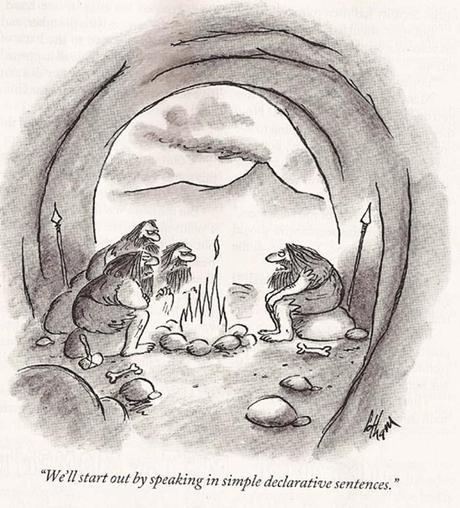

While contemplating the ways in which our thoughts are conditioned by language in the Sapir-Whorf post, I kept hearing Nietzsche commenting on the “metaphysics of language” in Twilight of the Idols: “I am afraid we are not rid of God because we still have faith in grammar.” In many of his books, Nietzsche hammers away at the idea that language simply reflects reality and accurately corresponds to things “out there” in the world.

There is too much slippage, or distance, between symbols arbitrarily assigned to signify the things “out there” for this to be true. Even when word symbols are assigned to something relatively definite (such as “dog”), these symbols don’t carry much meaning without a great deal of context. This, in turn, ensures that language will always be slippery, never quite getting at a speaker’s goal, objective reality, or absolute truth. Contexts are always ambiguous.

This is of course a constant source of individual frustration and cultural madness. Extremely bothered by all this, Wittgenstein spent the better part of his life trying to prove that language could in fact be objective and truthful. In the end, he was reduced to saying very little, indeed almost nothing. He thought this was the only way he could be truthful.

It seems exceedingly odd that natural selection should design such a thing. Selection is not of course an agent and it does not design anything. It is the imperfect communicative outcome of millions of years of evolution. Some might even call it a kluge.

In a new paper, Shigeru Miyagawa, Robert C. Berwick and Kazuo Okanoya propose that language is the merged product of two distinct kinds of communicative systems found in the animal world:

Like many evolutionary innovations, language arose from the adventitious combination of two pre-existing, simpler systems that had been evolved for other functional tasks. The first system, Type E(xpression), is found in birdsong, where the same song marks territory, mating availability, and similar “expressive” functions. The second system, Type L(exical), has been suggestively found in non-human primate calls and in honeybee waggle dances, where it demarcates predicates with one or more “arguments,” such as combinations of calls in monkeys or compass headings set to sun position in honeybees. We show that human language syntax is composed of two layers that parallel these two independently evolved systems: an “E” layer resembling the Type E system of birdsong and an “L” layer providing words.

This makes a great deal of sense, and goes some way towards explaining our naive faith in language. The layering of these two systems gives rise to language that always contains two levels of meaning, which sometimes work at cross or divergent purposes. Poets, of course, have known all this for a long time and hardly need an evolutionary explanation for it. The inevitable result of layering may be metaphor.

All of which brings us back to another metaphor, which John Gray recently discussed in an interview about his new book, which ironically is titled The Silence of Animals:

Spectator: You also say that “atheism does not mean rejecting belief in God, but giving up a belief in language as anything other than practical convenience.” What are you getting at here?

Gray: I was referring to Fritz Mauthner, who wrote a four-volume history of atheism. He was an atheist who thought that theism was an obsessive attachment to the constructions of language: that the idea of God was a kind of linguistic ideal. So that atheism meant not worshiping that ideal. But he took that as just an example of a more general truth: that there is a danger in worshiping the constructions of language.

Of course religions like Christianity are partially to blame for this. But for most of their history, these so called creedal faiths didn’t define themselves by doctrine. Instead they had strong traditions of what’s called Apophatic theology: where you cannot use language to describe God.

I have long suspected that the “ineffability” and “transcendence” so often associated with (Axial) religions is largely a product of language, which is in some ways ineffable and when played with long enough, can seem transcendent. Our imperfectly evolved symbols and speech are slippery and wonderful “things.”