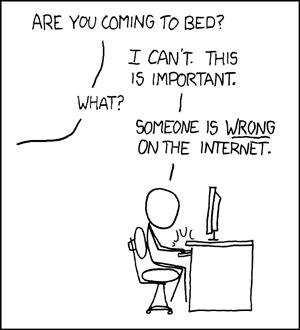

Would a formal reply make me this guy?

I've been exchanging views with Art Glenberg and his colleagues about a paper he published recently in Frontiers. I reviewed it, had reservations but eventually let it through, then published my concerns as a commentary on the original paper. Soliman and Glenberg (2014; S&G) then replied to my reply which I didn't know about until I noticed the commentary had a citation in my Google Scholar profile.I could simply publish a reply to their reply, but to be honest I'm not sure it's worth it; it feels a little too much like arguing on the internet. I'll link to this in the comments section of the Frontiers page, however, and if people think it's worth the DOI then I'll write this reply up as a formal submission. I'd be interested to hear from you all on this.

The short version of my reply is that in the process of dodging my criticism they concede it applies to them, and they swerve into a literature that doesn't help. I do think they've applied some serious and valuable consideration to the details of their proposal, though, so I think this has been a useful process.

The Basic Claim (Soliman et al, 2013)

Our perception of our upcoming interactions with the environment are scaled with respect to our current ability to implement that interaction. For example, fatigue makes hills look steeper (see this post reviewing a head to head on the topic between Chaz Firestone and Dennis Proffitt. Side note: writing those papers up for the blog tooled me up enough to review and sensibly critique Glenberg's paper, so score 1 for blogging!).

Soliman et al (2013) claimed that the anticipated effort of an upcoming social interaction with an out-group member should be larger than for an in-group member. Applying Proffitt's mechanism, they predicted that this anticipated effort should make the distance required to go engage in the interaction look farther, and this is basically what they found.

The Critique (Wilson, 2014)

My problem relates to a central part of Proffitt's theory: that this perceptual scaling is task-specific. Effort in one domain (e.g. making your legs tired) changes judged distances when you intend to walk that distance but not when you intend to throw that distance. As the head-to-head revealed, Proffitt considers this to be a non-negotiable feature of the theory. The problem for Soliman et al is that this means their proposed chain of events is neither predicted nor explained by Proffitt's theory. I wouldn't have minded so much but it was the central framing of their paper, so this issue matters.

The Reply (Soliman & Glenberg, 2014)

The reply has two parts; I'll handle them in the reverse order S&G present them.

1. Proffitt's stuff is entirely different from ours

S&G walk through the logic of Proffitt's work and compare it to theirs. They note that for Proffitt,

the manipulation phase targets one motor system and then tests the effect of the manipulation on perceived distance as the participant intends to perform another task. For example...participants are adapted while temporarily turned into throwing phenotypes, and then tested while in the walking phenotype. Typically, it was found that the visio-motor scale developed while in one phenotype did not transfer to the other...pg 2and then

In our experiments, however, no behavioral phenotype was turned on, manipulated, switched off, replaced by another, and then examined. Instead, our participants were walker-then-interactor phenotypes throughout....We believe that these subtle design differences render our original results and theoretical arguments immune to Wilson's critiques.pg 2It does, but at the cost of entirely rejecting their original framing, and my point was always that Proffitt's work could not possibly motivate or explain their work. As far as I can tell, this reply just admits I was right.

Given this, do they have a replacement motivating theory? Yes, but it's not going to save them.

2. End state comfort and motor contagion

Their new description for their task implies that instead of having two task specific systems that don't interact, they actually have people engaged in a composite task; not walking and then interacting, but walking-so-as-to-interact.There are well known examples of these kinds of tasks in which the later parts affect planning and execution of the earlier parts. The main example they cite is Rosenbaum's end state comfort effect. The classic example is reaching-to-grasp-and-turn an upside down wine glass; people adopt an initially uncomfortable upside down hand posture because this means that when they turn the glass, they end up with the hand the right way round in a comfortable posture. People are therefore not reaching-to-grasp, then turning; if they were, they would execute the first part more efficiently. Instead, they suck up the initial cost so that the whole movement is efficient and the final result stable. (I've done a little work on this in the past; Kent et al, 2009; van Swieten et al, 2010).

On the surface it sounds like this work applies nicely to S&G's study; but, as with Proffitt's work, as soon as you consider the actual mechanism at work the match fades away. These cases of 'motor contagion' all show that the earlier movements are reshaped in functional ways to serve the higher order task requirements. In the wine glass case the initially uncomfortable reach-to-grasp makes the overall reach-to-grasp-and-turn action more efficient and stable. S&G describe another study where grasping requirements affected locomotion over to the object to be grasped; but again here, the effect was that people adjusted their final steps to facilitate grasping the object.

S&G just don't have this set up. The increased effort of interacting with an out-group member will not be reduced by perceiving the distance to that person as farther away. Returning to Proffitt, people rescale distance perception when tired, for example, because that the distance really will be harder to cover and making it look that way facilitates effective planning. The upcoming social effort has no consequences for how hard it will be to walk over the distance (the root of my initial objection) and so making that distance seem farther is not a functional adjustment (the root of this objection).

S&G also mention example of tasks contaminating other tasks in non-functional ways (e.g. people unintentionally opening their mouths wider when simultaneously reaching for wider objects). This also doesn't help; this is about simultaneous actual actions affecting each other, not sequential upcoming actions.

SummaryI get a kick out of the fact that Glenberg takes me seriously enough that he thought it was worth replying to me. He reviewed my reply and was engaged and fair throughout. I disagree with him about embodied cognition but he's still a major name in the field and I've enjoyed having this out with him and his colleagues. I also like the fact that my reply really made them examine their task in detail. I wrote my commentary in the spirit of constructive criticism and I'm thrilled it's been taken as such. It's been a refreshing change, really.

All that said, I still don't buy it. All the similarity between these various tasks and Glenberg's experiment is superficial, at the level of the broad strokes verbal description of the effects. The actual mechanisms in play, either in Proffitt's work or the end state comfort effect, simply do not apply to Glenberg's study and so they still have failed to embody culture.

References

Soliman T, Gibson A and Glenberg AM (2013) Sensory motor mechanisms unify psychology: the embodiment of culture. Front. Psychol. 4:885. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00885Soliman TM and Glenberg AM (2014) How intent to interact can affect action scaling of distance: reply to Wilson. Front. Psychol. 5:513. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00513

Wilson AD (2014) Action scaling of distance perception is task specific and does not predict “the embodiment of culture”: a comment on Soliman, Gibson, and Glenberg (2013). Front. Psychol. 5:302. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00302