“We propose the creation of a harmonious economic community stretching from Lisbon to Vladivostok.” With these words, Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin described last year his vision of “a unified continental market with a capacity worth trillions of euros.” Putin’s proposal came during a visit to Germany, where the Russian leader had also a meeting with German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

“We propose the creation of a harmonious economic community stretching from Lisbon to Vladivostok.” With these words, Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin described last year his vision of “a unified continental market with a capacity worth trillions of euros.” Putin’s proposal came during a visit to Germany, where the Russian leader had also a meeting with German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

The idea of a continental bloc stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean is not new. During his stay in Japan, between 1908 and 1912, the father of German geopolitics Karl Haushofer for the first time envisioned a transcontinental bloc from the Rhine to Yangtze, advocating a triple German-Russian-Japanese alliance that became known as the Eurasian Bloc. The signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact on August 23, 1939 and the neutrality agreement between the Soviet Union and Japan in April 1941 seemed to have created the conditions for the establishing of that alliance, since there were discussions about a possible Soviet adhesion to the Tripartite Pact.

Nevertheless, the idea of a continental bloc of Germany, Italy, Japan and the Soviet Union that would oppose Britain and the United States soon failed due Hitler’s racial prejudices: contrary to the russophile and eurasist German thinkers, such as Haushofer and Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, the Führer saw in the Soviet Union Germany’s main enemy, thereby giving the Anglo-Saxon Powers a chance to eventually invade Europe and put an end to the Third Reich.

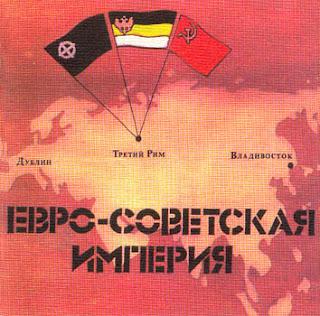

After the war, a Belgian veteran of the Waffen-SS, Jean Thiriart, called for the creation of a unified Europe, politically independent from both the United States and the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, when Washington approached Beijing in the 1970s, the ideologist of the European national communitarianism suggested a Euro-Soviet alliance against the Sino-American axis, in order to build a “very large Europe from Reykjavik to Vladivostok,” which he thought was the only way to resist the new American Carthage and billion-strong China. This is what led Thiriart to declare in 1984: “If Moscow wants to make Europe European, I preach total collaboration with the Soviet enterprise. I will then be the first to put a red star on my cap. Soviet Europe, yes, without reservations.”

THE EURO-SOVIET EMPIRE ENVISAGED BY THIRIART

In the words of Thiriart: “Between Iceland and Vladivostok we can unite 800 million people (at least for the sake of keeping the balance with the 1,200 millions Chinese) and yet find in the Siberian soil all that is needed to satisfy energetic and strategic requirements. I affirm that, from the economic point of view, Siberia is the province of the European empire most necessary to its viability. A great union of highly industrialized and technologically leading Western Europe with Siberian Europe, disposing of almost inexhaustible commodity reserves, will allow the creation of a most powerful republican Empire, with which nobody will but come to an agreement.” Thiriart died in 1992, but his basic ideas about the potentialities of a geopolitical alliance between Europe and Russia are shared by an increasing number of actors in the European political arena, partly as a result of Europe’s increasing dependence on Russian hydrocarbons.

In the words of Thiriart: “Between Iceland and Vladivostok we can unite 800 million people (at least for the sake of keeping the balance with the 1,200 millions Chinese) and yet find in the Siberian soil all that is needed to satisfy energetic and strategic requirements. I affirm that, from the economic point of view, Siberia is the province of the European empire most necessary to its viability. A great union of highly industrialized and technologically leading Western Europe with Siberian Europe, disposing of almost inexhaustible commodity reserves, will allow the creation of a most powerful republican Empire, with which nobody will but come to an agreement.” Thiriart died in 1992, but his basic ideas about the potentialities of a geopolitical alliance between Europe and Russia are shared by an increasing number of actors in the European political arena, partly as a result of Europe’s increasing dependence on Russian hydrocarbons.

With the world’s largest reserves of mineral and energy resources, Russia is currently the world’s largest oil and the second largest gas producer. From its side, with a generated GDP of € 12,268,387 billion in 2010, the European Union is the largest and one of the most diversified economies in the world, accounting for one fifth of global trade. A deeper cooperation between Brussels and Moscow would therefore be beneficial in many areas, such as trade, energy and last, but not least, security. As the main successor of the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation possess, in fact, the largest stockpiles of weapons of mass destruction in the world, including more than 2,000 operational nuclear warheads, and can play a primary role in the fight against terrorism.

Although many obstacles remain before a strategic partnership between the European Union as a whole and Russia can be established, the first results of increasing Euro-Russian cooperation have already been produced by the inauguration of the first line of the Nord Stream gas pipeline on November 8, 2011. And perhaps under the cold waters of the Baltic Sea lay not only the pipes of one of the world’s most secure gas pipelines in terms of environmental impact, but also the first geopolitical artery of a rising economic bloc stretching from the Iberian Peninsula to the Bering Sea: Eurossiya.