Graffiti on Henriques Street. Photo: my own.

On the night of the 29th September 1888, forty four year old Elisabeth Stride, a slight woman of 5ft 5ins with blue eyes and curling brown hair, familiarly known by her friends as ‘Long Liz’ and ‘Mother Gum’ walked the streets of Whitechapel in search of clients. Unlike the flashy Victorian prostitutes of popular imagining, she was dressed soberly and rather shabbily in a black jacket and skirt and black crepe bonnet, accessorized with a posy of red roses and ferns. A habitué of the local lodging houses, she was well liked for her cheerfulness, kindness and ability to sew and cook.

She was far from home, having been born Elisabeth Gustafsdotter on the 27th of November 1843 in Torslanda, a parish near Gothenburg in Sweden. As a teenager she had worked in domestic service in Gothenburg before becoming a prostitute in her early twenties. Poor Elisabeth went on to deliver a stillborn daughter in 1865, probably as the result of a venereal disease picked up from one of her clients.

A year later, in 1866, she moved to London in order to escape her past and start afresh, registering with the Swedish Church on Princes Square on the 10th of July that year and changing her surname to Gustifson. After a period as a maid, Elisabeth married a ship’s carpenter called John Thomas Stride, who was twenty two years her senior on the 7th of March 1869. For a while the couple ran a coffee shop on Upper North Street in Poplar and then another on 178 Poplar High Street before separating in 1877, whereupon Elisabeth entered the local workhouse. The couple had an off/on relationship after this but had finally ended their marriage by 1881 and by 1885, she was living with a labourer called Michael Kidney with whom she had a very unstable and occasionally violent relationship, fuelled by her alcoholism which led to several appearances in the dock for drunken and disorderly behaviour.

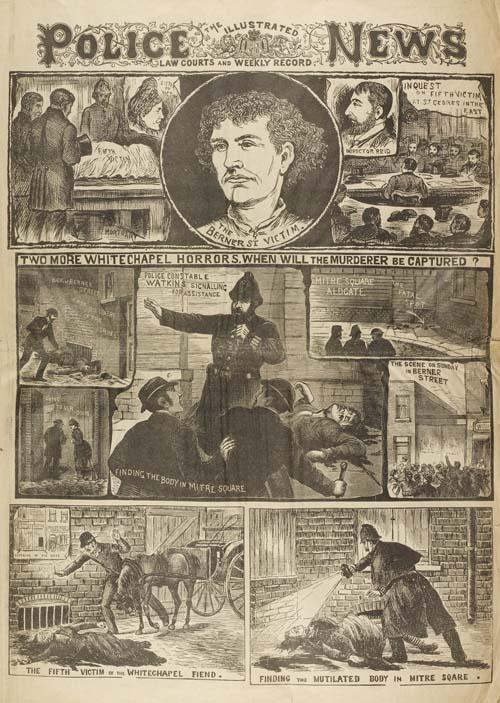

Illustrated Police News. Photo: Museum of London.

Her husband died of heart disease in October 1884, but it seems that Elisabeth had been in the habit of telling people that he and two of their fictitious nine children had been drowned in 1878 in the sinking of the Princess Alice into the Thames. There’s nothing unusual about this – the lives of the fallen women of Whitechapel were so awful and dreary that they often made up stories to make themselves appear more interesting and also in the hopes it might make their clients cough up a few more pennies out of pity. It’s sad though to think of this poor woman, so damaged by her past that she resorted to pretending that she was mother to a large brood of children and that she had been widowed in a terrible tragedy.

After her separation from her husband, Elisabeth’s life followed the not unusual for the time pattern of addiction, prostitution, abusive and short lived relationships and short tenures in workhouses and the notoriously grim Spitalfields lodging houses around Commercial Street and Brick Lane. It was a miserable, arduous and unhappy life spent wandering on foot between Commercial Street and Stratford in search of clients, punctuated with stops along the way to spend her meagre earnings on gin and porter and tell anyone who would listen about her husband’s tragic death, sinking beneath the grey water of the Thames and how she was now separated from her multitudes of children.

On the evening of the 29th September, Elisabeth left her mean lodgings on the dreadful Flower and Dean Street and went in search of clients. A witness later claimed to see her at 11pm near Berner Street with a man in a bowler hat and then she was spotted again forty five minutes later with another man, this time wearing a peaked cap. Then at 12.35, a PC William Smith claimed to have seen her on Berner’s Street, standing opposite a working men’s club with a man in a felt hard hat.

Where would Ripperology be without the various types of Victorian male headgear?

Less than half an hour after this last sighting, at around 1am, Elisabeth’s body was discovered by the steward of the men’s club in the next door Dutfield’s Yard when he led his horse and trap inside and almost tripped over her as she lay, her throat cut, on the cobbles just within the yard entrance.

Later, a witness, Israel Schwartz would come forward to say that he saw Elisabeth being attacked at the yard’s entrance by a man who threw her roughly to the ground. Clearly she had had a busy night but no money was found on her body, which adds to the possibility that the unfortunate Elisabeth was not actually murdered by Jack the Ripper but by someone else, who escaped justice thanks to the hysteria and panic surrounding the Ripper case in 1888.

However, although I know that for many, interest in Stride wanes when they discover that her ‘status’ as a Ripper victim is in some doubt, I think this is unfair as the fact still remains that she was horribly murdered that night and that whoever her killer was, Ripper or otherwise, he managed to evade justice for her death.

Roughly the location of the entrance to Dutfield’s Yard. Photo: my own.

Today, Berner Street is known as Henriques Street and is a shabby little road off the main thoroughfare of Commercial Road with its bathroom fittings show rooms and fabric shops. It’s a quiet spot, even now, as you turn away from the bustle of modern life and walk down past the school on the right to the corner where the entrance to Dutfield’s Yard once stood and where Elisabeth’s mangled body was discovered. Out of school hours, Henriques Street is generally pretty much deserted and at night it becomes almost eerie. When you recall how bustling and busy Whitechapel High Street and Commercial Road were at all hours back in the late Victorian era, you start to get a real appreciation for how flagrant the Ripper was.

People like to say that you can no longer appreciate what Victorian Spitalfields and Whitechapel must have been like as the area has changed so much in the past hundred years, but I don’t think that’s completely true as for me the beating heart of the city never really changes and although the appearance of an area may be cosmetically transformed over time, the essential atmosphere still remains and you can still very much feel it in the sad spot where Elisabeth Stride’s life came to an end.

Further reading: The Victims of Jack the Ripper, Neal Shelden, 2007.