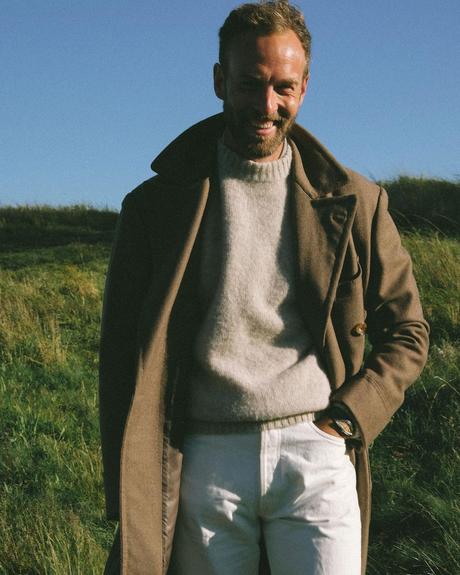

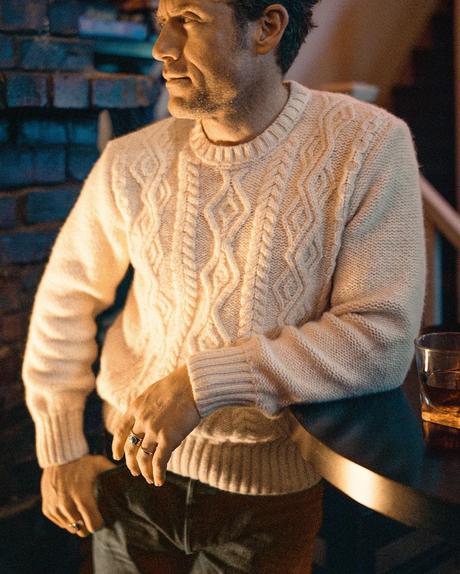

I'm convinced you only need two things to look stylish in winter: a big coat and a chunky, textured sweater. Mid-thigh coats, which tailors sometimes refer to as car coats, are more convenient if you drive, as they won't drag behind you and potentially touch muddy floor mats. However, they're an aesthetic compromise. Longer coats that come down to your knees or mid-calf have drama and verve. They create elongating lines and swish when you walk. In films, books, and TV shows, such dramatic outerwear is also a way for the director to communicate something. The menswear writer Bernhard Roetzel once noted that a man putting on his overcoat indicates his intention to leave; by taking it off, he announces he's arrived. "But a man who arrives without taking off his overcoat is signaling reserve, distrust, or just indecision." In his book , Max Frisch writes of a crowd standing outside a bar, everyone dressed in overcoats. With just those few words, he's depicted an unresolved situation.

If you get a voluminous overcoat, you need something to fill it. Big overcoats worn over just t-shirts or button-ups can make you look like you're wearing your father's clothes, the garment's folds swallowing up your body. Thus, it helps to have a chunky, textured sweater, such as these from the Japanese maker Okochi Meriyasu. The texture of these basketweaves and Shaker knits add visual interest without being the center of attention. Wearing a chunky knit helps fill up the coat's volume and balance the outermost garment's visual weight.

When shopping for an overcoat, consider how the sleeves have been constructed. The term set-in sleeves refers to when the sleeve is inserted into an armhole, much like you see on a t-shirt or dress shirt. A raglan sleeve is when a diagonal seam runs from your neck to the armhole. The first results in a squarer, more T-shaped shoulder line, which I think looks relatively more formal. The second gives a rounder shoulder line, which looks more relaxed and allows the coat to be more easily worn over another jacket (since you don't have to contend with where the shoulder seam ends up landing). I think there's room in a wardrobe for both styles, but if you have to choose, go with a set-in sleeve if you want to look more dressy and a raglan for something more casual.

A year after the release of , Bruce Boyer joined Jesse Thorn for a podcast interview , where Jesse gave him some light ribbing on ascots. After all, Bruce opened his book with a chapter on the gentlemanly accessory, which arguably should only be worn if you're about to declare that Professor Plum killed Colonel Mustard in the drawing room with a candlestick. "You're taking advantage of me now," Bruce joked. "Because I started my latest book, , with a chapter on ascots, and everybody says to me: 'Ascots, Bruce? C'mon. What are you, living in the 19th century?' I think I shouldn't have said 'ascots;' I should've said 'scarves.' My point was that a lot of guys don't know what to do with their necks. S ome guys' necks are okay, and some are not. And there's something you can do with your neck instead of leaving it to hang out there while everything else is nicely upholstered. If you don't want to wear a tie, that's okay, but a nice scarf at the neck is wonderful. You know the whole French nation is built on the idea of a scarf at the neck, Jesse."

I was skeptical when I first read Bruce's chapter on ascots, but nearly ten years later, I've come around. He's right: outfits often look better with something around the neck, whether an ascot, scarf, necklace, bandana, or neckerchief. I recently realized this while reviewing photos of Yasuto Kamoshita, arguably one of the most stylish men alive. He often wears a conservatively patterned neckerchief with the points neatly tucked into his shirt. Since the points are hidden, it's just a bit of color that peeks out from around his collar. Jason Jules, noted neckerchief enthusiast, wears them with the points out. My podcast co-host Pete wears longer bias cut scarves, which function a bit like a casual tie. A muffler can be worn with tailoring for a similar effect.

If you suspect you'll wear a neckerchief more conservatively and with the points tucked into your shirt, then any cotton bandana will do. But I've been really into . It's made from wool, which offers more texture, and the 21″ x 21″ size is big enough that the points don't look choked up your neck, should you wear the points out. When wearing one, a simple knot will do or you can try this one from Todd Snyder tying it like this so the points layer flatter. Can these sorts of accessories look affected? Yes, possibly. But, like with those brass button blazers and fusty tweeds, I care less nowadays.