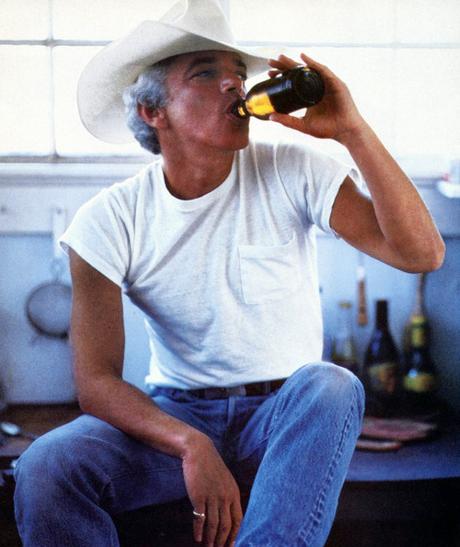

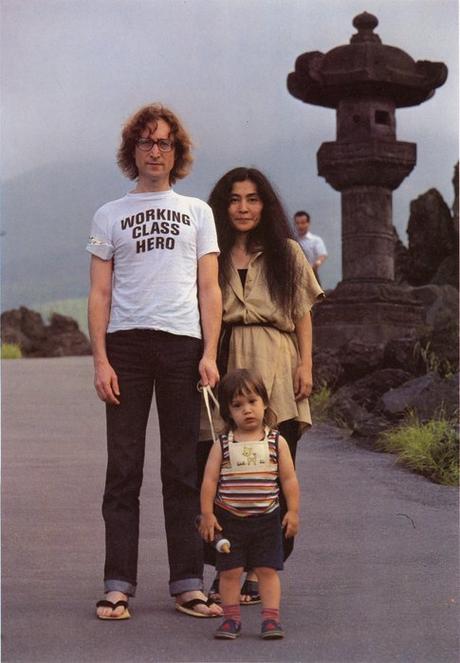

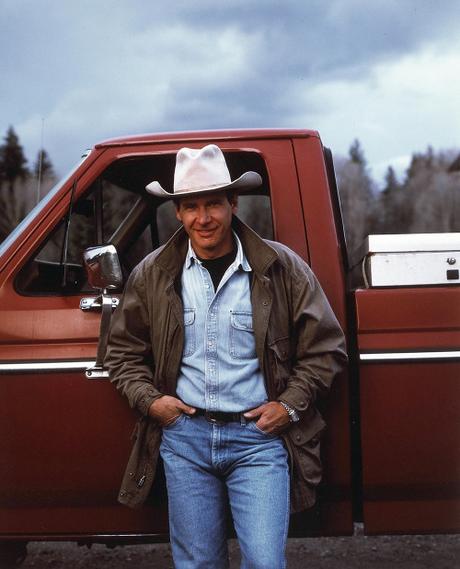

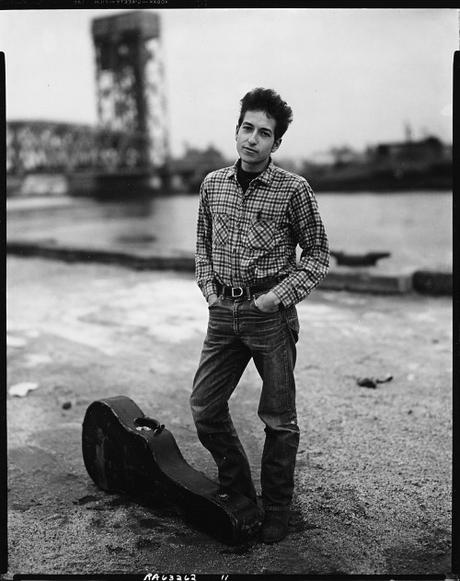

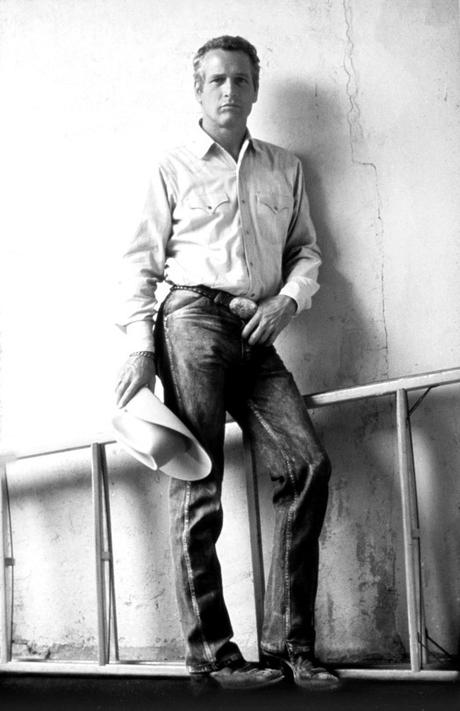

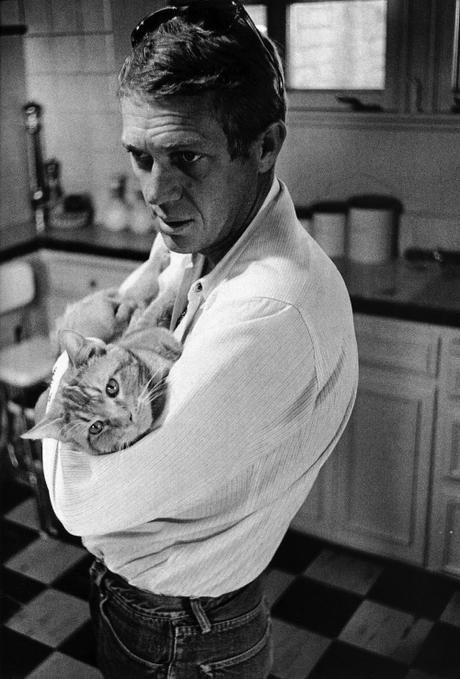

If there’s such a thing as honesty in clothing, jeans are the most honest things you can wear. More than just a garment, jeans are a symbol of a mythological America. They’re the standard equipment of gold miners and cowboys, young rebels and counterculture types. Ownership shows the wearer sees himself as part of a new, liberated society – one that celebrates merit over heredity, individuality over conformity. At the same time, jeans represent a traditional sense of masculinity and the integrity of the working man. Jeans are classic not just because they’re cheap and durable, but because they symbolize a life that millions of people see as enviable, even noble.

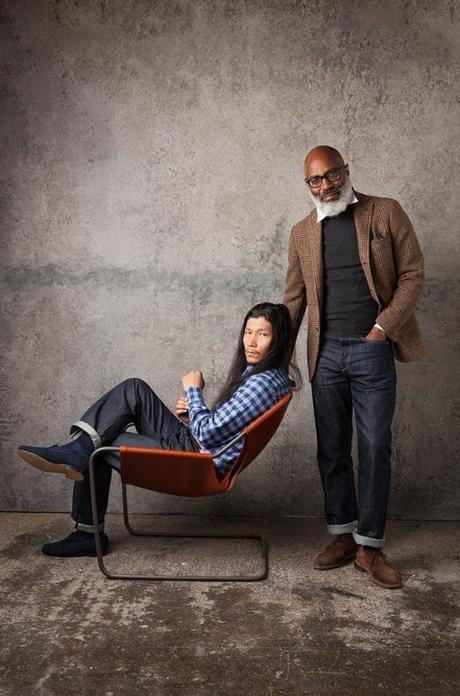

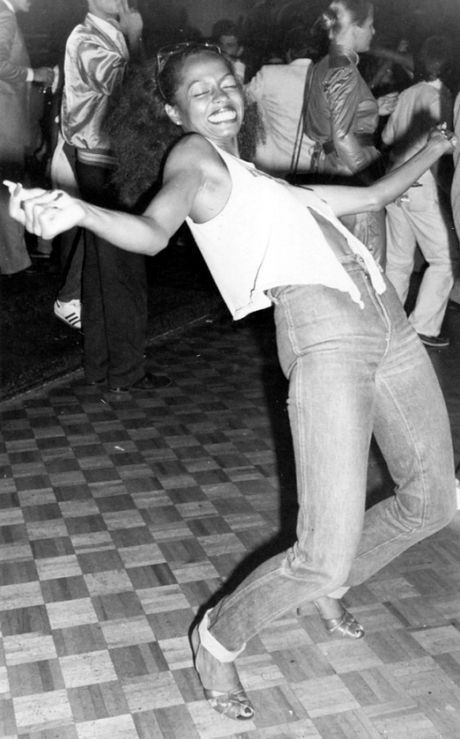

Today’s denim, however, only has a surface-level connection with the past. Jeans are still mostly five-pocketed, riveted, and made with overlock stitching, but they come in a million styles – relaxed or slim-tapered, pre-washed or pre-torn, pure cotton or stretch blend. And production has scaled up to unimaginable levels. The average American consumer buys four new pairs per year. We love jeans because of what they symbolize – hard nosed, working class values – but our consumer behavior tells a different story. Like cashmere sweaters, today’s jeans are treated as semi-disposable items.

The only thing that hasn’t changed is their color. Most jeans, like the ones made nearly 200 years ago, are indigo blue. Much of this dyeing process today, however, is done in Xintang, China, otherwise known as the world’s denim capital.

Xintang is just one of China’s 133 textile manufacturing towns, but it produces the bulk of the country’s denim – about 300 million articles per year, or roughly one in three sold globally. The denim industry here employs about a quarter million of the city’s residents, and has played an important role in lifting Chinese people out of poverty.

At the same time, the "world’s factory floor” has become a dumping ground for debris and waste. In the new documentary RiverBlue, which looks at what the fashion industry is doing to the environment, there’s a scene where dark, frothy wastewater can be seen rushing out of a dye facility, spilling into the surrounding waterways and turning them blue. Supposedly, the land is so bad here, property owners can’t even give homes away. An excerpt from an article at China Dialogue about the matter:

The water in the East River in Xintang has turned blue and smells strange. Under the hot sun, a local man, Dong Yaoming (not his real name), points at a map and says, “This stretch [of pollution] is definitely caused by the bleach factory. Only those factories which dye denim emit such filthy water. They spill the water from dyeing straight into the East River.” Sixteen years ago he would go swimming with his girlfriend in the East River. “But now, I wouldn’t if you paid me.” […]

Xintang’s first dye mill was opened in Dadun Village. It polluted the river and local people were furious. From 2006 they started to put Xintang under some sort of government control and gradually began moving denim washing and dyeing plants to an environmental industrial park in Xizhou Village on the west side of town.

There is clearly nothing “environmental’ about this environmental industrial park. Its main roads are noisy with the roar of boilers, the air stinks of sulfur and ditches are full of dark blue water. Trees along the road have strips of blue cloth hanging from them, the dust in the roads is light blue. The water in all the streams in the area apart from one is black and stinking and the White River is the worst; the slow flowing water is as black as Chinese ink.

Most of this waste comes from the distressing process, where jeans are washed in order to make them look fashionably worn-in, but a bit also comes from the bleaching and dyeing processes required to transform plain white yarns into blue ones. In his Latin description of the Gallic Wars, Julius Caesar wrote “se Britanni vitro inficiunt,” which is widely translated to mean that the Britons dyed themselves with woad, an early form of indigo. Historians question whether this was really accurate, however, since woad isn’t a very good dye for people – it’s caustic and irritates the skin.

It’s also no a very good dye for fabrics. Plant-derived indigo, which includes woad (Isatis tinctoria), doesn’t dissolve easily in water. So it has to undergo several chemical treatments, some involving toxic materials, so that it’s water-soluble and can bind to yarns. Natural indigo, for example, has to be made into "white indigo” (leuco-indigo). When you dip a piece of fabric into this dyebath, then remove it, the white indigo combines with oxygen and slowly transforms into its insoluble, intense indigo color – first coming out green, then becoming blue.

The waste matter left after extracting indigo, however, can leave workers with some serious health problems. During the 19th century, the plight of indigo dyers in Cockermouth, England so moved William Wordsworth that he wrote the following lines in his autobiographical poem, “The Prelude:”

Doubtless, I should have then made common cause

With some who perished; haply perished too

A poor mistaken and bewildered offering

Unknown to those bare souls of miller blue

Today’s jeans are mostly made with synthetic dyes, not natural ones, because of the need to scale production. However, the process isn’t too dissimilar. Since indigo still has a hard time binding onto yarns, it needs a potent bleaching agent – and, even then, it doesn’t bind that well. This is what allows blue jeans to take on those beautifully streaky fades. As the surface layer of the indigo yarns abrade, they reveal their white core.

At the same time, those bleaching agents pollute the environment. The textile industry is pumping out nauseating amounts of dangerous dye waste every year, which isn’t just hazardous for human health, but also darkens river water so flora and fauna are starved of sunlight. The World Bank estimates almost 20% of industrial water pollution comes from textile dyeing and treatment. A couple of years ago, Jim Yardley of The New York Times reported a similar problem happening with the dyeing facilities in Bangladesh:

On the worst days, the toxic stench wafting through the Genda Government Primary School is almost suffocating. Teachers struggle to concentrate, as if they were choking on air. Students often become lightheaded and dizzy. A few boys fainted in late April. Another retched in class.

The odor rises off the polluted canal — behind the schoolhouse — where nearby factories dump their wastewater. Most of the factories are garment operations, textile mills and dyeing plants in the supply chain that exports clothing to Europe and the United States. Students can see what colors are in fashion by looking at the canal.

A few weeks ago, I talked to Avery Trufelman about her six-part clothing podcast series, titled Articles of Interest (which is a must listen, by the way). When I asked what she left out, but wish she could have included, she paused for a moment and then said: “there was so much we had to cut for the blue jeans episode. We visited this small cotton farm run by an incredible woman named Sally Fox. She’s a pioneer in naturally colored cotton. Not many people know this, but cotton doesn’t have to be white. It can be a variety of natural, earthy colors – green, red, brown, and beige – which can save a tremendous amount of waste and water in the dyeing process.”

Farmers have been growing naturally colored cotton for nearly 2,000 years, but uniform white varieties have been favored since the industrial revolution since they allow spinners to produce cheaper yarns. Supposedly, back when cotton was “king” of the American south, plantation owners grew white cotton on their fields, but allowed slaves to grow colored cotton on their own. This is because colored cotton isn’t commercially viable. It’s a shorter staple fiber, which means it’s hard to spin into useable thread. And since it has a natural base color, it’s not very good for dyeing into other hues. So, the commercial side of these plantations were filled with fields of white cotton, while small patches of colored cotton were allowed to be kept near slave quarters. “It’s weird to me that the whiteness of cotton was reflected in the social structure,” says Trufelman.

Throughout the last two hundred years, naturally colored cotton has been mostly cultivated as a last-ditch effort to meet a need. When there were dye shortages during the Second World War, for example, the US government encouraged farmers to grow brown and green cotton. But since the shorter fibers were less durable and required hand spinning, they fell out of favor again after the war.

In the early 1980s, the US Department of Agriculture made another push and gave cotton breeders brown cotton seeds. Sally Fox was one of the people who received such bags. And over the last forty years, she’s turned that initial bag of heirloom seeds into more commercially viable, long-staple fibers. Her company, Vreseis Limited, earned nearly $10 million in business during the ‘90s. She supplied naturally colored cottons in earthy tones of red, green, and brown to major companies such as Levi’s, Land’s End, and L.L. Bean. However, as trade has become more globalized, spinning mills have since shifted to South America and Southeast Asia, where white cotton continues to dominate. You can still visit Fox’s farm in Northern California, however. Trufelman tells me, when she visited, she was able to sift through some of the company’s shade cards, where each color has taken about ten years to develop.

It’s hard to say definitively what would be the environmental impact of switching to naturally colored cotton. Critics note that conventional cotton varieties have a higher yield, meaning a single plant will produce more fiber than its organic, naturally colored counterpart (largely because they haven’t been genetically modified). According to Cotton Inc., a research group that serves the cotton industry, it takes 290 gallons of water to grow enough conventional, high-yield cotton to produce a single t-shirt. To grow the same amount using organic cotton requires 660 gallons of water.

All this may be moot, however. If anyone has ever doubted that color in fashion should be treated like social language, and not abstracted color theory, think of how we choose our jeans. Black jeans are edgy and moody, while white jeans are a bit preppy. Blue is the classic color of denim because it says something about the garment’s meaning. “It’s such as small fashion decision, but it’s having a tremendous impact,” says Trufelman. “If we could just let go of this idea that jeans have to be blue – like, if there could be green jeans and brown jeans – we could save so much water globally.”

So ,what’s a more environmentally conscious shopper to do if he’s not willing to give up his blue jeans? Some years ago, Michael Pollen, author of In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto, gave this succinct summation of how he thinks people should eat: "Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.“ The idea is so simple you’d think it hardly needs to be stated, but in an overcrowded marketplace full of fad diets and pseudo-science solutions, it’s deserves to be reiterated.

A similar ethos can be applied to fashion: buy less, buy better. Wear what you own until its end-of-life, then repair and wear some more. Avoid fast fashion like the plague and don’t buy things that will just wind-up in a landfill (no one wants a used H&M shirt, while better-made clothes can at least be resold and passed on). Also, wash your clothes only when necessary. Your laundry machine uses a lot of water and energy as well.