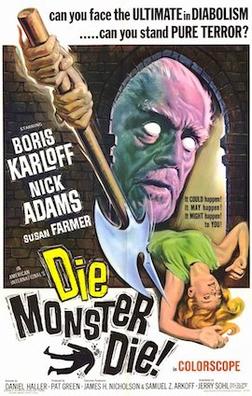

Bad movies can be therapeutic. While trying to find hope it sometimes helps to see that others are even worse off. This isn’t exactly Schadenfreude, but rather an awareness that your own efforts at self-righting aren’t so bad. Then there’s the hopeful monster theory, but that’s something different. Already the title of Die, Monster, Die! warns the viewer that this won’t be Oscar-worthy material. And despite his fame by 1965 Boris Karloff was still landing sub-par roles in such movies as this. Both the directing and editing are noticeably lacking, evident even to an amateur. A step backward may help; this movie is based one of my favorite H. P. Lovecraft stories, “The Colour out of Space.” This is, to me, his most Poe-like tale and could well serve as the basis for a film. Too much is changed here, however, to make it work.

Arkham is transplanted from its native New England to the old one. The love theme manages to interrupt the mood of dread Lovecraft used in his story. Nahum Witley’s use of the meteorite runs counter to the family’s reaction in the original. The screenwriting doesn’t build much confidence either. On the positive side, it feels like a fine little haunted house film from time to time, when the plodding plot doesn’t get in the way. For a scientifically aware visitor, Stephen Reinhart has no concerns about lingering, unprotected, around a major source of radiation. Although a few of the jump-startles work, the whole ends up feeling just a bit silly. Of course, I was watching to escape, for a moment, what life throws at you.

Like reading poorly written books, watching bad movies can teach you mistakes not to make. Movies can be an education rather than simply entertainment. Cinema is one of the great myth-making vehicles for modern culture and, unfortunately, big budgets are often (but not always) necessary to make them believable. Here is the hidden element of optimism, perhaps. H. P. Lovecraft stories can sell films. They also attach those who may be excluded from studio A-lists because, let’s face it, Lovecraft appeals only to a specific demographic. The title of this particular film buries the lede, however. No Lovecraft keywords (Dagon, Dunwich, Arkham, Cthulhu, or any of a host of others) clue readers in to what they might expect. Learning the film business from Roger Corman might’ve steered director Daniel Haller is this direction, I suppose. Whether he intended to or not, he produced a therapeutic result.